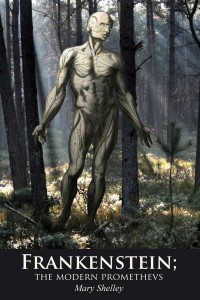

Frankenstein’s Creature

Character: Frankenstein’s Creature

Character: Frankenstein’s Creature

Source Text: Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. New York: Illustrated Editions, 1932. Print.

Entry Author: Claire Tierney

The Doctor reluctantly agrees, yet never follows through on his promise to create a female. The creature is angered and forced to violence, which impels Dr. Frankenstein to devote his life to the destruction of his creation. He fails in his search, and his creature is last seen by the narrator walking into the cold northern tundra, “lost in darkness and distance” (239).

The title’s allusion to Prometheus compares Dr. Frankenstein’s creature to a heroic figure in Greek mythology responsible for providing humanity with fire, a intellectual and progressive achievement. Prometheus is created from clay, an origin not dissimilar to Frankenstein’s patchwork configuration. His punishment is tragic, as he is to be eternally tortured.

Frankenstein fits the trope of the tragic mulatto, never fitting into any culture, forever an outsider in his own world. Frankenstein suffers because no one is like him. No One exists who is the same as him, physically, culturally, or racially. Frankenstein is a gothic novel, acting as mirror to societal fears of of the unknown, and the abject. Just as humanity repeatedly finds the notion of fellow humans that look and sound different to be threatening, so Frankenstein is perceived as a menace.