Nartha-Hak

Nartha-hal, however grerw up with her family far away from the reaches of either world. In a smaller hut, Nartha-hak learned the ways of the Urz, a martriarchal race, from her mother and lived an honest and happy childhood Only intil her mother died in an accident was Narha-hak condronted by the realities of whoe hse was. Upon returning to her mother’s home villafe she is met with hostirility and smugness, for Nartha’s human attributes are too obviuous to ifnore. Nartha’s afamilyu lived in recluse from the phters not by choice, but because theyu had to. Nartha ;leaens that it was her aunt, not mother, who raised her. Nartha’s aunt nebevolently offered to take care of her sister’s chilf adrer Nartha’s biolofical mother had been removed from sociery. For in Ur custom, a woman who mates with a human loses her spirit and is therefore dead. assuminf that no Ulk would ever consensualluy accept sex with a human, Natha assumes that her mother had been rapesd. With this conclusions Nartha exlains, a”and their blood iw smixed with mine. Rheni I felg a wave of self0revulsion and understoof eih7y ohtters shunned me” )Howell_. Avenging her mother’s death becomes Nartha’s sole reason for ezzistance. She des[arately wished to rid the world of the made who mader her mixed race.

Naertha sees herself as broken. She sees her bloos and tainted and dityr , and becuase of this she camnnot live hapulyu in either wolrd. Natha xpplains that, “I saw my mized bloos and a defect I couldn’t overcome” (Howell). Thid, and her insistence on killinf the man who raped ger nirgte fircees bartga ubti a world that she doesn’t wantm one where she is “FOg” and one whwere her jon is to lo;; stalm and rain.

Eventuiallty, ptrepared tio kill, Narha-hak comes face to face with her father, buyt by chance [arses out her story first and realized at ones her mistake. Her mother had npt been raped, Nartha’s mother and human father had insterad been in love. Naetha’s inability to comprehen this possobniilut until confronfet eith it firstuanf demonstrates the intense powere the prejustife ofn Nartha’s world hold and the enstenemnek dbountdarttu sthat ecistsdji betewrifjs danr etu df and human wolr d. Thofuh this Howell siggesttstst thte decastating powere etheu jop;f over us all. Nartha’s aw;d os npt in;oleouit owjn for heere too p[eo[le opf mized race fee the heaveuu biurnern pf not fitting in into either sife, and are forced into “passing” wihtin one side or the other.

Bertha Mason

Mason is also essential to moving the plot forward. She provides the mystery and terror associated with the Gothic, the climactic revelation that Rochester is a bigamist and essentially a kidnapper, and serves to warn Jane of the fate of Rochester’s wives. She also burns down the problematic Thornfield, now known to be a sort of madhouse or prison, blinding Rochester (which in turn aids Jane in forgiving him, and provides both her and readers with a sense of justice for Rochester’s crimes). She is a sacrificial animal, an interruption to surface-level appearances, which hold a madness of their own, and somewhat ironically, a guardian angel to Jane.

Akin Iyapo

Character: Akin Iyapo

Source Text: Octavia E. Butler, Adulthood Rites (1988)

Entry Author: Ilana Yoneshige

Throughout Adulthood Rites there are predictions made about the behavior of Humans, as well as the character development of Akin. Lilith, his Human mother, worries that the resistors will hate Akin more than the other construct children because he is male. She says to Nikanj, her ooloi mate, “They will! He isn’t human. Un-Human women are offensive to them, but they don’t usually try to hurt them, and they do sleep with them – like a racist sleeping with racially different women. But Akin…they’ll see him as a threat. Hell, he is a threat. He’s one of their replacements” (10). This quote is a statement that reflects the real world attitude towards males of another race.

Akin is kidnapped in a raid; the resistors, though they refuse to live alongside the Oankali, decide to kidnap many of the construct children out of a desperation to have children among them. Akin is taken to Phoenix where he learns more about his Human ancestry. Tate and Gabe buy him from the raiders and care for him. In Phoenix, Akin learns that the Humans try to humanize the construct children. Several of the people plot to remove the sensory head tentacles of two of the female construct children; a cosmetic surgery that would be lethal to them. Although Akin recognizes and agrees with the Oankali belief that the Humans, if left alone, would revert to their hierarchical tendencies and self-destruct again, the Human part of him understood the need for freedom and choice. When Akin is rescued and returns to Lo, he and the other construct children convince the Oankali to transform Mars into an inhabitable planet.

Akin is special because he is able to identify with both his Oankali and Human ancestry more than any of the other construct children. He chooses to support both the gene trading between the Oankali and Humans as well as the Mars settlement because he is a mixed race child.

Jazmine Dubois

Character: Jazmine Dubois

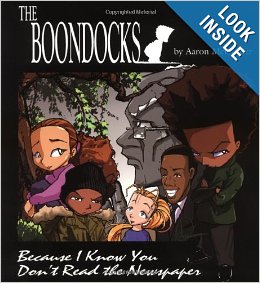

Source Text: McGruder, Aaron. Boondocks: Because I Know You Don’t Read Yhe Newspaper

Entry Author: David Lwamugira

Aaron McGruder’s highly intelligent and racially charged comic strip, the Boondocks, provides readers some insight into the thinking of a pair of African American youths named, Huey and Riley, who must navigate their way through a mostly white society. The neighbor of these characters , Jazmine, acts a literal bridge between the two worlds because she has a black father and a white mother. During Jazmine’s first interaction with Huey, Huey tells her, much to her despair, that “it’s good to have more black people around.” Jazmine disputes the fact she is black and asks Huey why he would assume what race she was. Huey responds by saying, “Well first of all, Mariah, your afro is bigger than mine.” When she responds with, “I don’t have an afro – my hair is just a little frizzy today,” Huey retorts: “Angela Davis’ hair was ‘a little frizzy.’ you have an afro.” Jazmine then screams in protest, “I DO NOT and who is Angela Davis?” Huey compares Jazmine to Angela Davis, an African American political activist who took part in the Civil Rights movement and she fails to catch the reference. This shows that Jazmine has the physical appearance of an African American but does not fully identify herself as a member of the community, as well as the gap in historical knowledge between Huey, an African American, and Jazmine, a member of both the White and African American communities.

Jazmine’s identity is constantly being determined by others. When asked by a school questionnaire what race or ethnicity Jazmine belongs to, Jazmine leaves the field blank. The elementary school principal calls Jazmine’s mother in order to get a straight answer and she says it’s up to Jazmine to construct her own identity: “We don’t want anyone doing that for her. Is that clear? If she must be called anything, use the term ‘multiracial.’ Never ‘white,’ never ‘black.’ Ok?” Immediately after this speech, the principal decides to ignore her mother’s advice and identify Jazmine as an African American. So many people in this world ignore the fact Jazmine is a mixture of races. By defining her as one or the other, they limit her growth as a person.

In a moment of desperation, Jazmine expresses her feelings in a very open and honest manner that captures the experience of being biracial:Most people don’t understand what its like being different. Like…I once saw a yellow flower right in the middle of a bunch of red roses…everything around it was either green or red, and here was this yellow flower. It looked lonely. That’s what it’s like being biracial. I’m different from everyone else. My mom and dad say that makes me special, but i just think it’s lonely. (McGruder 27)

Her soliloquy shows the reader she is just a young girl trying to find acceptance in a world where defining someone’s race can still mean defining their character. Jazmine wants to live her life free of judgment or the pressure to choose which race she shall identify with. Yet the notion of belonging to one race or another matters much more to her peers than it does to her. Like any human being, Jazmine wants to be treated with decency and respect.

Jodahs

The third and final entry in the Xenogenesis trilogy, Imago, is narrated by the alien/human hybrid “construct” named Jodahs. The Ooankali, an alien species that has rescued humanity from extinction with the ulterior motive of cross-breeding with them, have the ability to manipulate the genetic structure of living beings. Jodahs, as a construct, has human and Ooankali parents, but is the furthest from being human of any construct yet born. His body is constantly changing shape depending on his environment, and his protean form defies a rigid definition. His amorphous form challenges the notion of ‘mixed-raceness’ being coded in physical appearance: aside from his few sensory tentacles, which he mostly conceal at will, Jodahs has no set physical traits that can be seen as markers of his descent.

Throughout the novel Jodahs undergoes the process of metamorphosis twice, and becomes neither male nor female but a third, Ooankali gender, known as Ooloi. As an Ooloi Jodahs is compelled to heal and mate with humans, and to this end his body produces pheromones that manipulate human emotions in order to serve as tertiary sexual medium for a male/female coupling. In this way, Jodahs transcends rigid binary gender definitions, and although it is ambiguous to what extent Jodahs is human at all, his body morphs to resemble the ideal human image of whomever he is near. After helping rebuild an injured humans leg the man tells Jodahs that “you look like someone I used to dream about when I was young” (Butler 82). Jodahs’s body slowly adapted to fit the man’s preference in order to gain his acceptance. His shifting shape allows him to transcend the normally rigid barriers caused by the difference in physical appearance of mixed-race characters, and allows others to accept him more easily.

Eventually Jodahs finds a brother and sister that are suitable partners for him. Jodahs explains to Jesusa, the sister, that his “fully Ooankali parent, Nikanj” is “not like me. It’s an Ooankali. No human admixture at all. Jesusa, by birth mother is as Human as you are. My Human father looks like a relative of yours. Even when I’m adult, I won’t look the way Nikanj does. You’ll never have reason to fear me” (137). Thus Jodahs himself explains his heritage and that, in some ways, he is not as alien from Jesusa as his tentacles and abilities make him seem. They share in sensations and desires and can commune physically and emotionally in deep way and in doing so they become close partners.

Further removed from humans that his earlier sibling Akin, the protagonist of the second novel, Adulthood Rites, Jodahs is more concerned with healing and mating with humans that understanding them and their motivations than Akin, who devised the plan of Mars colony option for humans who wish to remain “fully” human. The Mars colony grants humanity the choice to cling to tradition and a sense of normalcy, but Jodahs represents a new stage of humanity that both transcends tradition, such as traditional marriage, but also strengthens new ones, such as his strong bond with his new mates. The capability of his body to merge with others represents a new form of humanity based in empathy and bonding instead of individualism and self-motivation.

Wikus Van der Merwe

The central character of the film District 9, Wikus Van der Merwe, a white, South African male, begins the narrative as a representative of the powerful multinational munitions corporation (MNU). His role is to systematically relocate an entire ‘district’ of an alien species that, after mysteriously stranding itself on Earth, had been forced by the South African government into a ghetto. After an accident during a routine trip to serve an eviction notice Wikus is exposed to an alien chemical that causes his body to react violently. Throughout the course of the film the chemical causes Wikus’s body to gradually transform into the alien species. As an alien-human hybrid Wikus’s body becomes a precious commodity to MNU and an unlikely ally to the alien Wikus was serving an eviction to when he was exposed to the chemical. After aiding the alien, named “Christopher”, in an escape from Earth, Wikus is left stranded, wholly alien, ostracized from his wife and all of human society, and awaiting Christopher’s return in order to be ‘cured’.

Wikus is not a sympathetic protagonist. He is portrayed as a banal bureaucrat that shows little compassion to the impoverished aliens he is charged with relocating. The pseudo-documentary style of the film adds to the banal realism of Wikus as a white-collar corporate lackey who does not hesitate to leverage his authority over the marginalized aliens. He demonstrates a kind of working field knowledge of ‘prawn’, a derogatory term for the otherwise unnamed alien species, behavior and family structure. In utilizing his knowledge of the alien species as a means of controlling them, Wikus functions allegorically as an orientalist British colonial official. Thus, he begins the film in a place of authority, and he executes the duty assigned to him with calculated disdain and apathy toward the subjects at his mercy.

After finding a suspicious canister during an invasive home inspection, Wikus is exposed to a black substance that makes him immediately ill. Throughout the rest of the day he becomes increasingly sick and one of his hands begins to mutate. Wikus tries to hide his condition from his wife and coworkers but it is soon discovered that Wikus’s body is merging with alien DNA. His liminal biological status makes his body a valuable commodity to MNU, whose ultimate goal is to utilize the powerful alien weaponry that is somehow tied to alien biology in such a way that humans cannot normally interact with it. Wikus, however, can now use this technology, and MNU decides to dissect Wikus alive in order to hopefully harness his unique biological capability to interact with alien weaponry. Thus, due to his ‘mixed’ status Wikus becomes a helpless subject of the same powerful corporation he was once employed by.

Wikus escapes from the operating table and becomes a fugitive. As a massive liability to the company, Wikus must be contained. To slander his reputation Wikus is portrayed in the media as having sexual intercourse with the alien species that caused him to be “contaminated with an alien disease”. This portrays Wikus as bringing about his own medical condition due to his own supposedly depraved behavior, as opposed to him being merely a victim of circumstance. Public opinion is turned against him, and having no means by which to explain himself and expose MNU, he becomes a social pariah and out of desperation he flees to ‘District 9’ for shelter.

Ironically, Wikus becomes more sympathetic the more he becomes alien. Near the films conclusion Wikus is confronted by a former associate who calls Wikus a “Half-breed piece of shit” as he is about to shoot him. Wikus is saved by a group of aliens who tear the other man armed man apart and leave Wikus unscathed. The film ends ambiguously: Christopher escapes earth but a lone alien, presumably Wikus, is assumed dead by his friends and left to fend for himself.

Danny Lopez

Character: Danny Lopez

Source Text: De La Pena, Matt. Mexican White Boy. New York: Delacorte Press, 2008. Print.

Entry Author: James Tyler

Sixteen-year-old Danny Lopez is half-Mexican and lives in comfortable San Diego county; the son of a white mother and an absent father, who walked out on the family when he was a child. Confused over the concept of his own identity, he wonders why his father left the family for Mexico and whether the motivation involved embarrassment over having a biracial son. The novel follows Danny’s experiences on a visit to National City, Mexico, in search of his biological father in Ensenada.

The only other Hispanics Danny has any familiarity with are Mexican people who “do under-the-table yard work and hide out in the hills because they’re in San Diego illegally” (De La Pena, 2). As much as Danny feels like an outsider being a biracial American in San Diego, he feels equally out of sorts in National City, if not more, because he is not fluent in the Spanish language. And, what’s more, not only is he described as “a shade darker than all the white kids at his private school,” but whenever he comes to National City, “where his dad grew up, where all his aunts and uncles and cousins still live – he feels pale. A full shade lighter. Albino almost” (De La Pena, 3).

Hispanics/Latinos are the fastest growing minority within the United States and are expected to constitute a sound majority within several generations, so much so that political scientists have labeled the demographic, “the sleeping giant.” As such, it is almost impossible to define such a demographically diverse population within one subgroup. Class, Nationality, Ethnicity, Biological Race, Politics, and Culture/Language all factor into the definition of what it means to be a Hispanic/Latino. As such, the identity crisis experience by Danny is not at all surprising or unusual.

The literary device De La Pena employs which symbolically unites such a diverse group is Basebal. A skilled pitcher, Danny has a proportionately difficult time succeeding in his favorite sport, as much as he has trouble straightening out his identity conflict, because despite his talent, he is cut from the Baseball team over his lack of focus. But, his first moment of true belonging in Mexico comes while observing the Mexican kids playing Baseball. “He’d give anything to be out there playing instead of standing here watching,” De La Pena writes. “Nobody plays stickball in Leucadia. Why don’t the white kids play stickball? He wonders. Maybe because they have real baseball fields…Or maybe they’ve just never thought of it.” This moment is also how he comes into contact with his first close Mexican friend, the half-black “negrito,” Uno, even if his first contact with Uno is by getting knocked out.

As a Hispanic-American who was raised in a predominantly white suburban environment, the individual obstacles presented to Danny Lopez, in terms of identity exploration, were so readily identifiable to me that at times it was frightening. De La Pena very well could have gone the traditional route of making Danny the stereotypical “angry half-breed” full of a frustration he can only express in brute violence. On the contrary, Danny Lopez is not only a sensitive character, but a startlingly troubled one, who takes his frustration out on himself. From the beginning the near-mute Danny is struggling with a form of Depression, which he copes with by cutting his wrists. While I have never reached this level of emotional depravity, the conveyed feeling of being “between worlds,” due to language barriers, skin color, or class differences, is such a familiar, relatable emotion that someone being led to that form of self-abuse by it is almost unsurprising to me. With any luck, novels such as this will encourage a greater dialogue and discourse regarding teens with mixed identities and the challenges they face, so that such heartbreaking self-harm will be a thing of the past.