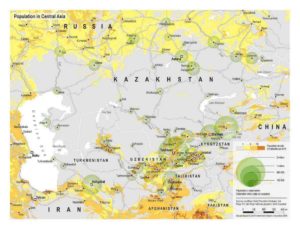

Uzbekistan and its neighboring “-stans” is that spot on the map — between eastern-most Europe, Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and Afghanistan – that, although once a big player in the history of Europe and Asia, for most of us is a blank space. So we take this trip in order to put some color and pattern into that space. We also have personal reasons to go there. For Philip, this is a return trip, after 23 years. For Halina, Uzbekistan is the place where her Jewish parents spent about 2-3 years during WWII, escaping the Holocaust.

Uzbekistan and its neighboring “-stans” is that spot on the map — between eastern-most Europe, Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and Afghanistan – that, although once a big player in the history of Europe and Asia, for most of us is a blank space. So we take this trip in order to put some color and pattern into that space. We also have personal reasons to go there. For Philip, this is a return trip, after 23 years. For Halina, Uzbekistan is the place where her Jewish parents spent about 2-3 years during WWII, escaping the Holocaust.

Towards Tashkent, Monday, Oct 1

Schiphol airport is like a factory, efficiently churning out thousands of travelers. Frankfurt is a nightmare. No signs, wrong information, different terminal. We thought we were late for the connecting flight, but in the end we caught it easily, thanks to Philip who brazenly checked in at the business class line. The Tashkent airport is new and handsome. All the information we had about many forms to fill out, money to declare, the bureaucracy, etc., does not apply anymore. Progress.

We get picked up at the airport and within 20 minutes arrive at our hotel Gloria. Our neighborhood is dominated by a wide boulevard with four lanes of car traffic each way, like a highway. But the hotel is located in a small alley, quiet, with birds singing and a small outdoor patio with tables and umbrellas. After settling in we explore the immediate neighborhood searching for some food while having no local money. Halina has her first Russian conversations, which helps. We end up in the neighboring Grand Mir hotel where a credit card buys us lentil soup and bread.

Tashkent, Tuesday, October 2.

Perfect summer weather: dry and in the 80s. No discernable pollution or diesel smells. We have one day to take in this city.

Tashkent is a sprawling modern metropolis crisscrossed by grand boulevards similar to ours and wide sidewalks. The residential buildings are mostly 5-7 story high, some modern some from the Soviet era. We head for the metro. Like the Moscow metro, this one is built to proclaim a communist glory: elegant, grand, quiet, fast and efficient. These people would laugh at the T in Boston. The turnstiles do not work at our station so there is a young woman checking if we insert the tokens before entering. Next to her an armed security man. As the day goes by we see many security guards stationed in key locations, and always in the metro. As a visitor I like it of course.

We get off at Komsomolskaya station for a few minutes to admire the wall paintings of the heroes of the space travel: from Icarus to Gagarin, to various scientists and cosmonauts. I look into people’s faces: such a mix! Darker, lighter, Caucasian, Mongolian, Pashtun-like, and everything in-between. The history of this region is written on these faces. We of course do not know how different appearances translate into social positions and the local ideas of beauty. Not too many scarfs on women’s heads and those we see are more of a fashion statement than a cover. Like in Istanbul a few years ago, women enhance their profile by piling up hair on the top (or some other material) under the scarfs. The men are slender and narrow-hipped and all wear freshly ironed immaculately white shirts and black or navy trousers, occasionally a tie. This must be the standard office attire. Women in the Metro stop and ask if we need help, twice in English once in French. I engage briefly in a conversation with a French speaking cultured lady, tell her how I learned Russian, and where we live. So good to be able to speak their language.

We are heading for a mosque relatively close to the Chorsu street market, but the distances are much greater than we thought. At a certain point we change our mind and decide to walk to the Chorsu market first. By now it is noon and very hot. We walk along another highway-like street, hugging a large park on our left. These enormous streets from a strange landscape. There are plenty of cars moving fast but it does not feel like the developing world roads: no honking, no traffic jams, drivers stay in their lanes and observe traffic rules, including stopping for pedestrians, no trash.

I obsessively read signs. It is a forever a surprising experience. Some are in Russian, some are in Uzbeki. But the Uzbeki words are sometimes written in Cyrillic letters and sometimes in Roman alphabet. So when I sound out the Russian writing I don’t always understand what I just read. But it is a lot of fun to be able to read Russian signs.

Nothing very interesting at this end of the bazar: mostly clothes and household items, probably Chinese imports. In the early afternoon we rest at a small café under an umbrella. Russian is spoken here and there is no written menu. Philip sips coffee and I order soup. I could easily subsist here on these thick soups, which arrive with a basket of bread.

It is very hot now so we get out of the market. Visit briefly the charming Kukeldash madrasah and the huge modern Juma mosque, with the mosaic and the wood carving we also see on upscale houses. By chance we find a connection between the mosque and the old town. The neighborhood looks dilapidated but at least it represents the history of Tashkent. On the outer edge we see signs of gentrification: one alley features large villas. In a few years we will see the old town converted to all villas, just like the old hutongs in Beijing, with all these BMW and Mercedes’s parked in front. Philip’s only memory of Tashkent from 23 years ago is the metros and blazing heat. He does remember the local market but not as large as the one we saw today.

We take a “taxi” (in reality a private car) to another famous mosque — the Hazroti Imam Friday mosque – and make another stop at a café, this time with a beautiful water fountain falling in a ring of fine droplets. The negotiations with the drivers are interesting: when a man whom we accost is not going toward our destination he stops another car and arranges for a ride for us. So nice! But the price we negotiate ourselves. We spent a total of $8 on all the rides and cafes!

An afternoon rest in the hotel’s garden with a glass of beer. Halina tries to understand the Russian conversation of the people at the next table. We are both pretty tired so we read and Philip naps in his chair. A little later we walk our street again, looking for a place to eat. This area, which yesterday evening looked like a wasteland, is teeming with restaurants of all stripes. After dinner we walk some more. It turns out that our neighborhood is very close to what was once a Jewish Quarter, with Tashkent synagogue at its center. We want to locate it. On the way we pass a huge construction site. The drawings on the fence and the signs proclaim that this will be a complex of luxury towers. The GPS tells us to turn right into a dark alley adjacent to the construction site. We find the small synagogue there and behind the fence we see a large sukkah. In front of the fence stands a huge metal menorah, maybe 25 feet tall.

It is clear that the synagogue, along with this entire alley and people living here, will soon disappear under the pressure of the growing housing complex. The construction will only accelerate the process that has been under way for decades: the end of the Jewish community in Tashkent. I wonder if my parents, the communists, had any contact with this Jewish community (at that time numbering several hundred thousands) during the war years. My guess is they did not. What a pity that I did not travel to Uzbekistan when Tata was still alive. So many unanswered questions!

Our walk back takes us along high end shops and restaurants and through dilapidated neighborhoods with semi-high rise flats. There are enough people in these streets to feel safe, but it is not pretty. We try to locate the Center of Lubavichim but eventually give up and head for the hotel, very very tired.

Traveling to Khiva. Wednesday, October 3.

After a slow morning we head to the airport for a 1 PM flight to Urgench. This airport for domestic flights is quiet and very pleasant. It is an hour-long flight and most of the passengers speak German and British English. A surprise awaits as when we discover that two men are holding signs with Philip’s name on them. Apparently, Philip mistakenly arranged a pickup with both the hotel and the travel agent. The two men are very agitated while the security guard asks us to choose between them. Solomonian choice. We solve the problem by paying the hotel fellow $10 for his trouble and go with the other guy. He gives us a wide smile sporting several gold front teeth. It takes over half an hour of fast driving to arrive at Khiva. We pass fields of recently harvested cotton plants, which we see for the first time. The landscape is completely flat.

Hotel Scheherazade us lovely. Not very big – maybe 20 rooms – with an intimate family atmosphere, comfortable inviting armchairs scattered with abundance, beautiful wooden carvings everywhere, and old fashioned parquet floors, including our room. Despite the intense heat outside it is cool in the interior without air-conditioning. The reception desk attendant serves us tea with cakes, then we unpack, rest, and go out to explore the neighborhood. Our hotel is within the city walls but not in the very center of the old town, in a regular neighborhood with kids playing outside. Just as we like it.

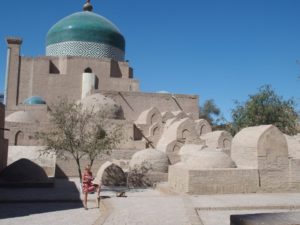

Khiva is magical. It is a well preserved Muslim town, full of madrassas, mosques, living quarters and shops, all encircled by ancient walls. The renovations of the past twenty years “sanitized” it and tourism turned it into a bazar designed strictly for tourist consumption. But despite all that, and the large numbers of tourists, it still shines with great beauty and allows one to imagine what life might have looked like here centuries ago. Today we only take a quick look, leaving a deeper exploration for tomorrow. One thing that strikes me is the sandy colors of buildings, walls, and the landscape. They are all monochromatically beige. The bricks used for construction are the same material as those I saw in the Turfan area of Northwest China two decades ago. They are made of the clay in this desert and dried in the sun. The beige background provides a striking contrast for the colorful (dominated by blue) tiles on structures.

We have dinner on a rooftop while admiring the incredible light of the setting sun reflected from the buildings. We chat for a bit with a Swiss couple at the next table. They are at the end of a two week trip while ours has just began. After dinner we wander some more, have coffee and tea at a simple place for the locals right outside the main gate, and promptly get lost on the way to the hotel. As soon as we move away from the very center of the old town, where all the tourists linger, we find ourselves in a maze of alleys, pitch dark, convoluted, and deserted. The only light we detect is that escaping the closed doors and tightly shuttered windows of the usual family dwellings: blind walls to the outside. We actually find ourselves between two tall walls, with no clear way out. Finally we find a woman with two infants sitting on her front steps and, after admiring the twins on her lap, I ask her for directions to our hotel. She promptly calls her two older daughters, who lead us home, using, in this medieval place, a mobile phone as a flashlight. In the last minute I suddenly remember the marker and paint sets I brought with me in case some children need presents. With joy I hand them to the girls and they joyfully accept.

Khiva. Thursday, October 4

Khiva was a minor point on the Silk until the 16th century when Timor’s empire was already disintegrating and a tribe of Uzbeks settled this land and created the state of Kherezm, with Khiva as its capital and the seat of the Khan. In the early 18th century Khiva’s Khan turned to Peter the Great for protection against various local invaders but by the time Peter sent his 4000 troops the Khan changed his mind and found them to be a threat. He simply slaughter them all, to the last man. But that freedom did not last long. During the 18th century Persians moved in and in the second half of the 19th century Russian conquered Khiva. In 1924 the Soviets incorporated Khiva into the newly created Uzbekistan Socialist Republic. The economy of Khiva’s Khanate was thriving for three centuries on its famous slave market, until the 18th or 19th century. As the day progresses we discover that the most beautiful of beautiful structures we admire in Khiva date to the period of 17th to 20th centuries, though it feels more like coming from the 10-11th centuries.

Over this morning’s breakfast we have an interesting conversation with two Californian travelers, she originally from Italy. It is apparent that they are both academics. We talk about the drought in S. California, very appropriate in this desert town where the water is being drained for the cotton monoculture, started by the Soviet Union.

The light here is very bright, even in October. And the morning is cool. We walk in the bright sunlight between the adobe houses until we suddenly enter the tourist area through a narrow opening (no surprise we missed it last night in the darkness). Our first stop is the currency exchange office. The previous day this failed because she only had small banknotes; today we had first to wait patiently (she was sweeping the dust in front to the office) and when she finally opened she still had only bills of 5000 and some 10,000. For our $100 we get stacks of bills (one US$ converts to about 10,000 Som).

Our first sight is the mighty “Kuhna Ark” which is a palace in a palace, with stunning open spaces with highly decorated ceilings and adorned with blue-glazed tiles in fantastic varieties. We then visit the Museum of applied art, with silk money, beautiful wood carvings, an impressive throne, among others. We also visit the museum of history with lots of old photographs; and a very interesting mausoleum, dotted with graves with a very special form. These sites are all in a very close proximity to each other and not very big.

We meandered somewhat from site to site, without exactly knowing what we are seeing and how to interpret it in the context of culture and history. We discuss between us if we should hire a guide, which solves some of these problems but creates others (such as becoming passive, and missing adventure and excitement). After lunch and another visit to a madrasah featuring more than 200 wood-carved pillars we get back to the hotel and sleep for nearly two hours.

Around 4 pm we hit the road again, this time heading for the Tosh-Havli palace. But first we retrace our steps of the previous dark night’s wanderings, along the inner side of the southern wall. We locate the field of graves we saw in the dark last night, built against the massive city walls at least 20 meters high maybe 5 meters thick. Back in the touristy part of town Halina negotiates 3 scarves made of camel wool and as transparent as lace. The women of Khiva dress beautifully and walk very straight. The fashion is velvet dresses in deep colors, decorated with embroidery and glitter. They put their thick shiny black hair in pony tails or pile them up on top, with lovely results. So pretty.

The Tosh-Havli palace is enormous, beautifully decorated with blue tiles and impressive ceilings. We move through a labyrinth of rooms, with here and there a sudden unexpected courtyard, completely deserted at this time, except for a few vendors of handmade goods. Khiva is overrun by tourists, but they are almost all congregated in the very center of the old town and in a few most famous buildings. So it is easy to find solitude.

What is amazing about Khiva is that some of the palaces here were built as recently as first decades of the 20th century. And the art is the same as can be encountered in the south of Spain, built by the Moors in the 12th-15th centuries, or as other masterpieces of Islam dating centuries earlier. It seems that the history of the rest of the world passed by this place with little trace. While Europe and Far and Middle East were shaking with revolutions, changing regimes, the Great War, collapses of empires, redrawing the world map, Marxism and the Soviet revolution, the people of this land went about their lives far removed from all this commotion. The great game between Russia, Ottoman Empire and Great Brittan was partly played here but without major impacts on the local live. Until the invasion by the Soviets in 1920 Khiva was ruled by its Khans and the rest of the world was not so important. In fact, it was only in 1924, when the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan was created, that the borders were demarcated and a national identity generated. If it was not for enforced collectivization of agriculture, the imposed cotton monoculture, and the Stalinist purges, this region would have sailed through the Soviet period without much disturbance.

The Soviets also brought their language and alphabet (and almost 100% literacy). Until then, Uzbekis used the Arabic alphabet, introduced here together with Islam in the 8th century. In the 20th century they switched to Cyrillic alphabet and started writing from left to right, and in the 21st century they adopted Latin alphabet. Amazing!

And who are Uzbeks? First, the Alexander the Great came in 4th century BC and took this region away from the Persian Empire. But did not leave many traces. Turkic tribes settled here in the 6th century. The Arabs came in the 8th century and left behind Islam and Arabic alphabet, but did not stay otherwise. In the 9th and 10th centuries Persians came back to this region and made Bukhara the capital. That was followed by Genghis Khan and the Mongolian invaders in the13th century, followed by the great rule of a native son Timur who made Samarkand his capital. Uzbeks are descendants of all these winds blowing through this land, especially the Turks, Persians and Mongolians.

As the sun is setting we have a beer at a deserted kebab-place, and find a nice, sheltered, quiet, low-key restaurant. Halina reads from the guidebook about the history of Uzbekistan and how Uzbeks and their modern nation emerged. In the dark we find our way to the hotel easily, and spent the rest of the evening catching up with email and writing.

Vicinity of Khiva. Friday October 5.

This day is different from the others: at 9am a driver and guide meet us at the hotel for a day trip to Toprak Kala and Kizyl Kala. Both are old cities from the 2nd century, established by Zoroastrians, but they are quite different.

We drove through Urgench and through agricultural land, mostly cotton, into a desert landscape. We learned that cotton is picked four times between middle of September and end of October. Before each harvest the land is irrigated, which prompts the fully developed flowers to open and release their cotton. We stopped the car to take a closer look at the plants. Cotton in this raw state looks like cotton balls sold in drugstores: snowy white and delicate. Halina took a branch with her as a souvenir.

We also drove under unfinished railway overpass, which was supposed to be connected to this highway. The project was never completed and now it stands as a monument to corruption. After about 2 hours of driving we arrived at Toprak Kala. This settlement was built almost two millennia ago out of mud bricks and adobe finish. It is amazing that so much of it still stands under this heat and wind. It was one of 50 similar settlements of a few hundred people, placed in such distance from each other that if one was attacked it could notify the other by lighting a big fire on this flat land. This settlement was abandoned when the inhabitants moved closer to the water source. All the interesting artefacts were unfortunately sent to the museums in Moscow and Petersburg.

We next drove to Kizul Kala, which is nearby as the bird flies, but for us required a huge detour. First we saw a Zoroastrian temple and then we took a sandy path steeply upwards to the top of the mud walls of a huge city. We could actually walk over the walls around the city; the walls had all kind of constructions like arches and tunnels, and the landscape reminded us of Monument Valley in Utah or Arizona. The digging for the mud to construct this city created a nearby lake that looked pretty large to us. The guide stayed behind but we both walked around the entire perimeter of the town, which was destroyed by an invasion. The guide told us a complicated legend surrounding that story. A slave boy became a General and wanted to marry a highly born girl, but she refused him because of his low origin. The General was furious and commanded his army to attack and rape the girl. The Khan did not tolerate this and attacked the General’s army. The general was captured was hanged in the middle of this city.

After the hike we started back to Khiva. It became clear that the guide did not plan on stopping for lunch and altogether behaved like he wanted to drop us off at the hotel as soon as possible. So we asked him to take us to lunch in some village on the way. His idea of local was a horrific restaurant/bowling alley in Urgench with glitzy decorations, stroboscopic light inside, awful music and not a human being inside. We were served dreadful over-salted grilled chicken wing kebabs and stale bread. Only the borscht Halina ordered was good. We drove back to Khiva, where the guide left the car early so left it to the driver to drop us off at the hotel. Hopefully we will never see this guy again.

By then it was close to 4pm. Halina fell immediately asleep while Philip hit the road again; he wanted to get a feel for Khiva as a whole, without distraction by all the tourist sites. He took pictures of laundry against the backdrop of a mosque, and of city life like a bunch of kittens warming on a stone, and the adobe houses and their inhabitants. On the way to the North Gate he hit a ceremony in a narrow street: two women were bowing, one was completely covered, music playing, a man talking in a loudspeaker, and a large crowd around. He could not figure out what was happening, and nobody could explain it to him. He climbed the city wall and walked a little there, then went back to fetch Halina who was just up and ready to go out. We made roughly the same trip again, and Halina made a larger walk on the top of the city walls. We then headed to our favorite Terrace restaurant with a view over the entire old city. The setting of the sun was beautiful but somewhat clouded through the upcoming change of weather. We enjoyed the company of an eccentric Englishman who was in need of people to listen to his travel and language stories; first it was another couple who was leaving, then us; and later a poor single Japanese man who was seated at his table.

Traveling to Bukhara. Saturday October 6

Today we are traveling from Khiva to Bukhara, which should take 6-7 hours. We were taken aback to hear that we had to pay our hotel in cash; we had not counted on that. Although we had sufficient USD to pay the hotel, if all the future hotels require cash we will not have enough. And this is Saturday, the banks closed for the next two days.

A different driver showed up with a better car than yesterday. After the hot several days today the temperature suddenly dropped to the 60ies and cloudy. The driver drove fast, partially the same route as the previous day, then turned to the SE towards the desert. The road is a superb 4 lane highway with hardly any traffic. The flat monotonous landscape became desolate after the agriculture and houses disappeared. After about a hundred kilometers we entered a desert: sand, tiny shrubs, dust everywhere. Very rarely a house along the highway or an oil rig. Once we stopped for a toilet, not even coffee was available. At some point it started raining: a rare event in these parts. The monotony of the landscape put us into a sleepy mood so we napped on and off. Around 1pm the road suddenly became bad; the driver had to swerve a lot around holes and sometimes drove in the border. The traffic became more intense. Around 3 pm we reached Bukhara.

The driver parked the car in the center and walked with us to the hotel, which was in a maze of streets but quite reachable by car. The boutique hotel is quite nice with multiple courtyards; our room is spacious with a couch and two tables. We were really tired from the trip but Philip wanted to revisit Lyabi-Hauz, the pond overshadowed by century-old mulberry trees that are as old as the pond, end 15th century. He remembered sitting there with Joris 23 years ago in a 48 degree centigrade day, waiting for the heat to subside. We ate grilled chicken and washed it with beer at the outdoor restaurant overlooking the pond. The place had still some of the atmosphere Philip remembered but much has been modernized and “sanitized”.

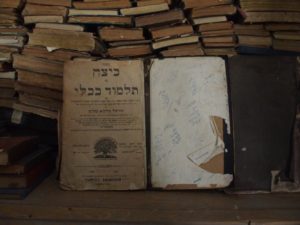

We went out again searching for the famous Bukhara Synagogue, which we found in one of the alleys. At the time of the Soviet takeover there were 25,000 Sephardic Jews living here but over the decades this number melted down to about 500 today. But there is a thriving Jewish school for several hundred children, only about thirty of whom are Jewish. For the rest of the children this is a form of high quality international school. The Rabbi-Cantor-caretaker (all in one person) is an exuberant figure who entertained us with stories about all the dignitaries that had visited the place. The discussion was entirely in Russian, and Philip was impressed by Halina’s language skills although he himself understood just a few words.

The big draw is an ancient Tora, which dates back to the Babylonian exile and traveled with the Jews to Persia, then Iraq and eventually to Bukhara. Nobody knows its age but it may be as much as 3000 years. It is written on deer skin and is in excellent condition. Hilary Clinton was here, she turns out to be ¼ Jewish; Madelyn Albright, president Karimov and the Attorney-general of Uzbekistan, and many others. The rabbi also told us that Hilary wanted to find out something about her Jewish grandmother, who apparently spent the war years in Uzbekistan. Despite many efforts nothing was found. That put to rest any hopes Halina might have still had about finding and trace of her parents.

From the perspective of historical chronology this trip progresses backward. Khiva has established itself as a cultural center much more recently than Bukhara and Samarkand. Khiva’s greatest flourishing took place in the 17-19 centuries and into the early 20th century; Bukhara’s greatest flourishing took place in the 8-10th century, and to a smaller degree during the 16-18th century. And Samarkand had it renaissance during the reign of Timur and his descendant, in the 14th and 15th centuries. But this order of seeing things makes sense from another perspective: we are moving from smaller and intimate to larger and more spectacular. Furthermore, as we discovered, one cannot talk about the history of Uzbekistan because this country is a creation of the Soviets in the 1920s. Rather, it is a history of separate cities-Khanates staged against the great empires that met in this region: Persia, Mongols, Russia, England, and the Great game of the 19th century.

Bukhara. Sunday, October 7

Today we sightsee Bukhara under the guidance of our charming 24 years old guide Munisa.

The great artistic and intellectual renaissance in Bukhara took place in the 10th and 11th centuries when it was the capital of the Samanide kingdom. The Mongol invasion in the 13th century put an end to it and the decline continued under Timur (Tamerlane) who made Samarkand his capital in the 14th century. Bukhara had its second renaissance in the period of the 16th to 18th century under the Persian domination. That came to an end in 1868 when Russia conquered Bukhara, Samarkand and Khiva. Under Tsarist Russia not much changed in this region: the Emirs (successors of the Khans) continued their rule and the social institutions continued as well. But when the Soviets came in 1920 and Bukhara became part of the Socialist Uzbeki Republic, everything radically changed. The last Emir of Bukhara barely escaped to Afghanistan and his entire family, which traveled separately, was captured and killed.

Munisa, 24 years young and quite accomplished, turned out to be a great guide and won an international oratory contest for a reason: she is lively, intelligent, and a great story teller (see above). She starts the tour by taking us to a puppet maker shop at the beginning of our alley, where we observe how puppets were made; and of course we get a demonstration by one of the owners. We walk along the Lyaby Hauz, the pond that we visited yesterday, along the statue of Hoja Nasruddin, the “wise-fool”, to the first covered market — the money exchange market — which is a dome with several little shops underneath. We continue our walk, visiting various arts and crafts shops, through the second covered market, which began its life as the hat-makers market. We see women embroidering, a man chiseling a copper plate, and a carpet factory with a dazzling display of most beautiful carpets. We also watch carpets being made by young women. Munisa told us that the training of how to make carpets takes only three days. But of course she referred to the use of the tool, which looks like a crocheting needle. The selection of colors and the patterns are the skills that take much longer. In this factory the girls are given the patterns drawn on a large piece of paper in black pen and the choice of colors is left to them. We finger the silk threads in brilliant colors used for the carpets, all the dyes extracted from plants: pomegranate fruit and skin, onion skin, saffron, carrot, indigo, and so on. All but indigo, which is imported, are produced locally.

Through the morning we visit various amazing madrasahs and mosques. One of them is in reds and pinks, the colors not officially allowed in Islam but the khan or emir defied tradition and did it anyway. Halina buys a shawl of pure silk with Uzbeki pattern, and Philip cannot not resist a pair of scissors in the form of a bird.

We look at the impressive Kalon minaret, the highest of Uzbekistan, with a beautiful legend of how the foundation was made (milk, honey and egg yolk?).

Over lunch we talk with Munisa about life in Uzbekistan, especially the difference between the Soviet era and the post-independence period. She notes that, in addition to establishing strong education and healthcare systems, the greatest achievement of the Soviet era was to liberate women, throw away their veils, and make them equal to men in the eyes of the law. We look at this self-possessed confident young woman as the embodiment of this radical social change. Who knows, perhaps if the Soviet Union succeeded with its invasion of Afghanistan the Afghan women would have very different lives today. We also learn that “true” Bukharans speak a language most similar to the Tajik language, which derives from Farsi in Iran. It is very different from the Uzbeki language. It is ironic that people here use the term “after independence’ when referring to the post-Soviet period, maybe forgetting that it was the Soviet Union that drew a line on the map and called it Uzbekistan, thus creating a national identity and pride. It reminds me of Ukraine and Belarus, which did not exist as nation-states until they became soviet republics. And now they all talk about independence, national pride and identity. Their adversary created them.

After lunch we take coffee at the famous Silk Road Tea House, which serves Turkish coffee with a nice assortments of Turkish sweets. In the afternoon we visit the fortress/castle called the Ark, the origins of which go back to the 6th century B.C., with many additions over the years. It is impossible to describe each place we have seen today. And that is not the point. The overall impressions is that of splendor and serenity of these structures. What strikes me about this old city as well as that in Khiva is the total absence of any connection to nature. The buildings and their plazas are an uninterrupted surface of stones. Even the splendid decorations are, in the Islamic style, devoid of any images of animals or trees. It is all so abstract and geometric. God is not to be found in nature. God is in people’s minds and hearts.

In the midafternoon we say goodbye to our lovely guide and throw ourselves on the beds in the hotel room. Before dinner we walk some more, retracing our steps and taking in the old city and understanding more of the structure and the lay-out, and refreshing our memories of what we had already seen. We even revisit the carpet shop, but when we see a very large group of Italian tourists, haggard from the day of sightseeing, we quickly leave. At dinner we share a table with a quiet Japanese businessmen traveling alone but unfortunately his English is too limited to have a satisfying conversation. All we get from him is that he is worried about Trump’s tariffs on imported goods and that young Japanese do not get married because they do not feel financially secure. This was a long and tiring day, and I feel that the cold I caught on the plane to Tashkent is getting worse.

Monday, October 8, Bukhara and vicinity.

We meet a lot of tourists on this trip, all concentrated in a relatively confined part of each city, and almost all of them look like they are in their seventies. This is a grand geriatric pilgrimage of people checking things off from their bucket lists. We are part of that, of course. But it is really bizarre to be surrounded almost exclusively by the elderly, mostly looking rather tired and unkempt in their comfortable and dreary clothes and shoes. It would be more fun to blend with a mixed crowd of locals and tourists of all ages and styles.

This morning Halina’s cough is worse than ever and she is prepared to skip today’s excursion. However, when the new guide, Fira, a nice woman in her early 30s, appears she is quickly persuaded that today was mostly driving and not walking, and that she should come. On the way, Halina buys some cough medication in a drugstore (an extract from leaves of ivy plant).

In the beginning there is some confusion because the travel agency provided us with a guide but not transportation, while most of today’s sites are out of town. In order to avoid fuss we agree to pay for an inexpensive taxi instead but it is indicative of a somewhat sloppy management by the agency. The guide is nice but more “guide-like” than Munisa yesterday. Our first stop is outside Bukhara, a memorial complex of Hazrati Bakhouddin Naqshbandi, a Sufi scholar and teacher who lived and taught in the early 20th century in Bukhara. Sufi is a more meditative, gentle, and philosophical than the two traditional branches of Islam, and we think more peaceful. Hazrati created this enormous complex but after his death it was disbanded; it is now under restoration. The ceilings are beautiful and the whole place is peaceful and here and there shaded by trees.

The taxi driver who drives like a madman and at a certain moment also starts to work on his email while driving (until Philip asked him sharply to stop) brings us safely but shaken to our next destination: The Chor-Bakr Necropolis, situated in another “village” which was reached by racing along an 8 lane highway. The necropolis was also under restoration and contained a number of interesting graves. The third stop, after another near-deadly car-race, was the summer residence of the last emir of Bukhara, early 20th century, the Sitora-i-Mokhti Khosa. The palace was an interesting mix of European and middle-Asian building styles. Poor Emir, he built it in 1913 and by 1920 had to run to Afghanistan to save his life. Did not get to enjoy it much.

The final stop is inside Bukhara: the Tchor Minor, which means Four Minarets, a mosque with four minarets which we quickly view from the outside because we cannot get in. Here we say good bye to the taxi driver and the guide. By now Philip is the one who is tired of all the mosques and sites, and of the tourist groups and merchandise. We find a place for lunch where freshly ironed table cloths make a lot of promises but in reality the beer is warm, the soup is cold, and the bread is stale.

By now we can easily navigate the restaurant menus, which do not different much from one restaurant to another. My favorite in Khiva was green handmade spinach noodles, with a beef goulash on top. In Bukhara my favorite is Monti, the steamed dumplings with filling, which is usually beef but also pumpkin and vegetables. It is very similar to Japanese gyoza dumplings. The dough is very delicate. Tandyr somsa is good also; it is dough filled with meat and other things and baked in a clay oven “tandyr” until it looks like baked bread. Palmeli is also good, a soup with meatballs. In general, their soups are very good, often served as creamed purees, or as thick goulash-like creations. And there are the Russian familiar soups: solyanka, vegetable, and borsch in Ukrainian style (with cabbage, tomatoes, potatoes and some other veggies). And of course there is the king of all dishes: plov: white rice cooked with vegetables, spices, and meat. I saw a man cooking plov in Tashkent in a huge cauldron. He used lamb meet and there was so much fat at the bottom of the vessel that it totally turned me off. But Bukharin plov is different. It uses lean beef and steams rice and vegetables separately, combining with been only in the last step. It is delicious.

And of course there are these splendid salads in an endless variety, and fruits, which we do not touch in fear for getting food poisoning.

We decide to take the afternoon off and go back to our hotel. Halina takes her new medicine and falls asleep over her book. Philip is tired, irritated and bored, even by his book; he later went for a walk alone which brought him after walking some back street eventually to the Silk Road coffee and tea shop, which our yesterday guide had discovered for us. Walking and two cups of strong Turkish coffee, one with cinnamon and one with cardamom, and the trays of sweets did the trick: he felt better and returned to the hotel, where Halina was also feeling better after some nice sleep and relaxation.

After dinner at the same Chinor restaurant as the previous evening we walk to Silk Road café where we share a pot of strong ginger tea. Afterwards we walked over and admired the beautifully illuminated Kalon minaret. We also buy half a liter of vodka in anticipation of a cold night in a yurt, tomorrow. This was our last night I Bukhara and it seems that we got over the low point of our trip.

Bukhara to Yurt, Tuesday, October 9.

We wake up to heavy sky and light rain. Check out of the hotel. Halina is feeling much better after a good sleep without coughing, this medicine is great. Today we have only a driver, no guide, which is fine as we get tired of guides rather quickly. The driver’s name Bekir. He is in his twenties, exudes warmth, has a spark in his eyes, and speak no English. This is Halina’s day when she needs to navigate in Russian the whole day. We are heading to the night in a yurt, somewhere out there.

The drive through the desert is familiar by now. The flat land that extends way out beyond the horizon, and the big sky follows it. At some point we notice mountains on the horizon, the first such sight since we came to this country. After maybe two hours we stop at a celebrated ceramic workshop and museum, where a young woman gives us a tour of the place. We learn about the different styles of ceramics over the ages and across different regions here. These ceramics are primarily in earth colors and are beautiful. On the wall there are pictures of luminaries who visited here, including Albright and Hillary Clinton. The guide tells us that they are a seventh generation of ceramic makers in one family and that the early soviet period was the hardest to survive because the authorities aimed to eliminate all private enterprise and have everybody become factory workers. Her father, who is in charge of the place, speaks fluent English and French and is dressed like American cowboy. We buy a few small items for gifts.

Another stretch of driving and we stop at a historical sight corresponding to a truck stop, only for caravans. In one round structure with a dome there is a water cistern fed by melting snow, rain, and water brought by clay pipes from the distant mountains. Across the road from the cistern there used to be a fort of sorts where camels ate and rested, or if needed were replaced, people could do ablutions in the baths, pray, eat and sleep. We encounter an American couple from D.C. (one of the few American tourists here) who are following the same exact itinerary as we do. They have a good guide with them and so we benefit from it.

It is almost 2 o’clock when we stop for lunch at a private house in a village. Once we enter we recognize our German neighbors from the Hotel in Bukhara and the American couple. The German woman speaks fluent Russian. The lunch is served outdoors on a patio next to a luscious garden. They serve is many types of salads, which I recognize as similar to Russian and Polish surowki’ and the local kind of very thick kefir, a relative of what we know as Greek yogurt. Then a vegetable soup, and finally for the main course Moti with meat and pumpkin. The food is divine, exactly my kind.

We are again on the road, again through a desert. This road has been built exactly following the ancient caravan road from China to Europe, the great Silk Road. It is so straight and uneventful that I count only two turns (both right) since we left Bukhara. But at some point the landscape changes: it becomes undulating, there are mountains on the horizon. One more stop – at the ruins of a fortress that some claim to have been built by Alexander the Great and others question it – and we turn into a dirt road which brings us to the destination. The yurt camp is not full, probably because the temperature has dropped precipitously. This is the coldest day of our entire trip and the night should bring us to a freezing point. The good news is that we get a yurt with four beds all to ourselves. There are plenty of covers for the night.

It is close the six o’clock and soon the sun will set so we go straight for the camel rides before it is too late. The rides are real fun if uneventful. The four of us following each other. My camel is last, which gives me a sorry opportunity to watch the other camels defecate and get their backs and rear legs covered in excrement. The ride is a lot of fun. The setting sun and the silence of this remote spot is amazing. We are really in Central Asia, following the Silk Road!

Dinner turns out to be the highlight of the day. There are four tables: one speaks English – us and the other US couple – one speaks Latvian, one speaks German and one speaks Uzbeki (guides and drivers). The food resembles that at lunch except that the main course is stuffed green peppers. They serve us this marvelous selection of vegetable salads, some fresh, some roasted, some pickled. I could eat that stuff three times a day, so we throw our caution about fresh vegetables to the wind and go for it. Each table has a carafe of vodka and carafe of red wine. And they quickly get consumed. I love this food. The atmosphere is festive. And then, a Khazaki singer shows up, wearing a splendid purple jacket and skull cap, and sings to us songs while accompanying on a string instrument, the name of which I do not remember. Looks like a lute. These songs are like ballads, have so many words. He has a rich wonderful voice and a classic look of his tribe: swarthy skin, a round face with high cheekbones, small nose and mouth, and narrow slanted eyes. One of the guides is a vivacious party-loving character, determined to get the party going comes to our table and tries to get Philip, then the other fellow, to a dance floor, unsuccessfully. So I get up and go. And we dance! I follow his movements, which are probably just for men, but that is all I know. Within minutes everybody gets up and we have a real dancing party. So joyful. At the end, the hat gets passed around for some donations.

This concert brings me close to my parents. I can now imagine their evenings in Uzbekistan during WWII, listening to these songs and feeling joy, despite the famine and all the other horrors of war. Oh, why didn’t I go to Uzbekistan ten years ago, when I could have talked with Tata about it?

We go for a walk in the darkness, gazing at the stars, and in this total silence of the nighttime desert, locating the big dipper which is much lower in the sky than on Cape Cod. After the vodka and the dancing the cold does not seem so bad. This was such a great day.

From Yurt to Samarkand, Wednesday, October 10

After about three hours of traveling, looking out of the window, dozing off, and chatting a little, we reach the village of Mistan, where we will lunch in a local home.

The lady of the house, a woman in her 30s or 40s, welcomes the women with a kisses on both cheeks. She has a broad smile and several gold teeth, which in Uzbekistan’s rural regions is a fashion statement, at least among her generation. We are led to an inner court with a vegetable garden and a sumptuous two tables set for lunch, where we are greeted by an elderly owner, and the second daughter and her two small children. This house belongs to this 83 year old patriarch, a Hadji, which is a title bestowed on someone who made a pilgrimage to Mecca. He really looks like a hadji: tall, straight, with a long white beard and a graceful demeanor. At this same time Mr. Hadji (as everybody in our company calls him) is very outgoing, shakes hands with each of us, and is interested in a conversation. The German lady from our hotel in Bukhara is here, speaking her enviably fluent Russian, and she gets immediately engaged with Mr. Hadji.

Before sitting down we watch the mother make plov in a large cauldron shaped like a wok, heated on a wood burning stove. We also help bake the flat Uzbeki bread. The bread bakes in a round-bellied wood-burning oven with a wide opening at the top, through which the flat pancakes of dough (stuffed with pumpkin) get introduced. This oven is called “tandyr”. Wearing a large glove made most likely from asbestos Halina glues the dough pancake to side wall until it stick. When ready (about ten minutes), the bread falls off to the bottom.

We learn some things about Uzbeki families. For example, the youngest son inherits the house and its content from the parents, and in exchange is responsible for all maintenance costs, taxes, etc. as well as the care for the parents until their death. The Hadji’s wife died a few months ago and we think that now the youngest son runs this household, but they live elsewhere in the village. There are 6 children and each has 6 children, and all live in this village.

The lunch is superb while Mr. Hadji keeps refiling our glasses with vodka and red wine. Afterward, we get a tour of the house and the stable with several goats (the cows were outside) and learn that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when all the banks failed, they keep their savings in cash in dollars. They also showed us the folded comforters, mostly hand embroidered, stacked up in two piles form floor to ceiling. These comforters get unfolded for sitting and sleeping.

After some more driving we enter Samarkand. The city is not as big as Tashkent, but much bigger than Bukhara, and our hotel turned out to be in an alley close to the crossing of two wide multi-lane boulevards, not unlike hotel Gloria in Tashkent. The hotel itself is lovely with a spacious room and a super-helpful manager. Quite a difference from a yurt and we both are happy to be back in civilization again and to take a warm shower and change to clean clothes. In the evening we take a look at this city by walking about 15 minutes to the recommended hotel Oasis Garden. We run for our lives every time we cross a street. In this city the stopping lights for pedestrians turn red the very moment when the cars get the green lights; and these cars know how to accelerate and race and scare the pedestrians.

Oasis is like an oasis: a luxurious and calm. We sit in large low armchairs next to low tables, which makes eating rather uncomfortable. There are several functions going on here, in the private dining rooms and the large function rooms, so we get to see a parade of the Samarkand society dressed in their best evening clothes. After dinner we take a taxi to the Registan: the plaza where three gigantic madrasahs are facing each other. This is the most famous place in central Asia and probably the most beautiful spot in the Islamic world. At night it is fully illuminated and magical. We explore the walls of one of the madrasahs by walking around it, taking a close look at the glazed tiles laid out in geometrical patterns. We experiment with taking photos of our shadows on the tiled walls.

Walking back from the Registan to the hotel we see in the distance the illuminated dome of another great mosque. It all looks a bit unreal.

Samarkand, Thursday October 11

Philip had a sleepless night and woke up grumpy, but Halina’s cold is definitely on a retreat. Today is our “free” day without a guide or a driver. The weather is cool and sunny, perfect for exploring the city. We leisurely walk to the Registan. By daylight it looks very different but just as impressive. First we visit the Ulugbek madrasah, on the left side, the oldest and most impressive one. What Philip forgot after 23 years, is that beyond the impressive façade into the courtyard there are three more facades, just as impressive as the first one. This madrasah is two-story high, with the upstairs rooms used in the past as dormitories for students and guestrooms for pilgrims. The beauty of these buildings is overwhelming and cannot be detracted by all the vendors. In fact, I like this bazar-like activity within these monuments because it gives it life in this otherwise outdoor museum. Inside our attention is drawn to an impressive collection of old photos from the 19th and early 20th century. A powerful 19th century earthquake largely destroyed Registan. The old photos from the first decades of the 20th century show the sorry remains of the buildings, surrounded by horse-drawn wagons, people conducting business, life. It is disappointing to think that we are seeing the replicas, but we also acknowledge that during the Soviet period the Russians did a really impressive job restoring it all.

The second madrasah, Tilla Kari, is smaller but also very beautiful. The most impressive is the mosque behind one of the inner courtyard facades, with breathtaking gold-painted inner dome ceiling and very beautiful design. The third madrasah Sher Dor is equally impressive but by now we are saturated and must leave this place. We are searching for the old Jewish Quarter.

The urban planners and government officials responsible for tourism in Uzbekistan have this insane idea that tourists want order and cleanliness (and who knows, maybe many of them do). So they sanitized the place, bulldozed the local markets, nicely paved the streets, installed flower beds, and put up a 20-30 foot wall to separate the section with tourist monuments from the old city. There are a few small doors at certain locations in the wall, which connect these two worlds. We find our door with the help of the guidebook and by asking the tourist information next door.

Crossing through the door is like going through a looking glass: one long step and we are in a world several centuries in the past. The old city is unassuming: low structures along the narrow street, few windows looking into the street, in the typical style of these regions, pavement (where there is one) is cleanly swept, schoolchildren in uniforms pass us by, the aroma of freshly baked bread follows us. Occasionally the front double doors of households open for just long enough to let us see the inner courtyard. Some doors are very ornate and elegant, suggesting much richer households that their anonymous blind exteriors suggest.

A father with two children, a girl 7 and a boy 9 stop because the daughter wants to practice her English. We exchange the usual “where are you from” and “my name is”, “how old are you”. The father notices my Jewish star golden pendant and immediately offers directions to the synagogue.

Sephardic Jews came here from Iraq and Afghanistan more than 2000 years ago. They bought up the land on about a dozen streets and created a community. When we knock on the synagogue’s gate a kindly looking man of 64 opens (people in Uzbekistan often ask for my age and tell me theirs). He takes us around to show the small, simple, and lovely synagogue, which is just a large room. He tells me that he has 3 children and 11 grandchildren in Israel. His place is here. In the 1970s there were 35000 Jews in Samarkand but now there are only 230. They still have a minion of 16 families. They all have children and grandchildren in Israel and America. The grandchildren come to visit. This synagogue was built in the XIX century by a rabbi with an Ashkenazy-sounding name, who donated the money. They have books in a cupboard from all over. In the front of this disorderly pile we see a book printed in Warsaw in the 1800s.

In the conversation in Russian I tell him about my parents spending the war years in the Tashkent area. He is familiar with that story, so we get to reminisce about those years. In 1942 many Ashkenazy Jews came here from Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and other German occupied eastern territories of USSR. The locals welcomed them, tried to help. They were entrepreneurial and industrious people, the caretaker says. They opened businesses and some manufacturing facility, settled down. The locals bought them a little cottage adjacent to this synagogue and turned it into an Ashkenazy Synagogue. It is a simple room now, but they continue carrying for it, repainting, cleaning. They took care of orphaned children. After the war some people stayed and died here, some married local girls and boys, some left. I return in my thoughts to my parents. Being communists, they probably did not want to have much to do with these religious people. How ironic: when the needed help the most they did not turn to their own people because of ideology. I am sure that the story is more complicated than that. Oh, how I wish that I could talk it over with Tata!

On the way out I put money in the donation box.

After lunch in the tourist side of the great wall we walk by one of the most famous mosques, the Bibi Khanym mosque, without stopping because we want to spend our remaining energy on the Mausoleum Shah-i-Zinda. We cross by pedestrian bridge a major highway and saw high up against the hill an enormous cemetery. The mausoleum’s lane is adjacent to the cemetery. The steep long steps preclude the older tourist crowd from coming here. We therefore encounter mostly locals, women dressed in their best, sparkling dresses and headscarves. We see the first woman on this trip with a covered face. There are many mausoleums here of significant people from the past. Some structures are simple, others stunningly decorated. At the highest point of this hill we are led into a room where a cousin of Mohamed is buried. This is the most holly of all the tombs. We enter the small chamber, sit on a bench along the wall along with others, a man intones a short prayer for the dead, people respond. Everyone is welcome: women, infidels.

The afternoon rest in the hotel is barely enough to gives us energy for the evening. We have tickets to a performance of Uzbek dances in historic regional costumes. We find the theater without much problems, walking for about twenty minutes through the University district which is always a pleasure: modern and alive with people. The dancing is mediocre, the choreography uninspired, but the costumes are beautiful. At the theater we meet again our US friends Nancy and (???) from the yurt night, who apparently have the same tour operator. We go to dinner with them in the nearby Platan restaurant: good food, a lot of people, loud music, difficult to carry a conversation. We walk home.

Shakhrisabz, Friday, October 12

Today our destination is Shakhrisabz, the place where Timur (or Tamerlane, or Amir Timor) was born and where he intended to be buried. We drive through pleasant outskirts of Samarkand, south through a landscape with agriculture and poplars coloring in the autumn sun, into undulating hills. This is the Urgutz(?) region. It is a verdant land, full of fruit orchards, corn and vegetable fields. At some point we enter a real mountain landscape, stony and reminiscent of Corsica. We pass small settlements, vacation villas and summer camps for kids. The road becomes a hairpin ribbon cut into the mountainside. At some point a crazy driver suddenly appears in a hairpin curve from behind a truck and drives straight into us. We survive but even Bekir is taken aback. As we approach the top of the mountain we encounter small stands selling local very special type of kababs, but we will not take a chance of eating them.

We reach our destination just before 11am and meet our local guide, a young woman in her early 30s who apparently was a last-minute-stand-in. The intended guide was cancelled at the last moment for reasons unknown to us. She is pleasant but very ignorant and cannot answer any questions that go beyond what she has memorized. In fact, we later discover that she had the most basic facts wrong, such as the belief that President Karimov is still alive (he died in office in 2016). We first visit an impressive building, the Ak-Saray palace, which looks like two gigantic towers (the arch in-between collapsed 200 years ago).

A huge statue of Timur stands in the middle of a grassy field, in what used to be the middle of the palace, the completely sanitized remnants of what used to be ruins, a historic bazar and residential neighborhoods. In place of the bazar and the surrounding neighborhood a park has been installed of a similar austere design as in Samarkand: perfectly geometric stone or brick paths cutting through a lawn where not s single blade of grass is out of place, neat rectangles and circles of flowerbeds, a fountain, and recently planted trees. This place is at least as big as the Washington, D.C. Mall, with the monument at one end and the Timor’s tomb at the other. The remaining two sides have luxury and widely spaced residential buildings, two story high, and some commercial spaces, all identical architecture.

The word that comes to mind is “scalping”. They scalped this land in some misguided belief that tourists will like this clean and perfectly organized space, with the great historic monuments sticking out of the landscape completely out of context and meaning. According to our guidebook the UN was so angry when they found out what happened here that they promptly designated this area as “Endangered International Heritage”.

We walk along the grass, along new low residential houses, towards a few other buildings; among them the Kok-Gumbah mosque, which is impressive because its walls are not decorated with glazed tiles but are painted with geometrical figures. We also visit the tomb of Timur and his sons and a grandson. Timur himself was never buried here because when he unexpectedly died in Samarkand in the middle of winter his body could not be transported to Shakhrisabz through the mountain range, and had to be buried in Samarkand instead. His most important grandson Ulugbek is also buried in Samarkand. The guide tells us that in 1973 a Soviet archeologist Gerasimov opened the supposedly empty vault of Timur and found two skeletons of a man and a woman, whose origins are unknown. This defies the wildest belief so we make a note to check out this story.

Timur is still an enigma to us. He was a great conqueror in the 14th century who considered himself to be related (though indirectly) to Genghis Khan. As not a direct descendant he was not entitled to the title of Khan but instead had a title of Emir. When he died at the dawn of the 15th century his empire included all of Central Asia, southern parts of Turkey, Iraq, Persia, Northern parts of Egypt, including Alexandria, and northern parts of India, including Delhi. In his campaigns in Europe he conquered Georgia and came very close to Moscow and Kiev, and what is now Rumania. Timur gave rise to an Indian dynasty and one of his genealogic descendants built Taj Mahal in India. No wonder he is venerated in Uzbekistan. But the veneration seems out of proportion to the age of this story, by now six hundred years old. We make a note to study this question later.

The most pleasant surprise of this visit is the small courtyard next to the still functioning modest mosque, where three chinar trees, planted by Timur in 1373, are still alive, and sprouting new shoots. Many men are sitting in front of the mosque, chatting and presumably waiting for the 1 PM prayer time. One of the men asks where we are from and when we tell him America, he is clearly impressed. So few Americans visit Uzbekistan that we are a novelty. The most numerous tourist groups we have encountered are: Italians, Germans, Japanese and French. The Chinese and Dutch are much less numerous, and we come at the tail of the distribution.

At the southern end of this field we get picked up by the driver and on the way back we lunch in a very pleasant restaurant, open air under the awnings with vines, where only the locals eat. Our guide talks about her father who was killed not so long ago in a terrible car accident; and whom she adored. It turns out that our driver’s father and her father knew each other.

The trip back is uneventful and somewhat sleepy. We arrive tired at our hotel and are able to catch the last rays of the sun on the roof terrace. We follow a familiar daily ritual of taking a rest, with one difference: we now had some vodka to share. We walk to dinner; the restaurants we selected could not be found, so we end up at the Platan restaurant, where we had such an excellent dinner yesterday. Not surprising it fully booked, but they set up a table for us outside, which is actually very pleasant, away from the loud music inside. We walk back to the hotel through quiet dark streets of Samarkand.

Samarkand, Saturday October 13

Our last day in Samarkand. Our bags are packed when Bekir picks us up at 10 AM. The plan is to see the remaining sights in Samarkand and then at 5:30 to catch the fast train for Tashkent. Our driver doubles up as a guide, which means a day of speaking Russian for Halina. We feel somewhat saturated with sights and do not have high expectations, but we are wrong.

Samarkand as a city makes more sense to us than Bukhara. It is crisscrossed by the same grand boulevards as Tashkent, with 3-4 leans of traffic each way, but the rest of the streets are on a human scale, including the modern buildings that are no more than 4-5 stories high. Cutting into the modern streets are alleys that look like all the other alleys in the developing world cities: dusty, with broken or missing paving, with a lot of temporary-looking fences and walls, peeling paint, and bric-a-brac thrown about. Our hotel is located at one of such alley. Walking in one direction we enter another alley lined with university buildings, full of students and occasional men and women in very conservative dark suits. They must be professors. Walking in another direction we enter a grand boulevard and, by crossing it, a large park. This park is the antithesis of Central Park. It consists of a perfectly geometric network of stone walks crisscrossing green lawns and trimmed with flowers. Very few trees to be seen. They use basil as an ornamental plant. It is allowed to grow to 1-2 feet in height and to bloom. The flowers are deep purple. The aroma of basil fills the air. Altogether, our movement from one neighborhood to another (of course with the help of GPS) is uncomplicated.

Nearby is also a large traffic rotary which opens up at one side to what must be the most elegant avenue in this city. It starts with a large monument of the great Timur. The boulevard’s design resembles Commonwealth Avenue in Boston near Public Garden: a pedestrian median framed by tall handsome trees on both sides, with park benches underneath, and two traffic lanes on both sides. Except that this boulevard is twice as wide as Commonwealth Avenue, and it has two more walking paths on both sides of the median, separated by wide ribbons of lawn. At night soft lights illuminate this boulevard.

But crossing streets is a hazardous sport in this city. The infrequent traffic lights do not last long enough for many very wide streets. And once the light turns red, in a fraction of a second all the cars take off like a pack of wolves at high speed. Since it gets dark here at 6:30 PM, our evening walks turn into runs for life whenever we need to cross a street. Another really dangerous feature of these streets are drainage ditches. These are about one-two feet wide and equally deep cement traps separating sidewalks from car pavements. Some contain running water but most are dry. If we do not watch out every time we cross a street, we can easily break a leg by falling into these ditches. This is a totally unfriendly city for handicapped persons.

Our tour starts with the nearby mausoleum where Timur is buried, together with his famous grandson Ulugbek and a few other family members. A beautiful mausoleum full of gold and at the same time simplicity. Timur’s body was examined recently by archeological experts and authenticated through his injuries (right arm and left leg) and his height (6 feet). Ulugbek’s body was also authenticated because he was beheaded, apparently on the order of his own son. We find a map with the conquests of Timur. We also learn that his son and grandson were both his successors and apparently ruled for 40 years; Timur’s son died two years before his grandson Ulugbek.

Our next stop is the astronomical observatory of Ulugbek. This is a great discovery and one of the highlights of our trip. He built this observatory by digging a deep trench with stairs into a hill, and from there he could study both the position of the sun and the stars. He devised fascinating instruments to monitor the skies; apparently he already knew that the earth was a spherical. The discovery of this place sometime in the late 1960s is in itself a miracle; the writing describing the observatory were translated from Persian into Latin and finally rediscovered in the 20th century (Ulugbek’s “Zij” was written either in Persian or in Turkish, not sure). An expedition started to look for the most likely location of the observatory, based on old descriptions. The museum is fascinating and we go through it twice. We also make a note that we will study the lives and works of both Timur and Ulugbek when we return home.

Ulugbek did not study the rotations of Earth and Sun in relation to each other, leaving that job to Nicholas Copernicus half a century later, but he made a map of the stars and estimated the length of the calendar year with a precision greater than anyone before or after him (about 4 seconds off from the current estimate). He also built a madrassa in Registan, where many mathematicians and astronomers studied. Some contemporary historians of science consider Samarkand to be the astronomy’s center of the world in the 15th century. The museum displays images of other great astronomers of those days, but it is a very puzzling thing: They acknowledge Polish astronomer Jan Geveliy (in Latin Johannes Hevelius) in Gdansk and English astronomer at Oxford University John Greaves, both of whom lived in the 17th century, but do not mention the somewhat earlier astronomers (by several decades) Galileo and Nicholas Copernicus, both of whom lived in the second half of the16th and the first half of the 17th centuries (Ulugbek lived in 1394-1449 and became the emir in 1447). John Greaves was involved in translating Ulugbek’s works into Latin.

One more visit today is the Afrosiab museum, which displays a chamber that was found with murals from the 2nd century; royals and ambassadors and messengers on horses and camels, beautiful birds, all with splendid colors. An audiovisual presentation helps us understand it somewhat and we admire the e-reconstructions.

We make a brief stop at a mausoleum where an 11 foot long leg of some giant St. Daniel is buried. Nothing interesting. And then we go to the impressive modern train station, say goodbye to our lovely driver/guide Bekir (in addition to the usual tip I give him my Russian-English dictionary and a set of paints for his little son). The train is filled to capacity with tourists. The usual languages surround us. Two hours later a man picks us up in Tashkent and takes us to “our” Gloria Hotel. A bowl of soup in the restaurant, a sip of vodka in the room, and a quiet evening.

Tashkent, Sunday October 14

What a difference two weeks make! We left Tashkent in a summer heat and return to cool autumn weather and warm clothes. This is our last day on this trip. We have a long travel ahead, starting with a 2 AM drive to the airport, so we need to conserve energy.

Tashkent feels familiar and friendly, even though we spent here only one day before. We like this city. After a slow and leisurely start, we take a taxi to the Timurid museum to learn more about Timor. The museum was built by president Karimov, the founder of the independent Uzbekistan in 1990. It is not really a museum but rather a monument to the great national hero and modern Uzbeki nationalism. It is large and built in the Soviet style of grand staircases and aggressive decorations. Our guidebook already warned us that most of the original artifacts has been long ago taken to Moscow, St. Petersburg and elsewhere. On the wall at the top of the main stairs are two quotes, in huge letters, from the writings and speeches of President Karimov. One of those explains a lot about the cult of Timur. The quote says something like that: If you want to understand the greatness of this country and the Uzbek people, what this nation and its people are capable of, just look at the accomplishments of Emir Timor. In the 25 years of his presidency Karimov created a sense of nationhood for Uzbekistan (which had never existed as such) and built a strong national pride by skillfully building on the achievements of Timur. Every guide we encountered on this trip spoke enthusiastically about Karimov.

After the museum we walk across the Amir Timur square, a nice park with grass and low trees that used to be a shadowy place with century-old trees where old men played their games of chess. No more. We then take a taxi to a highly recommended department store but very quickly get out of it and instead take a stroll along a park-like lovely street, where we take coffee and tea at and outdoor café. At this time of the day the sun fills us with warmth. An accordion player sits next to us and when Halina gives him money he plays for her old Russian songs which she likes. Many people give him money.

Our last destination is again the Chorsu market, which we reach by Metro. We have been here on our first day in Tashkent but at that time it was very hot. The market is unbelievably large,

especially taking into account that in addition to the endless stands it has multiple two-story trading halls with roofs but not walls and also a department store. Everything is here: food, clothes, appliances, jewelry, and on and on. In the built structures we find one large hall with only rice and beans, another with breads, and another with sweets (we buy a chunk of halvah), several with fruits and vegetables. Sunday is apparently a market day because the place is crowded with people. It is nice to observe the locals with their shopping and their comings and goings. We find a small eating place where we have another excellent thick soup of noodles, broth, veggies and beef, together with bread and tea. Simple but a great treat if you are tired, thirsty and hungry.

The rest of the afternoon and evening we stay close to the hotel, including dinner, as we find out that none of the neighborhood restaurants serve wine or beer.

Tashkent to Voorschoten, Monday, October 15

Alarm clock at 2am. Hotel wake-up service fails us; they woke up the wrong person in room 208 instead of our 308. The taxi promised by the travel agency does not show up on time, so we take a taxi.

After long flight through Istanbul we arrive in Voorschoten in mid-afternoon to a beautiful fall weather. It is great to be home.