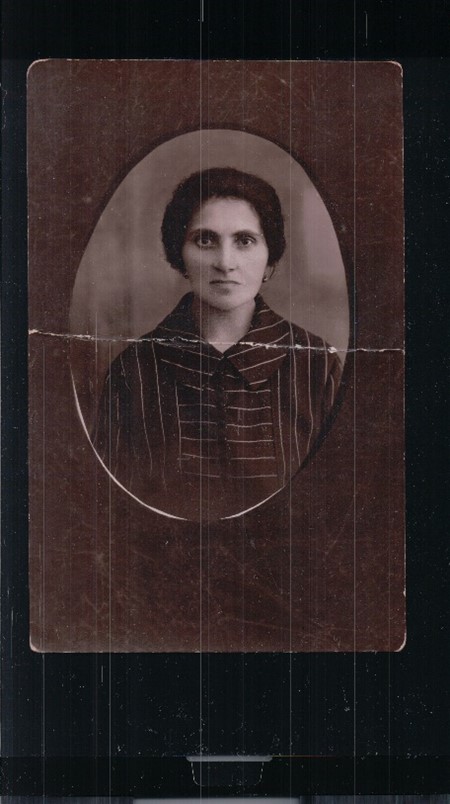

My mother came from poverty and struggle in a shtetl of Poland. Born in 1914 in Lask, a small town near Lodz, she was the youngest of eight children and her father died when she was one year old. That pushed the family into poverty; she often went hungry. They moved to Lodz in search of employment. In that industrial city each sibling went to work in one of the many factories there when they turned 14 years old, and my mother was no exception. As a young adult she joined the communist movement, inspired by the ideas of a better society than the one she experienced. This is how she met my father.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, her political involvement allowed my parents to grasp the threat that Hitler represented for Jewish people. The other family members did not want to think about it, did not believe it. As communists, my parents would be the first target of the Nazi occupiers, a and it was clear that they had to run. As soon as my father recovered from an almost fatal wound he received as a soldier in the Polish Army, they crossed the border to the Soviet Union and became one of the tens of thousands Jewish refugees in Ukraine. Although crossing the border was dangerous, once they were in the Soviet Union, they were safe. They became employed in industry and started making some kind of life for themselves until June of 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. They were refugees again, this time landing in Uzbekistan. Everybody suffered terrible hunger, some people, especially infants, perished from starvation. With all the Stalinist terror and other atrocities that took place within the Soviet Union, I always remind my friends and acquaintances that this was the only country that gave shelter to tens of thousands of Jewish people fleeing the Nazis. This perspective made me rather unpopular in my local temple.

Two years ago, my husband Philip and I traveled through Uzbekistan and I saw these cotton fields where my mother once worked. I also met in a small synagogue in Bukhara, where an old rabbi told me stories about the waves of Jewish refugees from Poland and the German-occupied soviet territories. I am grateful to be able to speak Russian to hear these stories.

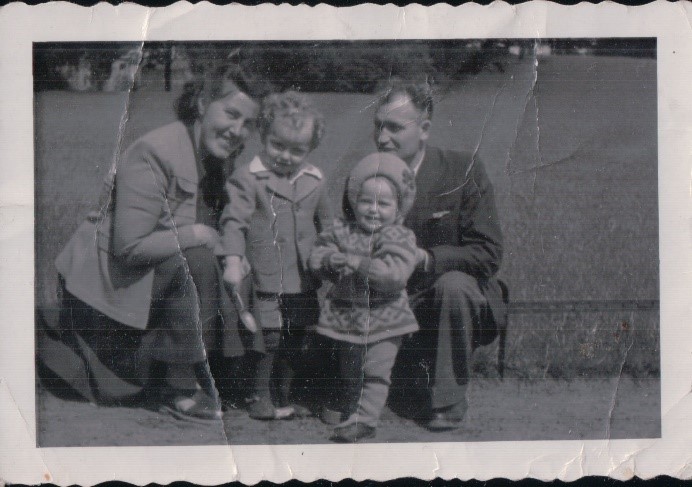

When the war ended my parents repatriated to Poland. They found only death and ruins. They were refugees again, with nothing but clothes on their backs. It is hard to grasp the incredible movements of people in that part of Europe during the first post-war years. Millions of displaced people: by war, by retribution and fear, by the redrawing borders of Germany, Poland, the Soviet Union, the soviet-dominated and allies-occupied territories. Not a single member of my parents’ large extended families was alive. I do not understand how one moves on after such a tragedy. But move they did, and built a new life again, starting with having two children in quick succession, to focus on life rather than death. I was born in the German city of Breslau, which was renamed Wroclaw after it became a Polish city in 1945.

Our life in Poland was in many ways good. My parents became the new intelligentsia, my mother was like a sponge for catching up on all the formal education she had missed. Our life was cultured and interesting, my father was an executive in a large industrial state enterprise in Warsaw. But it was also bizarre. There was no family: no grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, like my friends. I was usually the only Jewish child in any school situation. We were secular people in a profoundly homogenous catholic country. I knew nothing of Jewish traditions and rituals, which my parents viewed as religious and therefore not quite for them; yet I was deeply Jewish (what else could I be in the xenophobic catholic Poland?).

And then came the year 1968. There was a political power struggle in the highest echelons of the ruling communist party, which required scapegoats. As it has been for centuries in that part of Europe, Jewish people became the convenient scapegoats. Within two months, totally out of the blue, we lost everything: my father’s position, our comfortable apartment, our dignity, our future. Staged demonstrations on the streets called for Jews to go where they belong: Palestine. The unrelenting official media called us the “fifth column”. After listening to a major speech by the First Secretary of the Party on TV, my mother turned off the TV and quietly said: this is the end, we must pack our bags. She was 54 years old and my father was two years older. They were going to be refugees again.

This time, I made the first move. More about that when I write about my life. This essay is about my parents. They came to America a year after I made it (my older brother came somewhat later). We landed in Saint Louis, not out of choice but accidentally (that is another long story). The suburban America, and especially the South, was a terrible landing pad for urban and urbane Europeans who did not speak English and did not drive, and who were used to seeing people and life on city streets. My father became a caretaker of the Hillel House at Washington University. It was a beautiful old mansion, and the job came with a small apartment. For my mother this decline in their social position was a deep shock. I think that she was ashamed. But not my father, who considered any honest job to be fine. In 1970 I moved to New York and within the next two years my parents and brother followed me. New York made sense to us, and we did not want to see Saint Louis again, ever.

And this is where this story becomes a true American immigrant story. At the Washington University Hillel, my amazingly resilient father reinvented himself as a specialist in building maintenance at Jewish Community Centers. He found such a position at the Forest Hills JCC in New York. This man, who has never seen air conditioning before coming to America, took charge of the HVAC system, the swimming pool, and all the other engineering systems. He was also in charge of the facilities for weddings, bar mitzvas and all high holidays. Since he had a gift for organizing working teams of people, he hired young Russian engineers immigrants who had just barely arrived in America, and who knew how to do these jobs. After all, he spoke fluent Russian. He helped them with settling in the new country and they helped him become a great success.

And he brought home tips: from happy fathers of the bride, from happy fathers of bar and bat mitzvah kids, and so on. Many generous tips. At this point of my story, my mother comes to the stage. She took that money and invested it. How did she figure out how to invest, this homemaker from impoverished shtetel family, and a communist? I do not know. But she invested well, especially during the high inflation years of the Carter Administration, and the high-yield bonds during the almost bankruptcy of New York City during the 1970s. Needless to say, my parents had a secure and long retirement years, spent winter in Miami Beach and summers in the Catskills. They travelled abroad.

My father died in their beloved New York City at age 100 and my mother at 102. Dementia took away from her the final several years, but until then, there was not a day, rain or shine, that my parents did not go either to Central Park, or City Corp, or a performance, always in the company of people with stories no less amazing than their own. One of their friends, who as a child survived the war hidden in a monastery, was working at the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. She ran down from the 50th floor and crawled under a parked truck just minutes before the building collapsed. A survivor is always a survivor. They never stopped walking the city streets (20-30 blocks was a typical “spacer”), they never stopped interacting with the great city. These were survivors. Whenever my spirit drops, I think of my indestructible parents, and I fearlessly face another day. And I also think of how lucky my children and grandchildren are to have multigenerational extended large families, which I have always missed so much.