James Fulton

“I always knew they didn’t have the same daddy, but I didn’t know his (Fulton) was a white man.”

“Who else knows that Fulton was colored?”

“But he wasn’t who he was. He passed for white. He was colored.”

“Fulton’s hatred of himself and his lie of whiteness”

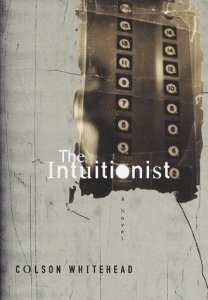

In Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist, James Fulton is the elusive, sought after inventor of the Intuitionist school of thought and author of four renowned volumes on theoretical transport. Although he passes away prior to the start of the novel, his legacy leaves a haunting omniscience that leaves much to be uncovered and explored as the story unfolds. For protagonist Lila Mae, the first black female elevator operator praised for her keen intuiting abilities, the struggle to discover the man behind James Fulton and his confidential theory on the “black box” becomes a testament to Lila Mae’s own self discovery.

As a pioneer of intuitionist ideology Fulton’s presence in the novel is largely indirect and unobtrusive, seeping through the text in brief interludes during Lila’s moments of deep contemplation. Throughout the narrative, excerpts from Fulton’s “Theoretical Elevators” are caught between chapters, and introduce certain sections of the book, though most indiscreetly. Like Lila Mae, we as readers attempt to uncover the mystery behind Fulton’s largely allegorical concepts such as the “thin man convention” and the “Occupant’s Fallacy” (38). At first glance, Fulton’s ideology seems highly probably in conjunction with dry, repetitious elevator terminology. In fact, the fallacy of the thin or obese man who is not considered for the standard occupancy of a residential elevator of 12 passengers seems highly believable, however, we as readers fail to notice the undeniable parallel between the “thin man convention” and Fulton’s secret analogies hidden within the text.

Though we are given little information on the character or background of Fulton, aside from the acclaimed excerpts strewn about the novel, his message is far from audible. For Fulton, the black box is “the second elevation” in which there is “no need for safety devices because there is only up…” (182), which is, in its entirety, the perfect ascension is a gateway towards a classless society unconstrained by racial boundaries. However, Lila Mae’s discovery of Fulton’s mixed racial background towards the novel’s conclusion lends contextual significance to Fulton’s claim for vertical uplift. In fact, Fulton’s identity as a figure of mixed racial inheritance, the combination of a white father and black mother, completely alters the arrangement of the fixed, pre-existing social and political backdrop of the novel. Prior to Lila Mae’s discovery, The Intuitionist’s world of elevator inspection is a metaphorical representation for a society hindered by social division, each group designated and confined to their own “boxes”. The tension between the Empiricists, a selective group of dominant white alpha males who dedicate their professions to rationality and reason, and the intuitionists, the seemingly inferior competitor who treats inspection with passion and gut feeling, elicits a symbolic comparison to a more palpable reality of racial hierarchical divisions.

Fulton’s hidden identity has allowed him to pass in a society that if revealed, would have never allowed him access or authorship of such a highly revered position. Because he looks white, he passes as someone with unquestionable agency in the field of Intuitionism, and one that he uses in efforts to reimagine a system already established. Concealed by texts administered for Intuitionist training, Fulton’s theories were a reminder of “the hatred of the corrupt order of [the] world, the keen longing for the next one, its next rules.” (232) As Lila Mae is forced to interpret what she terms, “a big joke,” “the perfect liar that world made him, mouthing a supreme fiction the world accepted as truth,” the black box becomes less of an obtainable object. Rather, it imagines a means for a presently unimaginable society, a place that would have accepted Fulton no matter what color he was to the rest of the world.