Akin Iyapo

Character: Akin Iyapo

Source Text: Octavia E. Butler, Adulthood Rites (1988)

Entry Author: Ilana Yoneshige

Throughout Adulthood Rites there are predictions made about the behavior of Humans, as well as the character development of Akin. Lilith, his Human mother, worries that the resistors will hate Akin more than the other construct children because he is male. She says to Nikanj, her ooloi mate, “They will! He isn’t human. Un-Human women are offensive to them, but they don’t usually try to hurt them, and they do sleep with them – like a racist sleeping with racially different women. But Akin…they’ll see him as a threat. Hell, he is a threat. He’s one of their replacements” (10). This quote is a statement that reflects the real world attitude towards males of another race.

Akin is kidnapped in a raid; the resistors, though they refuse to live alongside the Oankali, decide to kidnap many of the construct children out of a desperation to have children among them. Akin is taken to Phoenix where he learns more about his Human ancestry. Tate and Gabe buy him from the raiders and care for him. In Phoenix, Akin learns that the Humans try to humanize the construct children. Several of the people plot to remove the sensory head tentacles of two of the female construct children; a cosmetic surgery that would be lethal to them. Although Akin recognizes and agrees with the Oankali belief that the Humans, if left alone, would revert to their hierarchical tendencies and self-destruct again, the Human part of him understood the need for freedom and choice. When Akin is rescued and returns to Lo, he and the other construct children convince the Oankali to transform Mars into an inhabitable planet.

Akin is special because he is able to identify with both his Oankali and Human ancestry more than any of the other construct children. He chooses to support both the gene trading between the Oankali and Humans as well as the Mars settlement because he is a mixed race child.

Roxy

Character: Roxanna

Source Text: Twain, Mark, and R. D. Gooder. Pudd’nhead Wilson and Other Tales. Oxford [England: Oxford UP, 1992. Print.

Entry Author: Shalyn Hopley

Roxanna, more often referred to as Roxy, is one-sixteenth black. Roxy is one of two mixed race characters at the center of Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson. Roxy is a slave, but “to all intents and purposes Roxy was as white as anybody, but her one sixteenth of her which was black outvoted the other fifteen parts and made her a negro,” (Twain 8). She is described as looking as white, but her mannerisms are fitting of a black slave. Roxy is the caretaker for two boys, her own son and the white son of her masters. Both children are indistinguishable without clothing by the master of the house. Roxy’s actions regarding the children are central to the plot of Twain’s novella. In a fit of panic about the possibility of her own child being sold “down the river”, Roxy decides to kill herself and her child. Before carrying out the act, she dressed both herself and her son in their finest clothing. Upon seeing her child, she realizes she can switch the children, which she does, and pass her son off as the master. The children, Tom, the master’s son, and Chambers, her own child, are given each other identities in infancy and it is this action that carries the novel forward.

Roxy is a complicated character, drawn complexly at the center of the complications of an illogical system of blood. Roxy eventually is freed by her master Driscoll and works her own way on a river boat. She watches Tom, who was originally Chambers, grow into a spoiled child who scorns her. She reveals to Tom his heritage, and they together concoct schemes, yet she is still betrayed by Tom who sells her back into slavery down the river. While Roxy’s actions are revolutionary and challenge the status quo on face value, they ultimately are problematic. Firstly her actions are not openly defiant, nor are they the most ethical. Her switch is like an “eye for an eye,” a child for a child. She condemns Chambers to a life of slavery and the possibility of being sold down the river. While she subverts the system by having a “black” child in the position of master and a white child in the position of slave, she has not found a means to truly affect change. She has made one individual change while the system remains intact. Additionally, her actions are ultimately righted with disastrous consequences for all involved. Tom is condemned to slavery, sold to the men to whom he owed gambling debts; Chambers rises into a class he is unable to fit into due to his upbringing; Roxy’s heart was broken by the misfortunes that have befallen her son and the child she condemned to slavery. Roxy may try to challenge the status quo in Dawson’s Landing but she is not successful, her actions producing no victories, the system of blood continued.

Magiere

Character: Magiere

Source Text: Gene Roddenberry, Hendee, Barb, and J. C. Hendee. Dhampir. New York: Roc, 2003. Print.

Entry Author: Peter Murphy

“In the years before Leesil, all she had was loneliness, which turned to hardness, which turned to cold hatred of anyone superstitious. A mother she’d never known was long dead, and her father had abandoned her to a life among cruel peasants who punished her for being spawned by him. Why would she want to remember such things? Why would she want to look back? There was nothing worth concern in the past (Dhampir 214).”

Magiere is one of three protagonists in a low magic, low technology fantasy setting. She is a mix of vampire, a form of noble dead, and human in a world where humans and elves are the primary inhabitants. Other races exist or have existed, but operate outside the zone of society covered by the books.Her primary occupation is vampire hunting, an activity for which she was effectively bred. In the presence of vampires, she gains superhuman speed and strength as well as a sort of bloodlust. Prior to the start of the series, she works as a charlatan by pretending to slay vampires for superstitious villagers. She meets Leesil, a half-elf, and is inspired to journey with him, but rapidly finds kinship with him because he is similarly isolated from society. The two, along with a fey dog named Chap, slay vampires while searching for a greater understanding of their identities. Magiere, later in the series, finds that she is constructed from a ritual necessary to combine the living and dead.

Later, among the elves, she experiences considerable distrust and loathing for being a dhampir; the world is only now recovering from some apocalyptic event resulting from hordes of undead. With her vampiric heritage, Magiere represents to the elves, who still remember the danger posed by undead and especially “noble dead” who are capable of thought, the ultimate form of miscegenation. Magiere is frequently confronted by what it means to have her legacy and is required to grapple with the idea of part of her being parasitic. In the novel, there is little to be redeemed by most undead. The vampires she faces are required to kill people and obey the orders of their master, the individual who conscripted them into unlife, but many feel no moral complications from their life.

Magiere is noble, certainly, and loyal to her friends, but is not the typical adventurer. All she wants to do is settle down, but she is dragged to adventure by her urgent need for self-knowledge and her loyalty to Leesil. She is forward thinking, but compelled by the past.

Thomas Chambers

Character: Thomas Driscoll

Source Text: Twain, Mark and Sidney E. Berger. Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins: Authoritative Texts, Textual Introduction and Tables of Variants, Criticism. New York: Norton, 2005.

Entry Author: Jonah Beukman

Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson satirizes a culture in which titles and nobility hold significant value. The dominant culture in the novel, which is one of affluence and “whiteness”, is proven to be superficial and false. Twain indicts a society that equates whiteness with nobility and blackness with bad character and complicates this notion with Thomas Driscoll, who is mixed race; his identity is not fixed and his malevolence as a character cannot be linked to biological determinism. Both Tom and his brother Chambers are one-thirtysecond white, yet Chambers is made out to be a benevolent character, whereas Tom is seen as wicked. His role in the social and societal settings of the novel is that of an antagonist, seen mostly in the act of selling his mother, Roxana, down the river as a slave. Yet he is not entirely unsympathetic, and Mark Twain complicates the notion of Tom’s “wicked” identity being due to his race. Tom’s identity as a mixed-race character is put into question in the following passage:

It was the “nigger” in him asserting its humility, and [Tom] blushed and was abashed. And the “nigger” in him was surprised when the white friend put out his hand for a shake

with him. He found the “nigger” in him involuntarily giving the road, on the sidewalk, to the white rowdy and loafer. When Rowena, the dearest thing his heart knew, invited him

in, the “nigger” in him made an embarrassed excuse and was afraid to enter and sit with the dread white folks on equal terms. The “nigger” in him went shrinking and skulking here and there and yonder, and fancying it saw suspicion in all faces, tones, and gestures (49).

Mark Twain puts into question several dichotomies here which relate to mixed-race and mixed identity. He satirizes the notion that being black is synonymous with being meek and unassertive, while complicating Tom’s actions as a character. “The ‘nigger’ in Tom” refuses to acknowledge white individuals. He “involuntarily gives the road” to white individuals who are not necessarily worthy of his respect as an act of deference. The word involuntarily suggests that at least part of Tom’s identity is inherent regardless of race, despite Twain’s false and superficial claim that “blackness” is on par with being evil. Tom also refuses to accept Rowena, “the dearest thing [that] his heart knew” inside, indicating that his black identity satirically informs sexual meekness as well. Tom goes “shrinking and skulking here and there and yonder” as a further indicator of Twain’s indictment of the waywardness of Black individuals. Black individuals may be wayward, according to Twain, but Tom’s mixed race and his acknowledgment of the dual identities that comes from both his “white” and “black” identities make him a character that defies the status quo. Twain himself defies the status quo as an author here through Tom’s duality in identity, which represents a prototype in post-structuralist thought

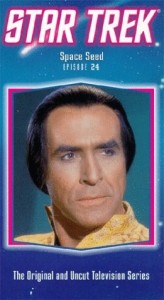

Khan Noonien Singh

Source Text: “Space Seed.” Star Trek: The Original Series. Writ. Gene L. Coon and Carey Wilber. Dir. Mark Daniels. NBC. 1967.

Entry Author: Emma Baker