This is an evolving story in many parts. I tell this story as it emerges, more or less chronologically, focusing on the parts in which I personally and the Energy Commission (the official name is Newton Citizens Commission on Energy) took active part.

It gets updated every few weeks or months.

Chapter 1. About Newton

Newton is a wealthy suburb of Boston, population 90,000, with high average income, very high educational attainment, and expensive properties. Its operating budget is over $500 million. Newton has very good amenities: superior public schools, fine city services, public transit to downtown Boston, cultural life, open space, a beautiful landscape, and proximity to both the countryside, Boston downtown, highways, and the airport. The majority of residents live in single or double family houses and 70% of them drive SUVs. The housing stock in Newton is beautiful but old, energy inefficient, and in a dire need of retrofits. About 90 percent of houses in Newton were built before 1970, and more than half were built before 1930.

Newton residents are predominantly white, politically liberal, and very active in local politics: they expect the politicians to listen and respond. We have a strong mayor, an unwieldy 24-member City Council, and a large and very active grassroots community. People in Newton are deeply concerned about climate change but are also averse to making changes in their largely comfortable lifestyles. There are many municipalities like Newton across the country and the world. We have a large consumption-based carbon footprint.

The size of the Sustainability Team in Newton is not easy to describe numerically: its two co-directors in principle share a single position but in reality represent about 1.5 person-hours; there is a full time Energy Coach; and there are two other professional employees who devote part of their time to sustainability matters (one in transportation and one in natural resources).

During the past four years the collective efforts of the activists and the Commission produced several results: Newton Climate Action Plan, GHG Emission Inventory, the City entered into electricity aggregation program with 80% renewables, large building developers are increasingly expected to meet the Passive House standard of construction, or close to it. But the most difficult tasks are still before us: private residences and commercial buildings need to drastically reduce their carbon footprint and to electrify their heating; and we need to drive less, let go of the huge SUVs and transition to EVs. Above all, residents and businesses need to take personal responsibility for their own GHG emissions.

Chapter 2. 2017-2019

Newton adopts the highest level of renewable electricity among the 360 Massachusetts municipalities.

Until about four years ago, Newton was virtually asleep with regard to climate action. The municipality did not consider the greenhouse emissions from non-city operations (97% of the total) to be their responsibility. And the greens in Newton have focused mostly on the traditional environmental agenda: waste recycling, tree planting, preservation of open space, water management, pesticide use, and so on. And on solar roofs.

The first major municipal action directed specifically toward GHG emissions from the residential and commercial sectors took place in 2017-18 around clean electricity. Notably, it was triggered by actions taken in the neighboring municipality, which, as I will highlight in this story, exemplifies horizontal diffusion of learning and policy innovation.

Massachusetts law allows cities and towns to adopt what is known as “community aggregation” or “municipal aggregation” programs for electricity. It was first introduced in Massachusetts in 1997 to increase market competition and is becoming increasingly popular among municipalities nationally. It works as follows: A municipality (or some other entity representing a town or another large community of households), serves as an intermediary in purchasing electrical power on behalf of all its residents. Such bulk procurement from sources other than a local utility which is regulated by the state, generally done through a consultant under a 1–3-year renewable contract, gives the municipality the leverage to negotiate better prices and to avoid large price fluctuations. Recently, power aggregation has been also used to increase the content of renewable electricity sources in the mix. An important feature of all aggregation programs is the opt-out option: people can choose not to participate by taking an active step of opting-out without penalties.

In recent years, aggregation has gained renewed popularity in Massachusetts (more than a hundred municipalities participate), with a novel feature: the municipalities channel the achieved savings toward increasing the renewable content in the electricity mix, the latter being usually more expensive. In short, the customers receive greener electricity without having to pay the price premium. A typical green content in Massachusetts has been only 5% above the state-mandated level provided by the local utilities (in 2018 it was 14%, with 2% annual increases).

In 2017 Newton started considering an aggregation contract. In the same year, a neighboring town – similar to Newton in a socioeconomic profile and in several respects our rival – adopted an aggregation program with 25% additional level of Class 1 locally-generated clean electricity above the Massachusetts baseline. This was a trigger for the grassroots organizations in Newton to call for a similar, and even more ambitious, contract for Newton. This quickly became a well-organized campaign, which took the Mayor totally by surprise; she thought of aggregation as an internal administrative matter, to be decided in her office.

The Energy Commission, which I chair since 2018, joined the campaign. The 9-member Commission collectively represents a very high level of expertise in science, engineering, energy systems analysis, management consulting, urban planning, building science, social science, and others. It was established in 1979 during the Carter Administration and partly in response to the OPEC energy crisis.

The Mayor was cautious, worrying about the political and human costs of increased electricity rates. The campaign responded by implementing a random survey to find out people’s willingness to pay. This was not a survey that would make it through a peer review process in a scholarly journal, but it was pretty good on scientific grounds: in designing the questionnaire, sample size and the target participants the members of the Energy Commission reached out to experts in the field. The interviewers accosted residents at key physical locations through the city. The Municipality tacitly approved doing the survey but left the sponsorship to the local activist organization Green Newton.

The result: an average household paying about $150/month for electricity was willing to pay an extra $10/month for about 56% of renewable electricity. These numbers became the centerpiece of the campaign.

The campaign was very successful. In 2019 Newton signed an aggregation contract with 40% Class 1 renewable electricity above the baseline (actually, these are Renewable Energy Certificates, or RECs, not “green electrons”). But we never had a chance to test people’s willingness to pay because, at that brief moment in time, the renewable electricity prices dipped.

Impacts:

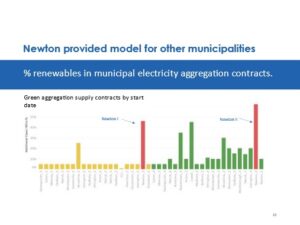

- The Mayor became so emboldened with her success that when the first 18-month contract expired, she signed a new contract in 2021 for 62% renewable electricity above the baseline, for a total of 80% renewable electricity (the graph below, with Newton I and Newton II marked). This time the cost to homeowners was about 7% higher than if the electricity was supplied by the local utilities. Nobody complained.

- About 10% of residents opted out of the program. Otherwise, nobody complained. People barely noticed the higher price.

- The grassroots activists and Energy Commission learned that they can successfully campaign.

- Within a year, other communities in MA adopted aggregation with higher than 5% renewables. The graph below shows the timeline of municipalities adopting aggregation and the level of renewables. The action by Newton had a big effect on other municipalities. This horizontal diffusion of learning is an important avenue for social change on a municipal level.

- For the first time, Newton has made a major decision addressing greenhouse gas emissions from the residential sector.

- Newton acquired a reputation of being a sustainability leader in Massachusetts, which hopefully gave the Mayor some political capital for making more difficult decisions in the future. It also raised expectations.

As of 2025, Newton Power Choice is in its third contract. The content of clean electricity is 95%.

Chapter 3. 2018-2019

Newton adopts a Climate Action Plan

In 2018, the newly-elected mayor won by a very narrow margin, largely thanks to strong support from the environmentally engaged community. Her campaign promise was to develop during her first year in office a climate action plan. In 2019 she engaged a consultant for the City to do just that. Environmental activists and the Energy Commission were invited to the table where the scope of the project was to be discussed. It became very clear very soon that for various reasons the plan the city was going to get would be an off-the shelf template document of little use in setting implementation priorities and goals, or guiding the implementation process.

This gave the Energy Commission an impetus to get to the finish line ahead of the City with its own climate action plan. Over a period of about eight months, the group spent many hundreds of volunteering person-hours on that project, with no budget. The resulting 130-page document, the Citizens Climate Action Plan, was handed to the Mayor shortly before the consultant completed their work. It contained an extensive quantitative analysis and modeling of Newton’s circumstances – the building stock, the private car fleet, the turnover of houses and cars, the demographics, and so on – followed by specific recommendations for priority actions and the approaches for achieving the overarching goal of carbon neutrality in 2050. I then proceeded to meet each member of the City Council (all 24 of them) over coffee to hand them a copy of the document and explain its significance.

The Plan does not address consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions, focusing instead on more traditional emission accounting from direct use of energy: heating, cooling, cooking, mobility, and electricity use. Newton was not ready for it, and in any case, we do not have the technical capacity to develop one. But its driving rationale is “personal responsibility for significant reduction, not just gestures like recycling of reusable shopping bags”. I hope that by confronting Newton residents with this personal lifestyle challenge, we are making a significant step toward re-examining the impacts of their consumption and lifestyles on climate.

The Citizens Climate Action Plan was formally presented to the City Council in August of 2019. It garnered unanimous support from the City Council and forced the hand of the City to produce a high quality “official” plan several months later. The environmental community in Newton also raised its voices, calling for carbon neutrality by 2050. The official Newton Climate Action plan was largely modeled on the Citizens Plan. Its most important feature was that it identified priority actions and adopted very specific numerical goals for 2050 and interim progress milestones. In other words, it created a mechanism for accountability.

In December of 2019 the official Newton Climate Action Plan was unanimously adopted by City Council. And about a year later (after some COVID-related delays) the City created a new position of Energy Coach and filled the position with a young, energetic, smart and highly motivated person.

This incident gave the Energy Commission a high standing in the community as a highly competent body whose advice should not be ignored.

Two political lessons for the Energy Commission and the activist community: 1. City Council can be a powerful ally in mobilizing the Mayor toward our objectives; 2. In a municipality, all politics is personal.

Chapter 4. Energy Coach Service

In the post-Climate Action Plan atmosphere, the Energy Commission created an Energy Coach Service through which residents could get advice on energy-related questions from volunteer residents with expertise. The city eventually took over this function and in 2021 hired an additional staff member (Energy Coach) in the Sustainability Office to run it. The position has since changed its name to Energy Coordinator.

Among the numerous job responsibilities of the Energy Coach, the largest is to implement a campaign directed at homeowners. With help from volunteer professionals in communications and web design, a campaign with a slogan 4Our Future was developed, focusing on four areas of voluntary actions: solar roofs, insulation, electrification of heating, and electric vehicles. The idea was to assemble a large number of volunteers who would then engage in peer-to-peer communications and over time build a large network for communication and encouragement. Green Newton, a prominent local organization, is working closely with the city on this project.

Chapter 5. The grassroots community takes action for climate protection

The long process of creating the Climate Action Plan, CAP, injects energy into the climate activism in Newton. Here, I mention those that stand out in my mind as visible, well-organized, dynamic and effective.

-

- Building Standards Committee

Green Newton, the highly regarded and very visible local organization, established the Building Standards Committee, BSC. It comprises architects, progressive small local developers, urban planners and other professionals, and one city councilor who is also an architect. The initial work of the BSC, going back to about 2018, was to introduce a new criterion in the review by the City Council of applications for special permits to build large buildings: consideration of environmental impacts.

After this modest success the BSC took on a bigger task. They started identifying developers of multi-unit residential buildings who were seeking special permits from the municipality (City Council’s job), and then approached them with proposals to adopt fully electric heating with air pumps and a highly insulated construction method known as Passive House. Their modus operandi was a combination of pressure, persuasion, and highly sophisticated technical advice. In 2020, the BSC scored a major victory when a large national developer, Northland, headquartered in Newton and adopted these principles of construction for a large project consisting of about 800 apartment units. The project became very controversial because of its size, greatly polarizing Newton between the pro- and anti-development supporters (See Chapter 7 below). It culminated in a city-wide referendum in March 2020, in which the project won in a landslide. I became deeply involved in the campaign supporting the Northland project, and after they received the permit I published an article about it in Commonwealth Magazine “How Newton Bridged the Housing Divide”.

After the Northland victory, the prestige of BSC grew and its agenda as well as its effectiveness rapidly increased. This small group of volunteers put an outsized imprint on the types of residential building projects taking place in Newton. Looking at their work through the theoretical lens of socio-technical transitions, the change they introduced to Newton took place on the accelerated section of the S-curve of transitions; each new development project was a little easier to fight for and to justify. By the end of 2021, the BSC was responsible for about two dozen building projects executed to very advanced sustainability construction standards. And the City Council became educated in the process about Passive House.

-

- Electric Vehicle Taskforce was established sometime in 2020 to advocate for a rapid adoption of EVs in Newton. I do not elaborate here on their many activities.

- A Future Without Gas coalition, AFWOG

AFWOG is a very active grassroots coalition seeking to eliminate the use of natural gas. Its origins precede Newton Climate Action Plan. They are grounded in the campaign against leaks from old pipes as a health risk and as greenhouse gas emissions, but over time its scope has widened to include challenging the actions of the gas utility National Grid to maintain their gas pipe infrastructure indefinitely. AFWOG has had many small successes both in Newton and on the state level, through its own research and through links with larger organizations with similar goals.

Chapter 6. Implementation is anemic

But the hardest job is still ahead: mobilizing residents and businesses to upgrade existing buildings toward higher insulation and replacing gas with heat pump heating systems. Existing buildings are the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Newton.

The Newton Energy Coach was hired in early 2021. As mentioned above, among the numerous job responsibilities of the Energy Coach, the largest was to develop a campaign directed at homeowners. With the help from volunteer professionals in communications and web design, a campaign with a slogan 4Our Future was developed, focusing on four areas of voluntary actions: solar roofs, insulation, electrification of heating, and electric vehicles. The idea was to assemble a large number of volunteers who would then engage in peer-to-peer communications and over time build a large network for communication and encouragement. Green Newton, a prominent local organization, has worked closely with the city on this project.

But the Energy Commission was skeptical from the outset. It has been shown time and time again that information, persuasion, and campaigns do not yield significant results. This is because it requires several factors to work in tandem: people paying attention and internalizing the message, knowing what to do, finding trustworthy professionals to do it, financing the work. It is highly unlikely for these factors to be present all at the same time. I do not know if the City Sustainability team has internalized these barriers, though they certainly have heard it from me numerous times. My guess is that if pressed, they would admit that reality but prefer not to think about it because it implies taking more coercive and politically risky actions.

Early in 2020 the city created the Implementation Working Group for Climate Action Plan, comprising representatives of the Energy Commission, EV Taskforce, Green Newton, the entire municipal team working on climate and sustainability (5 individuals with various levels of assignments toward that topic), one city councilor, and the Mayor’s community outreach director. A highly regarded grassroots activist chaired the Implementation Group. This group had the potential to become an important venue for open conversation about CAP implementation by the City and about accountability.

But over time the Implementation Working Group fizzled out without delivering on its potential. Its functions shrunk to become a forum for exchanging information and updates on actions taking place elsewhere in the City, namely:

-

- Energy Commission, which about in 2021 introduced the idea of BERDO ordinance in Newton (see below);

- EV Task force, which advocates for charging stations, electric school buses and others, and organizes various events to inform Newton residents about electric vehicles;

- Building Standards Committee within Newton, which very successfully works with developers to adopt Passive House building methods for large residential new construction;

- 350Mass-Newton node, which advocates for state legislation focused on Climate protection;

- Mothers Out Front-Newton node which focuses primarily on gas leaks and on transitioning away from using natural gas.

Chapter 7. Civil war over high density housing development. 2016-2020

Between 2016 and 2020, Newton experienced a bloody conflict between opponents and proponents of a proposed construction of a large residential housing project. It is the type of conflict that plays out in hundreds, if not thousands, of communities nationwide: between citizens who want to preserve the village-like character of their suburbs by keeping exclusionary zoning intact (slogan Right Size Newton); and proponents who want to contribute to the growing housing crisis in their communities and beyond by welcoming more residents and building larger and more dense housing (slogan Newton for Everyone).

For several reasons local environmental advocates largely supported the proposed project. First, high density is associated with lower per capita energy use; Second, under the influence of the Building Standards Committee in Newton, Northland Corporation (the developer) committed to make the buildings Passive House (PH) certified, which would make it the largest PH project in Massachusetts. Third, most environmentalists share a progressive value system concerned with the collective good, such as more affordable housing.

The fight took several years, numerous revisions and public hearings, and in the end landed in the ballot box in a city-wide referendum. The result was a landslide victory for proponents of the project but the long-term effect was swift and unambiguous. During the next two biannual election cycles, several progressive city councilors were replaced by more conservative council members who generally oppose higher density multistore residential buildings and want to preserve exclusionary single-family zoning.

I told that story in an article published in CommonWealth Beacon magazine in 2020.

Chapter 8. 2020-2021. Citizens Commission on Energy takes initial steps toward implementing the most challenging provisions of Climate Action Plan: improving energy performance of current buildings.

The focus of the Energy Commission is on residential and commercial buildings. We take two initial steps regarding the residential sector: public posting of energy efficiency rankings of homes; and creating energy coaching services for homeowners.

Posting HERS ratings. As the first step toward getting the homeowners engaged with their energy use, we worked with the city to post energy efficiency ratings of homes on a publicly accessible database: The Tax Assessor’s database. Through a state law, since 2010, all newly constructed homes in Newton must meet a certain minimum energy efficiency rating score, the so-called HERS rating. Since 2017, this is a state-wide requirement in Massachusetts.

The assessor’s database is the most frequently used page on the City’s website. It posts detailed information about each house, including the history of its sale prices, the type of heating system, and the size. The HERS ratings have now been added to the list of these features. Unfortunately, it only affects houses built and radically renovated since 2010, which represents only a small fraction of the total.

Energy Coaching. In 2020, we developed the Energy Coach website in order to provide advice to homeowners on a variety of energy-climate-retrofits topics. The website has hundreds of questions and answers, and it has a portal for making appointments with any of the several volunteer experts. The City loves this service. In the summer of 2021, the City took over the management of the site and the coordination of the meetings with residents. The newly hired Newton Energy Coach manages this process. The Energy Coach service receives high marks from all who use it. But not a lot of people do so.

Coaching responds to homeowners who are already involved in energy upgrades of their homes. They are a minority. Furthermore, the commercial buildings are a challenge that has not been tackled at all. It is going to be very hard to mobilize the City to do anything about these two biggest emitters of greenhouse gas emissions in Newton, because any kind of coercive policy proposal will be politically very risky.

Chapter 8a. Covid Pandemic Slows Everything Down between 2021 and 2022.

Chapter 9. We are still not making measurable progress: Newton Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory

Since the adoption of the Climate Action Plan in December of 2019, the foundation has been set in Newton for taking meaningful steps toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions: the Energy Coach hired, Energy Coaching Service installed, HERS ratings of new homes publicly posted, BSC works toward future reductions from new construction, the EV Taskforce is working, the City is developing an outreach campaign for homeowners. But we on the Energy Commission suspect that none of these are currently leading to actual measurable reductions in energy use in Newton. Furthermore, the City does not have a strategy on how to reduce energy use and is not interested in developing one. And because the impressive Power Choice contract for 80% renewable electricity gave Newton the reputation of being a leader, nobody is in a hurry to do anything drastic.

I raise these critical issues in my presentation at Newton Public Library in March of 2021. The virtual presentation is well attended, including several city councilors and the City Sustainability Team, but it does not have any visible impact.

We need facts and figures to draw the attention of the government and activists to that reality, and to open the door for bolder and more coercive policy initiatives. In the summer of 2021, the Energy Commission develops a Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory, the first such update since 2013.

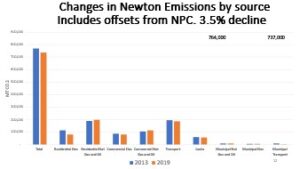

The Inventory went public in November 2021, and it indeed showed no progress in energy demand, with the only reductions in GHG emissions being attributed to the green electricity contract.

Among its conclusions and recommendations are these:

“Continuing the current trends in energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions virtually guarantees that Newton will not meet its stated goals. While we made progress in shifting toward a more renewable electricity mix through NPC, the accounting reductions so produced are being counteracted by a growing demand for heating fuel in the residential, commercial and municipal sectors.”

“No matter how large, the resources never match the challenges. We should therefore focus our energy on actions that are likely to succeed rather than actions that we know how to implement. Our strategies and tactics should be evidence-based. The fields of sociology, behavioral economics, management and others offer a large body of research and knowledge on how to effectively change individual, institutional and business behaviors; what works and what does not work. There lies Newton’s best hope for the innovations needed in its next steps.”

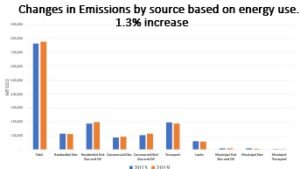

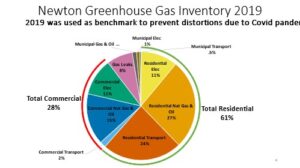

The graph above shows that commercial and residential buildings are the primary source of GHG emissions in Newton (this is a traditional inventory, not consumption-based). And since relatively few new single- and two-family houses are built annually, we estimate that it will take several hundred years for the current housing inventory to be replaced with new and highly efficient construction. Something needs to be done about existing buildings.

Chapter 10. Addressing commercial building emissions: BERDO

A great opportunity arises in 2021. In September of that year Boston, the main city in Massachusetts and only a few miles away from Newton, adopts a very innovative policy regarding large commercial buildings of 20,000 square feet or larger. Under the name BERDO 2.0, it mandates two things: annual reporting of energy use and GHG emissions per square foot; and meeting specific GHG emission standards. The former requirement (under the name BERDO) has been on the books for many years, but despite a high compliance rate it produced no significant reductions in GHG emissions. This is why Boston moves to adopt the latter requirement; a mandate to meet specified performance standards, tailored for 13 different types of buildings. These performance standards get tighter every few years until reaching net zero in 2050. The program has significant financial penalties for non-compliance. At the time of writing, specific regulations are being developed for BERDO 2.0.

Boston’s BERDO 2.0 is a path breaker. While there are more than a dozen programs around the country (including Cambridge, Massachusetts) which require regular reporting of energy use intensity, none set enforceable specific emission standards for buildings. This is a template policy we on the Energy Commission have been looking for. Within weeks of the Boston ordinance, the Energy Commission informally introduces a proposal for a BERDO 2.0-like program in Newton: in informal conversations with sympathetic city councilors and through the CAP Implementation Working Group. The idea is quickly embraced by several city councilors. After the initial reservations, over the next three months the Sustainability Team of the City also warms up to this policy proposal, clearly with at least tacit approval from the Mayor to cautiously proceed.

Chapter 11. Unfolding of the BERDO strategy

This part of the story is evolving. The general strategy for Newton BERDO is:

- To engage the owners of large buildings and hopefully gain support form most of them.

- To build on the work of the Boston team with regard to technical specifications and regulatory requirements; e.g. to maximize the horizontal diffusion of learning.

- To secure the Mayor’s support in order to identify the necessary resources to implement Newton BERDO.

- To persuade the City Council to adopt the BERDO ordinance sometime before the end of 2022.

Chapter 12. BERDO ordinance develops

In the late spring of 2022, with tacit approval from the Mayor, the City makes an official commitment to work on developing BERDO ordinance. They create a website, form a team of staff members, and invite two people from the Energy Commission (me and my colleague) to participate in the weekly meetings. After the first couple of meetings a question arises that requires expertise from another Commission member. He is invited to one meeting, then another, and he stays. This way, our BERDO team is balanced; three people from the municipality and three people from the Commission. Over time, a representative of Green Newton joins the working group and one of the city staff gets assigned to other responsibilities. We are still 6 but somewhat differently balanced.

We work as a single team, largely because the Energy Commission provides crucial expertise and a willingness to work for free. The city would not be able to do it on their own. There are several key decisions to be made, all requiring analysis, discussion, consideration. Some examples: what should the minimum size of buildings covered by the ordinance be; should Newton adopt the same emissions standards as Boston; should large residential properties be included; what time table to use for implementation; how to reach out to the building owners to explain and avoid political surprises; how to allocate the funds that will be collected from fees and fines; how to involve the utilities in helping building owners with data assembly for annual reports on energy use; should smaller buildings have more time for compliance than large and professionally managed buildings; how to count Renewable Portfolio Standards (RECs) in calculating GHG emissions.

Between March and June/July these decisions all get made by our team of six. On some of those, such as an implementation timetable for different types of buildings, and the inclusion of large residential properties, the Energy Commission takes the first step, and our proposals get accepted partly because there are no strong counterarguments. The passing of the ordinance gets tentatively scheduled for February 2023 (in reality, it would take until December of 2024).

Starting in June, the Sustainability co-director and the key member of the Energy Commission begin a series of outreach presentations and Q&A sessions for the commercial real estate community. By the end of August of 2021, five information sessions have been offered, each attended by about two dozen people, and moderated by another volunteer: the Chairman of the Board of Green Newton. Over time, the presentations get more concrete, as the decisions about the details of the ordinance get made.

State and local legislation improved the climate for our work. Between 2022 and 2023 Massachusetts adopted three laws with consequences for energy use and GHG emissions from buildings in Newton. These are:

- A new opt-in Building Stretch Code, with much higher energy performance standards than the previous version and strong incentives for electrification. Newton is among these so-called Stretch Code communities that adopted it as well as its even more ambitious version, Specialized Stretch Code.

- Governor signs a new Climate Legislation for the Commonwealth, which, among several excellent provisions, creates a requirement that all buildings above 20,000 square feet must annually report their energy use. Compared with Boston, and hopefully Newton, BERDO this is a small step toward accountability of building owners for their energy use, it is becoming clear to all building owners that the trend toward disclosure of energy performance is here to stay: sooner or later they will have to do it even if Newton’s BERDO were to be defeated.

- The Mass Climate Bill also provides for ten municipalities to experiment with a prohibition on installing gas heating in new construction. Newton City Council approves Newton’s application to become one of the Ten Communities. Newton is selected by the state legislation as one of the Ten Communities Pilot program which requires all new construction to be heated by electricity.

- In compliance with the state law, Newton adopted a revised zoning ordinance, which requires that communities served by the state public transit system (MBTA communities) designate certain areas for higher density development.

These new policies will over time produce housing in Newton that uses less fossil fuels per capita or eliminate them altogether. They are an investment in the long-term future. But they have little effect on the existing buildings. Furthermore, most of the existing residential houses will still be here by 2050 because the replacement rate of the existing housing is about 0.5% annually. And since there is very little open land left for additional construction in Newton, improving the performance of new development will have a relatively small overall impact on the city’s greenhouse gas emissions.

In the spring of 2022 Newton City council also adopts what is called PACE legislation, which is an interesting program for long-term financing of energy upgrades of commercial buildings. That may prove very helpful to some building owners that would be covered by BERDO.

Chapter 13. What about energy use in the residential sector?

By the end of 2022, it becomes clear that developing and adopting BERDO ordinance will be a long process. In the meantime, the existing residential sector, responsible for 38% of greenhouse gas emissions in Newton, receives little attention from the Administration and City Council. At the current rate of replacement, by 2050, 80% of Newton’s current housing stock will still be in place. These structures are largely energy inefficient. The Climate Action Plan calls for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20% through insulation and by another 80% by replacing gas heating with electric heat pumps. Massachusetts has a robust program, Mass Save, that provides homeowners with free home energy assessments and generous subsidies for insulation and other energy efficiency improvements. The program is not perfect, but it has great potential to improve energy efficiency of homes. Unfortunately, a relatively small number of homeowners use it. The Newton Climate Action Plan calls for approximately tripling the number of home energy assessments and insulation projects in the next couple of years, but there is little evidence that this will happen.

Partly, the problem is the voluntary nature of the program. As shown by scientific research and decades of national experience, voluntary programs compete with other urgent demands for attention in people’s lives and rarely rise to the level of visibility required for taking action. Other barriers include: unfamiliarity with technical matters, lack of knowledge about what actions are needed, feeling powerless because of the highly technical challenges involved, confusing and inconsistent advice, lack of trust in contractors, and general reluctance to tackle potentially large, expensive and time-consuming projects.

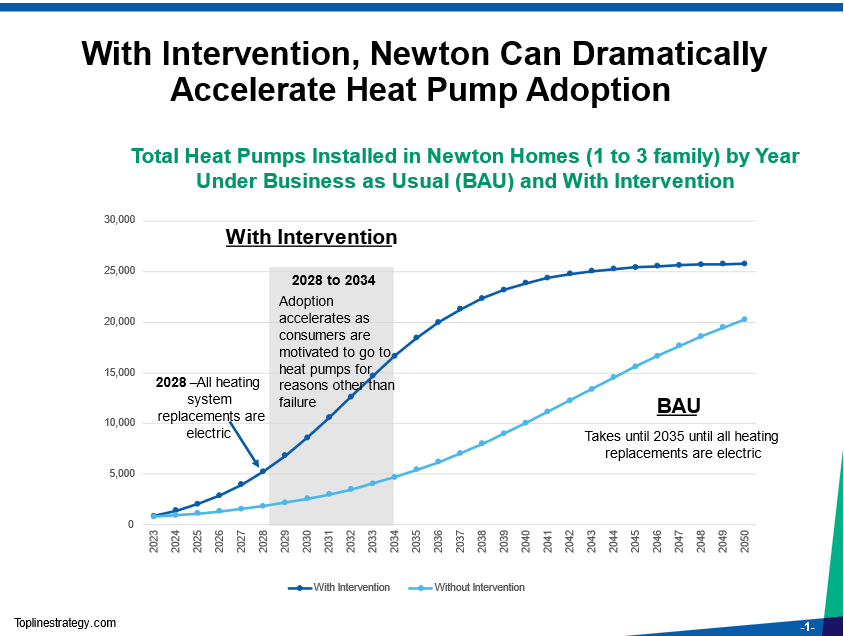

The NCCE’s analyses performed in 2019 for the Citizens Climate Action Plan estimated that approximately 800 completed weatherization projects and 450 heat pump installations would need to take place each year for the next 30 years for the rate of progress to achieve the Year 2050 target of Net 0% residential emissions. The three years of implementing the Plan have, so far, resulted in the running rates of annual energy efficiency projects and heat pump installations at about 42% and 12% of the needed rates of progress, respectively. Even allowing that start-ups can be slow and that we anticipate subsequent acceleration for the program implemented so far, Newton will continue falling further and further behind its stated goals, without significant acceleration.

NCCE therefore embarks in 2023 on developing a strategic plan for addressing this issue. Its starting point is a simulated comparison of the rate of home retrofits at the current rate with that necessary for meeting Newton Climate Action Plan.

The figure below shows the results of the most recent NCCE analysis of the rate at which Newton homes will be retrofitted. At the current rate of progress (No Intervention scenario), by 2040 about 40% of the homes in Newton will be retrofitted. In the Intervention Scenario, based on the implementation of the five recommendations in this document, we estimate that by 2040 all residential homes could be retrofitted. For comparison (though using a different metric, namely greenhouse gas emissions), the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan calls for 50% reduction by 2030 and 75% emission reduction by 2040, relative to 1990. The Commonwealth’s statewide efforts toward “gas-free future” will fall short of their goal if people do not put in place the physical construction needed to weatherize and electrify their homes. Significantly faster progress is the strategic objective. Implementing a well-designed and strategic operational plan and implementation roadmap will accomplish it.

The resulting document, Recommendations For Meeting Goals For The Residential Sector was presented to the Mayor on April 12, 2023. The document presents five strategic near-term recommendations in the form of Recommended Action Items, with an underlying problem statement and justification. The Commission has asked Mayor Fuller to translate these Recommended Action Items into the City’s operating plan, with the policies, ordinances, attributions of specific tasks, procedures, timetables, budget, staffing, semi-annual progress reviews, and the managerial oversight necessary for timely success.

After several follow-up meetings with the mayor and the staff of the Sustainability Office, NCCE found itself at a dead end. No meaningful action was taken by the mayor, and no plan was developed. The document joined many other planning documents on a shelf. But the effort was not totally wasted. Over the next few years, Residential Recommendations served to educate the grassroots community members and Newton City Council. From then on, the issue of the residential sector became part of the conversation about climate action in Newton, enhanced by the ongoing efforts on BERDO.

Chapter 14. BERDO finale: from the fall 2023 to December 2024

In November of 2023 the draft of the BERDO ordinance was presented to the Zoning and Planning Committee (ZAP) of the City Council. This marked the beginning of the active political process.

One issue remained unresolved, namely the multifamily buildings. Among the members of the BERDO Working Group, one Sustainability Co-director and the representative of Green Newton were against including them. For one of them, the resistance was political: a concern that the opposition from the residents may derail the entire ordinance. For the other, the fairness argument was key: why regulate owners of condos while owners of large single-family homes are left alone. The remaining members of the Working Group argued that multifamily buildings are no different than any other large buildings and should not be excluded; and that BERDO was only the first phase of addressing greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, and that the residential sector would be next. Over time, one of the two opponents changed his position, and a sort of tacit agreement emerged within the group that we would follow the majority recommendation (5 to1) to include multifamily buildings.

This is not what happened. Sometime in early 2024, shortly before presenting the final draft ordinance to Zoning and Planning Committee of the City council (ZAP) and scheduling public hearings, the mayor removed the multifamily buildings from the text of the ordinance. It was a surprise to everyone. As a compromise, the mayor proposed including multifamily buildings (on the same implementation schedule) a year later through an amendment. For several reasons, that was very unlikely: 2025 would be an election year for the mayor, hardly a time for controversial policy proposals; the one year delay would gain little for building owners and would only accomplish a delay in their planning for energy improvements and give them less time to prepare for the compliance deadline; the legislators would be tired of this topic, reluctant to return to it.

In September 2024 the Sustainability Office, through its consultant Synapse, presented to ZAP the full draft ordinance and its supporting materials. The ordinance did not include multifamily buildings.

Nonetheless, the mayor committed approximately $200,000 annually to create a full-time position of BERDO coordinator. This puts ZAP’s mind to rest about the forthcoming administrative demands should BERDO be adopted.

At this point, the NCCE resorted to a two-pronged political campaign to put multifamily buildings back into the ordinance: mobilize the local grassroots organizations (Green Newton, 350.org-Newton Node, Mothers Out front-Newton Node) and the League of Women Voters of Newton; and reach out to the individual members of ZAP. Many scones and cups of coffee were consumed in Newton cafes by me and almost every member of ZAP: explaining, trying to understand the mood and thinking of these individuals, and so on.

One strong supporter of BERDO introduced an amendment to put the multifamily buildings back into the ordinance. The subsequent debate, and additional public consultation that ensued, had the benefit of engaging and educating the full 24-member of Newton City Council. That education was essential in passing BERDO because it is a complicated ordinance and its essence – regulating air pollution – is a very new territory for a municipal government. If the City council members would not understand its detailed workings, they would most likely take a prudent position of rejecting it. Another challenging feature of this ordinance is that it asks local building owners, businesses and residents to pay for something that benefits the world at large rather than only to locality.

The big questions on everybody’s mind were these: how much will the compliance with BERDO cost, and how will it affect rents. These were very difficult questions to answer because Boston BERDO 2.0 has not been effective long enough to generate data on the cost of upgrades and their downstream effects. Based on the four case studies in Newton and data available from other programs, the best estimate is that it may raise rents by 2-4%.

The vote in the ZAP committee took place sometime in November of 2024. ZAP unanimously adopted BERDO and the proposed amendment to include multifamily buildings. But since this was a change in the draft BERDO ordinance formally presented to the public several months earlier, it required reopening of the public process.

The final public consultation, this time over the ordinance including the new amendment, attracted a very large attendance by the residents of two towers (Towers at Chestnut Hill, with more than 400 residential units). They loudly protested inclusion of multifamily buildings in the ordinance. They had two key arguments: 1. The rest will go up and nobody can tell us exactly my how much; 2. Why are we singling out the people living in compact spaces and allow the more than 20 thousand single and two-family houses – many of them very large — to do nothing?

It was hard to dismiss these arguments with such logical statements as: “the multifamily houses are the first step, we shall address small houses next”; or “everybody must bear some cost for protection the climate, and this one is not expected to be large”.

In its wisdom, in preparation for the final vote in the City Council, the Administration created three versions of the ordinance, to be presented to the full city council: without multifamily buildings, with multifamily buildings, a hybrid version whereby multifamily buildings would be required to report annually their energy use and greenhouse gas emissions intensity but would not have an obligation to meet performance targets.

The final vote on the ordinance took place on December 16, 2025, 3.5 years since NCCE first proposed this idea to the city.

The hybrid version was adopted unanimously. The unanimous vote for anything is a very rare occurrence in the history of our 24-member rather polarized city council. It spoke to the realization by its members that the time has come for our city to take a significant step toward climate protection and that everybody wanted to earn their bragging rights for supporting such a policy. It was a truly rare moment of unity after the past several years of a bitter debate over zoning (see my recent writing about Newton BERDO).

I would have liked to see multifamily buildings fully covered by the ordinance. But even under the compromised version, the fact that multifamily buildings have to track their energy use and greenhouse gas emission intensity, and have them publicly posted, is a major step forward. It will engage Newton residents with energy use and greenhouse gas emissions associated with their lifestyle choices. It also opened the door for future actions with regard to the residential sector. These two points were the essence of my personal hidden agenda in the work on BERDO.

Chapter 15. Postscript to the BERDO story.

Three-and-half years is a long time to develop and push through a single ordinance. It could have taken maybe a year less if the Sustainability Office had made it a top priority on its agenda. But the fact is that policy process is and always will be slow. In retrospect, considering that the Mayor and her main sustainable co-director and most trusted advisor were not especially enthusiastic about this ordinance, we have done extremely well to get it adopted, and unanimously to boot. The elements of that success include these:

- From the start, NCCE assumed the role of an equal partner with the municipality by having three of its members become part of the 6-person team working on BERDO. The other three members were: two co-directors of the Sustainability Office and a leading member of the Green Newton Board and a leader of Newton Building Standards Committee. One of the sustainability co-directors was deeply invested in making BERDO a success and he provided excellent leadership for this effort.

- By the time NCCE undertook the BERDO work, we had a strong standing in Newton with regard to the executive and legislative branches. The work we conducted since 2018 on Climate Action Plan, the Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory, the Newton Power Choice, and various other issues, have established us as competent, persistent, and honest broker of consequence in Newton. Our work could be trusted.

- During the first 2.5 years of the BERDO process, most of the technical analysis was done by the NCCE members. In the final year, a very competent consultant provided additional technical support.

- Learning from the experiences in other jurisdictions, especially in Boston BERDO 2.0, Cambridge BEUDO and Maryland State, Newton BERDO made several changes in comparison with the Boston policy, Newton’s starting model. These included: slower pace of reductions in the performance targets; stretched out time table for the start of compliance (with the longest period afforded to small residential buildings); eliminated electricity from the calculations of greenhouse gas emissions (to avoid the complications arising from a wide range of electricity providers, each with their own content of renewable generation, and because of the expectation that the Massachusetts grid would be close to 100% clean within a few years).

- A series of outreach and educational sessions for building owners and the leadership of the Chamber of Commerce. And close communication with the Newton Housing Authority which provides affordable and senior housing.

Most of all, the BERDO story supports my idea that the most effective advocate for a particular policy is one that can combine technical expertise with an ability to relate to and communicate with people. For me, it is not a new discovery. When I worked at the state agency, I was always puzzled by the principle of separating the people who do the risk assessment from those who do risk management and often from those who speak to the public. I understand of course that the first separation is intended to keep science unbiased. But there is a difference between the process of scientific analysis and policy making, which do need to be viewed as separate, and the people who do these things.

Of course, not everybody can do it. I seem to have this gift. Most of my colleagues experts would not be as comfortable as I am with personal politicking. And many people who are attracted to politics do not have technical expertise. I love doing both. Which is why, when I worked for the state agency, my boss always put me in front of very angry communities whose water or air or soil was contaminated with toxic chemicals.

Notably, when the final presentation about BERDO was made to ZAP, it was the consultant who gave it. Several of us working on BERDO for over three years could have given such a presentation. But having the consultant do it gave the process the feel of neutrality and thus more trustworthiness in the eyes of the skeptic. It was a great idea.

After the Newton BERDO ordinance was unanimously adopted on December 16, 2024, I gave a presentation to Building Electrification Accelerator, BEA, a small but very active non-profit organization in Massachusetts, focused on retrofitting residential properties. The presentation emphasized the policy process and people involved in it.

Chapter 16. Something must be done about the existing residential sector

The existing residential sector comprising mostly single- and two-family houses is responsible for 38% of the city’s GHG emissions. This is typical for residential communities in New England, where houses are old. So far, the outreach by the city and the grassroots organization Green Newton to mobilized homeowners to insulate their homes and to install heat pumps have produced very modest results. The Energy Commission discussed the reasons for this slow progress in its 2023 Recommendations For Meeting Goals For The Residential Sector. The strategic plan for addressing this Achilles heel of climate action fell flat when first presented to the mayor. But the issue has not gone away. In fact, the BERDO ordinance has put it again on the mental radar of several city councilors.

While all agree that BERDO-like regulatory policy would be politically and administratively impossible to put in place, so far consensus among the Commission’s members has not yet emerged regarding how to proceed. Some members propose to modify and strengthen the voluntary outreach to homeowners as the only workable approach. Others want to adopt a reporting requirement (Energy Use Intensity score, EUI), which the city would post on the Assessor’s database, along with many other features of each property (ownership, purchase price, water use, property tax, number of rooms and bathrooms, fuel type, and others). They argue that such a policy would have several benefits:

- Inducing homeowners to engage with the energy performance of their homes;

- Identifying homes most in need of greater energy efficiency, relevant professional advice, and help from the Newton Energy Coach service;

- Providing a mechanism for homeowners to compare their homes to others, using a simple metric, and for energy-efficiency competition among homeowners with different ratings through public posting;

- Stimulating the demand for retrofits and adding to local economic activity;

- If deemed necessary, provide the basis for developing additional data-driven future policy instruments that would mobilize building owners to improve their properties.

- It would impose both responsibility and accountability on building owners. It would drive home the message that what people do with their homes impacts local and global communities.

One of the members of the Energy Commission has developed an app for calculating EUI from the data on the use of natural gas, heating oil, propane and electricity, and the square footage of a house. The app is extremely easy to use.

This story will continue…