Sunday-Monday-Tuesday, June 16-18.

The conference at the Katowice School of Economics. Halina’s keynote speech at the conference brought us here.

Tuesday, June 18, Katowice.

An excursion to the Katowice coal mining museum. Unfortunately the guide talks a lot but shows very little; and the museum is modern but does not show the grittiness that Philip remembers from the old coal mines in Belgium: dust, fog, mountains of waste, and rain. In contrast this museum is clean, modern, and light. The trip includes a real mine tower which we access by an elevator, but there is no access to the mining shafts, which would make this trip a real winner. It is a curious phenomenon: tourists come here to see the authentic remnants of the gritty mining era but the hosts want to show them the post-industrial “clean” developments of the region: the art, architecture, cultural amenities. I have seen this phenomenon before in a different configuration. When asked where to shop locals usually direct us to the modern shopping malls with familiar chain stores while we are looking for local shops with local merchandise.

Philip leaves early for the hotel and Halina spends more time in the exhibit of the history of Silesia. This was a German region for many centuries, a jewel in their economic crown, with rich deposits of coal, minerals, and metal ores, and with rich agricultural soil. Poland made a claim to this area relatively recently, after WWI.

Wednesday, June 19: Krakow

Today we have several hours for visiting Krakow until the evening train to Warsaw. The bus trip from Katowice to Krakow takes about 1 hour. While exiting the bus station we encounter a man with a loudspeaker asking people to sign some kind of a petition. He talks about the worldwide Jewish conspiracy to soil up the good name of Poland as a collaborator in the Nazi crimes. What a welcome!

We walk over to the old city square, as beautiful as we remember it, though very touristy. We eagerly wait for the hourly hejnal, cut short by a mortal arrow during the 13th century Tatar invasion. We spend considerable time in the Mariacki Kosciul (St. Mary’s Church), the highlight of which is the ceiling painted blue with stars and the 14th century triptych by Wit Stwosz about life of Jesus. This is an amazing piece of art. It is carved in wood and painted. The human figures are incredibly realistic even by modern standards. Their poses, flowing robes, facial expressions, even veins on their work-worn hands tell their own stories. Apparently the models used by Wit Stwosz were chosen from among working people in Krakow, not the upper classes, precisely to allow him to capture the details of the individuals depicted in his art. The story goes that during the recent past a medical specialist visited the Church and when he noticed the swollen legs and some other body details of one of the carved figures he diagnosed him as having some kind of circulatory disease. The triptych was removed from this church during the German occupation to prevent the Germans from stealing it. It was send down the Wisla River to Sandomierz. Unfortunately the hiding place was betrayed by someone and occupiers took it to Germany, where it was stored in some wet basement, getting damaged. In the meantime, the high commanders ordered not to do any damage to Krakow and its art so that after the war the victorious Reich could enjoy the city for themselves, just like they planned for Prague and Paris. Currently the triptych is undergoing restorations, so only parts of it are visible. A computer monitor in the church shows the details of the process of renovations, which we find fascinating and spend quite a bit of time on it.

In the afternoon we take an Uber to the Benedictine Monastery situated on a mountaintop outside the city, known as Silver Mountain. This particular branch of the Benedictine Order lives according to the strict old monastic rules of silence, self-immolation, and prayer. They do not allow women in, except for one or two times of year. I am prepared to wait outside for Philip but as it happens we discover that June 19th is one of these days, owing to the feast of Corpus Christi on that day! The problem though is with Philip’s shorts, which are not allowed in. Fortunately, a nice man who frequently visits the monastery offers Philip a blanket from his car to wrap his legs in, and we both enter. There is really nothing much to see apart from the main chapel because the most interesting part – the village where the monks live – is off limits to visitors. What is more interesting for us is the conversation with the monk who leads us and the explanations offered by the blanket man. The monk has a kind of beatific smile on his face and emanates tranquility. But the order is clearly dying out; there is only a handful of monks living in this huge place. They own a lot of land. The blanket man tells me that he is partly Jewish (I think one quarter) and tells a long and complicated story of his grandparents’ survival during the Holocaust, hiding in plain sight in Krakow.

On the way back to the city, bitten all over by mosquitoes, we stop at Wawel castle. The castle goes back to the 12th or 13th century, the beginnings of the venerable Piast dynasty. It dominates the landscape, perched as it is on top of a steep hill, it is huge a truly impressive. There is no time to go inside, so we admire it from the outside. We walk down back into the old town which by now is a tourist zoo. A quick dinner in a relatively quiet place in a Park and we catch a train to Warsaw. We arrive at 10 PM and easily find our AirB&B, which was a pleasant old-fashioned apartment in the center near the street where I grew up.

Thursday, June 20, Warsaw

Everything in this apartment reminds me of the place where I grew up. The building is part of the Municipal Residential District (MDM), which was one of the first areas rebuilt in the almost leveled Warsaw after the war. The architectural blueprints and the materials are identical to my building on Nowowiejska Street. The high ceilings, the unpolished stone kitchen countertops, the hardwood parquet floors in a herringbone pattern, the granite stairs in the stairway: all are the same. This apartment used to belong to our host’s grandfather, so even the furniture is familiar: a Polish version of Danish contempo from the 60s and filmy white window curtains. I instantly relax.

The plan for today is to spend it with Ewa and Tadeusz. Philip has some digestive problems and stays home until afternoon, while Halina takes a bus to Ewa’s new apartment in Ursynow. Ewa is very talented in interior decoration and space design. The smallish new apartment is perfect in every way. I am full of admiration. No sooner do I arrive that Tadeusz disappears and four women with whom I went to elementary school (1957-1962) arrive for a small reunion. Two of them I instantly recognize and two require a second look and a comparison with old pictures. For the next two hours we talk, and talk, and talk.

I ask everyone to tell a short story of a vivid memory we have of those school days. Interestingly, Ania and I have the same story to tell! The episode had to do with a party in her house and her handsome much older brother. At some point I sat, or rather threw myself, on a couch in an exuberant moment of laughter, and inadvertently landed on a pile of records which the brother had borrowed from his then girlfriend. To our collective mortification every single one of these records broke. I never got over the trauma and guilt, and clearly neither did Ania. Ewa told of the time when she and I wrote with our blood on a piece of parchment “friends forever” and buried it in a container at the school yard. She tried to find it many years later, to no avail.

All of us pursued professional careers and did well in them: as book editors, national library curators, high level ministry officials, academics (me), …..Notably, these were all salaried jobs, not in business, which is partly explained by the communist system beginnings we had, and partly by the types of families that congregated in our school, which at the time was one of the very few schools in Warsaw without religious instruction (a short-lived experiment in a post-Stalin general political thaw). There were many Jewish children in my class, way out of proportion to the general population. The parents were in many instances sympathetic to the communist government or actively supportive of it, as mine were, though nobody wanted to talk about it, then and now.

I try to reflect on more general topic but do not succeed much because the women prefer to talk about details of their lives, marriages, jobs, children, financial status. But I do ask at some point about the views of their parents on the communist regime. The answers are rather vague, almost apologetic, for the sympathies that clearly existed. For me, my parents’ communist values are simply part of my personal history as well as the history of that region. I also often disclose it to my American friends as an act of defiance and personal distinction. But for these women, the topic is clearly a somewhat unresolved inner conflict, politically sensitive.

But we all agree that our school was highly intellectual and progressive, and that made a difference in our lives. Ania, one of us, is a devoted activist opposing the current government and its curtailments of democratic processes, its collusion with the Catholic Church and its violations of the Constitution.

We also talk about the boys in our class. I discover that some boys who pursued me were at the same time kissing other girls. They must have instinctively understood that I was too immature for kissing, even if they were attracted to me. It took these almost six decades to clarify various relationships and behind the scenes goings on. I also learned that the Jewish boy I very much liked, Sasha, was not allowed to play after school with non-Jewish girls.

After the reunion Tadeusz reappears and the three of us have lunch, then take a bus to Old Town. Philip joins us. After walking far too much on this extremely hot day we settle for dinner at Ewa’s favorite little restaurant in New Town, erected in the 17th century outside the walls and the mote of Old Town. We see a Catholic procession walking right by our outdoor dinner table.

The day offered me an opportunity to see Warsaw and to admire its loveliness. Since the 1990s it has become a very pretty modern city with history and culture. Women are dressed nicely and walk with their backs straight. And its public transit is fantastic. We can basically go from anywhere to anywhere quickly, comfortably, and, for us over 70, for free. This explains why bicycle sharing never took off in Warsaw. But we see many people using Lime Scooters, especially in the neighborhoods frequented by younger people. I stay away from trying one because if I hurt myself it would ruin our trip. But I will do so when we are back in the US. Philip however tried it several times and enjoyed it greatly. Krakovians turn their noses at

Warsaw as less cultural, more vulgar, more commercial. They are right to a degree but with these characteristics comes energy. And we can sense that energy in Warsaw.

Friday, June 21, Warsaw

Charlotte is our favorite café for breakfast. It is just around the corner on Plac Zbawiciela (Saviour Square, named after the imposing church which dominates it). After the first morning the waitress already knows us and remembers that we take our coffee black without sugar. Their bread is heavenly, I eat far too much of it, but cannot help myself. The area is now a hotbed of hipsters, full of young energetic people, busy, engaged. To me all the girls seem pretty and all the boys are handsome.

In the morning I meet Basia, a dear friend from high school, in front of the magnificent Lazienki Park for about an hour and half to catch up in Polish. It is such a satisfying conversation: each of us is truly interested in the other’s reports, and get deeply into them. Basia is one of these rare humans who are able to listen; she asks questions, she probes. She tries to understand and learn. Most people prefer to talk about themselves, especially women.

In the meantime, Philip tries out a Lime scooter, the same company that offers bike sharing services in Newton, our home town. For all the talk about global corporate takeover, some of it makes our lives much more convenient. All we need is to scan our US app for Lime to use the Warsaw scooters. The same is with Uber, and the same is with using public transit. Our American map app tells us what tram or bus to take and where to get on and off, which makes moving around any foreign city easy. Let’s face it: this technology is amazing.

Philip later joins Basia and me for lunch at the café at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in the Park, after which the two of us walk the familiar streets of Halina’s neighborhood, including “our” building and the windows on the (Polish) second floor. We explore the newly developed waterfront at Vistula River, full of bars, cafes, and featuring some new university buildings and a small man-made beach. We also visit a modern art museum at the river front (not especially interesting). The area is full of people, singles and families. We sip Marguerites at a hipsterish bar.

As the evening approaches we take another bus to the Rozbrat stop and walk through the magnificent but very buggy Lazienki Park up the hill to the Chopin statue, where we sit in the stillness of a warm summer evening, immersed in the aroma of flowers.

Saturday, June 22, trip to Tykocin.

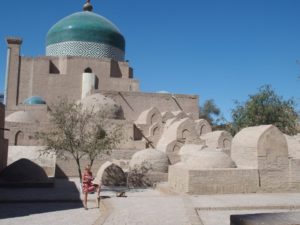

Tykocin is a small town, more like a village, about 100 miles northeast of Warsaw on River Bug. At some point in history it was an important commercial stop for grain trade on the river but by the 20th century it became a small poor village. Its present claim to fame is an old synagogue which miraculously survived the war. In 1939 Tykocin was taken over by the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union was invaded by the Nazis in June of 1941, around 2000 Jewish inhabitants for Tykocin, (half of its population) were executed in August of that year in the nearby forest. According to the Wikipedia about 150 people escaped but most were murdered by the local population. Some made it to the nearby Bialystok ghetto and eventually shared the fate the Jews there. As was the case all over the country, the Jewish properties were of course taken over by their neighbors. Since the war Tykocin has never recovered its commercial heart, and for that reason the houses from that era still stand. Halina wanted to see an authentic shtetl, so we went to Tykocin.

We take this trip with Wojtek and Danusia in their car. It is a very hot day. Over the years it has become a tradition that while in Warsaw Halina goes on an outing with Wojtek and Danusia. In the past we have together visited Lublin, Kazimierz Dolny, Sandomierz, Wroclaw, Plock, Mazury and Malbork.

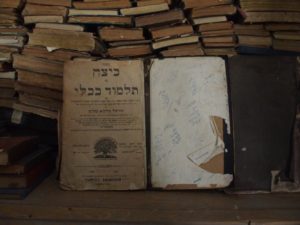

We arrive in Tykocin at the height of the day, scorching hot. There are many people visiting the synagogue, all Polish. The building has been restored but most of it is original, dating back to the mid-17th century. It is treated as an art museum and the place for learning about Jewish religion. The audio guide informs visitors about the main religious rituals — the minion, the use of bimah, the location of the Tora scrolls, the fate of the silver chandeliers — but rather superficially. For example, there is no explanation of why there is a women’s section.

And all of it is abstract. Not a single word about the Jewish people of Tykocin who worshiped here, who lived here for centuries, who settled here from somewhere and at some time, who built houses and schools and this synagogue, who were neighbors and business associates of the Christians. The wall plaque tersely states in one sentence that the Second World War has ended the Jewish culture and life in Poland. That is all. Philip gets very angry at that and conveys his feelings to a woman who seems like a supervisor of this place. I say nothing because there is nothing to say.

After the synagogue we walk around the western part of the village — the Jewish section — looking for very old wooden structures. We identify several of those by the specially decorated window frames and asbestos roofs. Everything here is very modest but these shtetel cottages speak of past poverty. We pass an empty grass field with a sign “Jewish Cemetery” and I am glad that at least it has been left undisturbed, with no buildings upon it. And glad that they have not turned this village into a Hollywood set as has been done in the Kazimierz section of Krakow.

After stopping for lunch in a village nearby – rich traditional Polish food – we take a small detour to visit my brother’s and Wojtek college friend in her summer house on Bug River. It is a beautiful large garden with an expansive view of the river and fields beyond from its high river bank. She gives us a very detailed tour of the house, opening every drawer, storage cabinet and the shed. It seems that she invited us to show us her property. This feeling is reinforced during the conversation over excellent wine and pastry, when she does not ask any questions about us or her friend my brother but shows us the photographs of her trips around the world. Nonetheless this is a very pleasant visit and we like her visiting girlfriend. I have low expectations of people when it comes to being curious about other people. People mostly want to talk about themselves.

We run out of time so we decide not to stop at Treblinka, which is only a few kilometers from here. Halina forgot her expensive sunglasses in the restaurant where we had lunch, so we need to return to the restaurant, an extra two hours driving. Based on my research, Treblinka was second only after Auschwitz in the number of people exterminated there, but its claim to fame was a successful prisoner uprising in 1943, after which the camp was liquidated. Only a monument marks the camp.

We arrive in Warsaw late, really tired.

Sunday, June 23, Warsaw.

This day was set aside for the Jewish History Museum, Polin. Philip does not connect with the first half of the museum, with a lot of texts and citations about Jewish life in Poland during the earlier centuries, starting around the end of the first millennium. There are no artifacts of any kind, only pictures and quotes from sacred and secular texts. For Halina, who is familiar with Polish history, this all makes much more sense. She could easily stay here much longer, getting into the weeds of the stories. Philip likes the coverage of the 19th and especially the 20th century, finds it more interesting and at times impressive. This is probably because he understands the historical context.

The highlight of the exhibit is the video of a televised speech given by the first secretary of the communist party Wladyslaw Gomolka in March of 1968. In it, he denounced the “Polish citizens of Jewish extraction” as the “5th column” and “Zionists” whose patriotic loyalties lied with Israel, not Poland, and who should therefore follow their preferences and leave Poland. He also said that such people cannot hold responsible government positions, which was a thinly veiled call to fire Jews occupying high positions in the government, industry and academia. I still remember that speech. Mama turned off the TV and said: this is the end of us in this country. And she was right: in short order, Tata was thrown out of his job in industry, Heniek was harassed and jailed for several days, one dawn our apartment was searched by men in trench coats, and we received a notice to vacate the apartment for some other place, away from the city center. By August 13th I was already on the train to Vienna, never to return (the official banishment lasted for 22 years). Today, 51 years later, I can still feel the fear we felt on that March day. Even Philip, who has heard this story more than once, is a bit shaken by Gomulka’s speech, trying to imagine how he would have felt in my place.

A museum guide stops next to us with a group of Japanese tourists, explaining in English what happened to the Jewish people in 1968. I remark to her that I am one of these people, which wakes up the listless tourists. She asks me an interesting question: how long did it take for me to want to visit Poland again. When I answer 23 years she says “I am not surprised, “ and nods as though saying: I would also hesitate before returning, after what you went through.

After the museum we slowly walk through a park (so many parks in Warsaw!) toward Old Town, which is a tourist zoo at this time of year. We meet there Wojtek and Danusia and find an elegant restaurant in the neighborhood of the Grand Opera House for a light dinner.

Monday, June 24: from Warsaw to Tallinn.

We say good-bye to our AirB&B and café Charlotte and take an Uber to the airport. The weather forecast is another heat wave in Warsaw, with 35 degrees expected by mid-week, so we are happy to escape to cool Tallinn in the north. At the Tallinn airport we discover another car sharing service, headquartered in this part of Europe, called Bolt (nothing to do with electric car Chevy Bolt in the US). Philip downloads its app. Our hotel Imperial is very comfortable and well-located.

After checking in we explore Old Town: climb the steep hill along Pikk Jalg, visit the Orthodox cathedral on the top, walk around the House of Parliament and Prime minister’s palace, and roam the narrow streets. The houses here are mostly Medieval and Renaissance, with some Baroque. We both have seen such charming old towns in other countries and cities, but Tallinn is among the most beautiful. What makes it special is that most streets have gentle curves in them, even small alleys. The result is that we can see the buildings present themselves both from the sides and from the front facades. And the curve at the end creates a sense of mystery. In addition, the ancient walls and fortifications are blended with residential houses, older and more recent, so the textures, colors and heights are always varied.

The Old Town is overrun by tourist groups. The Chinese speaking groups especially stand out. These tourist groups are unloaded in the morning from enormous cruise ships parked in the harbor and depart in early evening. It gets quiet and cozy here in the evening. And the evenings are very long. The sun sets at around 11 and rises around 4 AM but it never gets really dark here. These are the white nights near the Arctic Circle.

After a dinner at the supper touristy central Town Hall square we continue exploring the city. It is after nine and the sun is still flooding us with bright light. We visit a medieval basement which has been turned into an art studio of an entrepreneurial and somewhat shady Ukrainian character, and walk back toward the hotel along the old medieval city walls reinforced with several round towers, truly impressive and very well preserved.

Tuesday, June 25, Tallinn

The history of Estonia and their language is that of foreign dominance and suppression. Estonians are ethnically related to Finns, and so is their language. Tallinn was founded in the 13th century by Danes involved in the Hanseatic trade along the Baltic and North Seas, though there was a settlement on that site much earlier. A century later Danish king sold that land to German-speaking Teutonic Knights of the Cross, the leftovers from the crusades and headquartered in Malborg (Marienburg) in Poland. By then Teutonic Knights were masters of the area where Prussian tribes lived for centuries, and which by then were practically exterminated. They were also steadily invading traditionally northern Polish lands. The expansionist Teutonic Knights (Krzyzacy) were for several centuries the nemesis of Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians. Very quickly all the Estonians, whose economy was based on agriculture and fishing, were relegated to serfdom while all the manor houses and city dwellings belonged to the Germans. German was the language of trade, cultural and governing elites, and scholarship. And after only partially successful attempts by Teutonic order and others to bring Catholic Christianity to this region, by the 16th century Estonia became Lutheran.

Between the 16th and 18th centuries Estonia belonged to Sweden, and from the 18th century on to the Russian empire. After the WWI Estonia established its independence but that did not last. In 1940 it was invaded by the Soviet Union, in 1941 by Germany, and in 1945 became a Soviet republic. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union Estonia is independent. It is amazing how quickly Estonian language has been adopted by its population, considering that since the 13th century it has been preserved mostly by the peasants. At the same time we hear a lot of Russian on the streets and in restaurants. The Bolt drivers, and restaurant and hotel personnel seem to be predominantly Russian.

After a modest breakfast at the hotel we take a Bolt to the open air museum in a forest outside the city, partially to escape the tourist hordes, and partially because we want to see the countryside. It consists of many original farmhouses and farms from the past going back several centuries. In many of the sites women dressed in historical clothes are eager to offer explanations. They do not play roles but rather serve as tourist guides. They tell us about the history of Estonia and its domination by Germans, Russians, Poles, Danes, and Swedes, and about the emergence of Esotnian national identity during the European national movements and romantic era in the 19th century.

We spend several hours here, walking through the woods on this sunny and cool day. In a fisherman houses we watch a long documentary about Old believers within the Russian Orthodox Church, sort of the Hasidim among the Orthodox Jews, who rejected various reforms within the church during the reign of Peter the Great. Escaping persecution they settled on a lake shore in Estonia. Like the Hasidim, their dress, songs, food, culture, family relations, and so on are rooted in the early 18th century.

After the park a Bolt takes us to Telliskivi Creative City a once decrepit industrial zone now brought back to life by hipster cafes and restaurants. We have a lazy and very tasty lunch under an umbrella and walk through the fashionable “DePoo” market back to the Old Town. After a short visit to the Great Guild Hall which houses the Estonia History Museum we finally get some rest in the hotel. The museum collection is small and rather thin but it is just right for our limited ability to absorb the thousand year history of this place.

After dinner at another fine outdoor restaurant we walk toward the sea. Outside Old Town the land looks neglected except for some recently built modern residential housing. The water front is full of possibilities but for now it is a field of weeds and stones from some earlier structures, and without sidewalks. From what we have seen through the car windows, the modern section of Tallinn does not seem to have any coherent design or style. Buildings of all types, rather ugly, streets crossing in various directions. Not too much indication of a thriving economy. But that may soon change. We are told that Estonia has an exceptionally large number of high tech start-ups and that Skype was invented here.

I was always curious how long the days are at midsummer at the Polar Circle. Now I know. It never gets completely dark. At the dead of night I look out the window. The sky is dark but not completely. It has shade of dark blue that usually appears on the west side about half an hour after sunset. It is a mysterious half-darkness when everything seems different than during daytime.

Wednesday June 26. From Tallinn to Riga

The Eurobus that takes us to Riga is very comfortable (4.5 hours ride). The landscape is green, flat and unremarkable; woody in Estonia and agricultural in Latvia. The entire drive between the two capitals takes place on a single-lane road and without traffic congestion. Entering Riga we immediately notice a difference: it is a larger city, better organized and more coherent. Looking at its skyline we identify the same building as Moscow University and Warsaw Palace of Culture and Science: the modern pyramid built by Stalin. I wonder how many more copies exist in the former Soviet territories. PALACE OF CULTURE

We are of course heading for Old Town. Here is a question: if we love old towns so much, and we do, then what is it about modernity that prevents us from building cities using that model: narrow curving streets, ornate houses on a human scale, each different from all the others? This is especially true today as city planners and others advocate for walkable, bikeable car-free cities. Is it because city development is left mostly to the market which finds tall sharp-cornered unimaginative buildings more profitable?

Hotel Neiburgs where we are staying is a beautiful renovated Art Nouveau building and our apartment on the top floor is great. We drove ourselves too hard in Tallinn, falling into bed at night bedraggled, and this time we resolve to take it easy. So after a quick reconnaissance around the neighborhood we settle in an outdoor café for a long slow session of appetizers and a meal.

Thursday June 27, Riga

The history of Latvia bears some similarities to that of Estonia. Riga was founded in 1201 by Germans and soon became a very important trading center of the Hanseatic League. Between the 14th century, when it was finally Christianized, Latvia was conquered by, in turn: Livonian Brothers of the Cross, Teutonic Knights of the Cross, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, and finally during the reign of Peter the Great by Russia. Its modern history is also similar to Estonia: 19th century national identity movements, 1918 liberation, conquest by the Soviet empire in 1941, liberation in 1944.

We take a walking tour of the city: 2.5 hours, great guide Tom speaking perfect English and full of humor and warmth. Good group, very engaged. His business model: he offers a free tour, welcomes people who join half way through, and then explicitly and charmingly ask for tips at the end. People are giving him tips of 5-10 euros and we estimate that he collected about 150. Pretty good for a city where a monthly income is around 900 euros.

The architecture of Old Riga is different from Tallinn. It is a mixture of buildings from many periods, ranging from Medieval gothic to Baroque and occasional 19th century, with many more 17 and 18th century buildings than in Tallinn. Some buildings have been built by incorporating the ancient city walls as their back walls, sometimes serving to connect two or more adjacent buildings. This, and the variety of styles, creates and lively collage. As before, Old Town belongs to tourists. And as before, we hear a lot of Russian spoken on the streets though more people in the service industry speak English than in Tallinn. Russians represent about half of Riga’s population. During the sight-seeing trip we pass by several theaters, big and tiny, as well as concert halls.

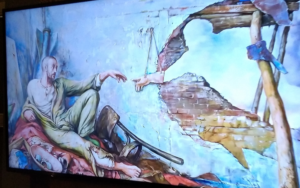

In the afternoon we go to a multimedia show entitled “From Monet to Kandinsky”. This show has been traveling internationally for some time. We really do not know what to expect. We enter a large rectangular room along with about 30 other people and recline on puffy chairs, floor, regular chairs, wall seats, some people lie down on the floor. The show begins with Monet’s ballet dancer moving to the sound of Chopin. On five walls of the room we watch paintings of famous 19th and 20th century artists, taken apart and put back together in an amazing collage, moving, running, sometimes static, sometimes extending from one to another, each painter accompanied by a different music track. It is imaginative and fabulous. The paintings we know so well reveal themselves in a new light, and so do the painters. Halina is struck by the sad faces of Modigliani, the passion and tenderness of Klimt, including her favorite unfinished Adam and Eve, the joy and playfulness of Mondrian. When the show ends after an hour we stay and watch it through the second time. Philip studies the techniques. Some painters are conspicuously absent, such as Matisse, Klee, and Miro.

Riga is famous for its Art Nouveau buildings. With about one third of its buildings in that style, Riga has the highest concentration of Nouveau buildings in the world. To see them we leave Old Town and head toward the famous Alberto Street and its environs. This gives us an opportunity to see other parts of the city. As we thought yesterday, this is a purposefully designed city. We walk through a park and along streets about 5-6 story high, clearly planned with a big picture in mind, and well cared for (at last in this part of town). We discover a fantastic collection of Art Nouveau buildings, many of them designed by Mikhail Eisenstein, father of famous movie director Sergei Eisenstein.

Art Nouveau buildings are characterized by very rich, in some cases fantastically excessive, decorations. They were all built during a period of rapid economic growth between 1904 and 1914. In that sense, they remind me of Budapest. The creation of the faculty of architecture in Riga in 1869 was instrumental in providing a local cadre of architects. The style is most commonly represented in multi-story apartment buildings. The decorations draw on images of animals and plants, folk art, Greek mythology, classicism, or pure fantasy.

On Albert Street we run into two women from our morning tour and we exchange tips about what else to see and do in Riga. Several tourists are taking photos of the buildings. This is a great and unexpected discovery.

Friday June 28. From Riga to Vilnius.

Before jumping on the final bus ride to Vilnius we walk the maize of Riga streets to figure out the geography of the Old Town. Seeing a place with a guide, without a map and the necessary searches for directions from sight to sight, makes the place kind of unreal. We visit the Guilds building known as “Blackheads”, occupied by German fraternity of unmarried seafaring traders going back to the 1300s. The building is beautiful from the outside and very interesting inside: it has been completely rebuilt after WW II following old blueprints. It is richly ornamented outside. Inside we study a very interesting central heating system in the basement and the opulent rooms upstairs.

Another four-hour drive and we settle in a very comfortable Hotel Vilnia. Its location is perfect: on the edge of Old Town and at the foot of the steep castle-fort hill, and across the street from a large park. A stroll through the park is a perfect thing to do after a long bus ride. The park resembles Lazienki in Warsaw. Its walking paths and benches are formal, yet there is a certain amount of wildness in the trees and shrubs. Across the river is a steep hill with a monument of three crosses on top. Further on top is an old castle.

Tonight over dinner we listen to a three men band (cello, violin and accordion) playing and singing folk tunes. Later in the evening we sip wine in another café and invent a story while watching a well-dressed and made up young Lithuanian woman with a much older American man. Seems like an escort service.

Vilnius (a Lithuanian name; Vilna in Yiddish; Vilno in Polish) is altogether different from Tallinn and Riga. It is a grand city. Old Town is not as radically different from the rest of the city because its buildings are much younger: mostly 18th and 19th century. The grand-ducal palace is much older, going back to the 13th century when the first dynasty was established (from which Jagiello’s dynasty that ruled Poland between the 14th and 17th centuries derived) but the structures surrounding it are mostly Baroque. The park across the street from our turn-of-the-century hotel is similar to Warsaw’s Lazienki: wild and formal at the same time, lovely. The wide avenues circle the city, the main walking streets are expansive. There are plenty of small alleys with 2-3 story buildings, always curving gently, often hilly. And the courtyards are everywhere, just like in Budapest.

Essentially, in Vilnius all our waiters speak very good English; they look and act like modern cosmopolitan students. The boys are very handsome and girls are pretty. We hear very little Russian on the streets and in the popular cafes at least half of the patrons are Lithuanians, not foreign tourists. A big contrast with Tallinn, where Old Town is deluged with tourists and many local people do not speak English.

Tonight we take in the geography of Old Town. Our wanderings take us to the old Jewish section and inside the perimeter of the former Ghetto from the German occupation days. We encounter a small synagogue, renovated and practically rebuilt after the war. This is a functioning synagogue for the remnants of the Jewish community in Vilno. It is closed. As we wander through the somewhat shabby neighborhood we encounter occasional store fronts with old signs in Hebrew letter. I always like courtyards so we enter several. In one we come across a very tall, maybe12 feet high, ghetto wall. It just stands there, separating this one from the other abutting courtyards; silent, unrecognized, unmarked, sad.

Saturday June 29, Vilnius.

We take a light breakfast in a chick café across the street. The background music of the early Beatles plays in the background. I tell the young clean-cut boy-man at the counter that I used to listen to this music in high school and that it was so long ago that he could be my grandson. To this he replies, looking serious and earnest, that this is classical music, so of course!

The plan for today was to visit the Grand dukes’ palace and then the castle on top of the hill. I have great interest in the grand dukes of Lithuania because Poland and Lithuania were joined – first through marriage, then as a formal commonwealth — between 14th and the end of 18th century. Learning Polish history in school I am familiar with various grand dukes, several of whom were also kings of Poland.

The first round through the museum takes us to the structure of the castle and into the history of dynasties of Lithuanian grand dukes and Polish kings. The Lithuanians, like Latvians and Estonians, were the last European people to be christened (about mid-14th century, but in reality not until the 15th century did Christianity take deep roots). The modest grand duchy entered into a union with Poland in 1380 through a marriage of the only daughter of Polish king Kazimierz the Great to Lithuanian Grand Duke Jagiello. So ended the first Polish royal dynasty, the Piasts and started the second one the Jagiellonians. Over the next two centuries Lithuania came to dominate the Polish kingdom, though the pope never gave its monarch the title of a king, presumably not trusting their commitment to catholic Christianity. The Lithuanian part expanded enormously throughout the next two centuries until it reached Black Sea and it became the largest country in Europe. At its greatest expansion Polish territory was only half the size of the Lithuanian territory.

The Commonwealth reached its peak after both countries signed the formal Union of Lublin in the middle of the 16th century. Although Poland had kings, it was in practice a republic because the kings were elected by a legislative assembly –Sejm — comprising all free people. It was a multilingual, multiethnic and multireligious country, tolerant of diversity, and rich. Jews thrived here and Vilno came to be called Jerusalem of the East. It hosted great schools of Jewish learning, philosophy, and culture. But this giant had clay legs. As a republic it lacked a constitution or a properly designed executive branch. As a monarchy, its kings were very weak, depending on great aristocratic families to support the military. In the Sejm a single oppositional vote (so called liberum veto) could invalidate the entire proposed legislation and months or years of deliberations and compromises. The economy depended on exports of grain and local sales of distilled alcohol, all on the backs of serfs and their alcoholism. Commerce and manufacturing was slow to emerge so the burgher middle class was small and disrespected. The nobility had more loyalty to their own interests than to the country as a whole, and the royal elections were manipulated by foreign countries through greedy and corrupts nobility.

The decline started in the mid-16th century with the Chmielnicky uprising of peasants in Ukraine. This was quickly followed the Swedish invasion. Russia began to devour pieces of Lithuania and Poland. Finally in 1772 the partitions of Polish and Lithuanian Commonwealth began, without a single shot being fired. The Commonwealth was sold out. By 1795 the third partition eliminated Poland and Lithuania from the map of Europe. All the unrests and uprisings took a huge toll on the Jews, who were murdered by the thousands. In 1919 Poland and Lithuania both re-emerged, but the city of Vilnius was in 1920 incorporated by Poland. After WW2 and the Soviets it finally regained independence in 1991, but it has shrunk beyond recognition.

Apparently, the national pride created massive funds for this fascinating and quite modern museum. After several hours on our feet we managed to quickly do round two in the castle, focusing on the interior rooms, and skipping two other rounds. We emerge from the palace museum well into the afternoon, more than ready for a break.

I am fascinated by the difference between the Polish history I learned in school and the Lithuanian perspective here. In the Polish rendition Lithuania was basically Polish, while in the Lithuanian rendition, without Lithuania Poland would have never succeeded in defeating the Teutonic Knights and other invaders during the first two centuries of the existence of the union. For Halina this entire exhibit is fascinating; Philip is also fascinated by Halina’s fascination.

This exhibit impresses upon us the impermanence of everything in history, be it ideas, power balance, or borders. First Lithuania dominated the Union for two centuries, then Poland dominated the Union for two centuries, then the entire enterprise disappeared for more than a century while the Russian, Habsburg and Prussian empires grew. After the First World War the three empires collapsed and the little Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland started to figure out how to become modern democracies, with little success, as dictators took over one after another. And so it goes. A few years ago the West thought that they were permanent democracies but now we see that this cannot be taken for granted. The East is not democratic and the pressure is moving westward.

Being in Vilnius allows us to compare the four cities: Tallinn, Riga, Vilnius and Warsaw. If we were to move through them in that order we would find the following: the knowledge of English among the people we encounter in restaurants, shops and taxis increases; the presence of Russian language on the streets decreases; the cities get larger and their Old Town buildings get more recent; the presence of foreign tourists declines. And the history of foreign dominations seems to get less complicated: Estonians were relegated to peasantry and serfdom while the manor houses were all German, and the areas changed the hands between Sweden, Prussia and Russia; Latvia was a contested territory, dominated by Teutonic order of the cross between the 13th and 15th centuries, then by Prussia, and much later by Russia. Poland and Lithuania were mostly independent and rather dominant (though with forever adjusted boarders) until the partitions at the end of the 18th century. All four countries became independent in 1918 but were not very good in building democratic systems, leaning toward dictatorships and became either absorbed or controlled by the Soviet Union after WWII.

It is amazing how quickly these countries reverted to their original languages since 1991. Consider that Estonian and Latvian were mostly spoken by peasants, while the literary and power elites used German and other languages (Swedish, Russian). In Lithuania the process of Polonization was so strong that by the 16th century the great dukes of Lithuania did not speak Lithuanian. And the process of Russification was no less strong. And now, less than 30 years later, everybody in the three countries (except probably some ethnically Russian families) speak their own national languages.

We find a nice small Lithuanian restaurant nearby and had our lunch/ dinner, blinis Lithuanian style. We linger and make plans how to spend the rest of the day. We find on the map an old Jewish cemetery; and call a Bolt to bring us there in a few minutes of reckless driving.

To our dismay the cemetery does not exist anymore. During the soviet era all the gravestones were removed and used as building materials: stairs, buildings, walls. A modest monument at the entrance is made of gravestones and informs visitors that since 1830 seventy thousand people were buried here. But apart from us there are no visitors here. We climb the steep hill and cross to a grassy wooded area with hardly any traces of stones left. Shocking. Coming down we discover a large modern building in brutalist style of the 70s built on the cemetery field. In a macabre joke of sorts the building is a Christian funeral home. Behind it there is a very large of gravestones, some with Hebrew letters still visible pile.

I comment to the Bolt driver on the way back how disrespectful it is to build on top of Jewish graves (they must have also dug up human remains in the process). The driver blames it all on the Soviets. The usual story: the Nazis responsible for the killings and the soviets responsible for erasing the remaining traces of Jews. Everybody else claims innocence. Not a sign of national self-reflection. It is so profoundly sad.

Later, searching the web, we learn that the destruction of the cemetery was part of a deliberate Soviet policy to erase traces of the Jewish culture in Vilno. Another large cemetery was also destroyed at that time, around 1960. As part of that process, the partially war-damaged Great Synagogue of Vilno, with a capacity for 5000 people, was also torn down in 1957 and a kindergarten was built on that site.

Back in the city center stumble into a Russian-Orthodox service and stay for a long time. In the haze of the incense, candlelight, and beautiful pre-Gregorian choral music our nerves calm down.

Saturday, June 30. Vilno.

We start the day by walking over to what we think is the Jewish historical museum; it turns out to be a cultural center with a very interesting art exhibition by Samual Bak, a child survivor of Vilno’s ghetto whose paintings depict the horrors of the holocaust (he lives in Weston, Massachusetts). After another steep walk we reach what we thought was the Jewish historical museum. It is closed and it looks neglected and deserted. So much for a state-run Jewish museum in Lithuania. It appears that the so-called branches of the state museum are run separately with philanthropic funds while the official state museum is dying. This time it cannot be blamed on the Soviets.

By now it is pretty hot; the heat wave that swept Europe and that we escaped so far had now reached us. We take a Bolt to Panar Woods, a site of mass executions, about 10 miles outside of the city. This is a very pleasant forest with railroad tracks running through it. On this particular Sunday the sun is playing with the lovely green of the trees and a pleasant breeze makes it a perfect weather for an outing. There are almost no visitors in these woods. The parking place is empty except for one bus which soon disappears, and one car belonging to a nice young Polish couple with whom we have a brief conversation.

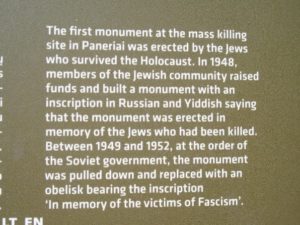

Here are the facts. About 100,000 people were murdered here by mass shootings of people standing on the edge of large pits, which were to be their mass graves. The majority of the killings took place in 1941, soon after the German invasions of the Soviet Union. 70% of those killed were Jews from Vilno and other parts of Lithuania. Of the approximately 80,000 of Jews living in Vilno at the time of the German invasion in June of 1941 (half of the city’s population) about 50,000 were murdered during the first 4-5 months. These murders were performed by shooting. There used to be more than a dozen pits, about 5-6 meters deep, each capable of holding many thousands of bodies. I did not count how many are currently marked but it is about 8 or so.

So this is how the Nazis, using the well-organized help from many volunteers among the local population, learned their first lessons in genocide. And this is where they discovered that a more efficient industrialized method of murdering and body disposal was needed. Sometime in 1943, when Hitler’s victory became an obvious mirage, the Germans decided to dig up all the bodies, burn them, and pulverize any leftover bones, all to erase the evidence of their crimes. This work continued until the spring of 1944. One of the pits we visited was a ‘home’ for 80 prisoners, including 4 women who prepared meals. The several meters tall walls of the pit are reinforced with bricks. There was no way to escape.

The job of the prisoners was to uncover the mass graves, pull out the decomposing bodies using special poles with hooks at the end, and deploying some kind of a simple machine with wheels and belts to help (today displayed in the pit), stack them up like wood and burn. They were called “brenners” or burners. These people knew that when the job gets finished they will be killed. So they decided to try to escape. For months they were digging an underground 30 meters-long tunnel, starting at the back wall of their shack, using literally soup spoons for tools. On April 15th, 1944, between twenty and thirty individuals made it to the opening of the tunnel, but when a twig broke under someone’s foot the Germans realized what was happening. They started shooting randomly into the darkness, killing some escapees. Thirteen people survived and were hiding for the next three months, until July 13th when Red Army liberated that area. They were able to tell the story. I would like to think that the local population helped them during those months.

In 1948 the surviving members of the Vilno Jewish community erected a monument to commemorate the martyrdom of the Jewish people in Panar. The government soon removed the monument and replaced it three years later with an obelisk to the memory of “victims of fascism.” Many years later, in 1992, when Lithuania had already declared independence from soviet occupation, another monument was placed in these woods, commemorating “Lithuanian victims.” What can we say: the Soviets as well as the Lithuanians could not bring themselves to acknowledge what happened to the Jewish community in Vilno and who took part in that tragedy.

On the other hand, I cannot understand for the life of me why the Jews of Vilno were so passive. For a year and half they listened to the reports about the fate of Polish Jews, the starving ghettos, the executions, the camps. Treblinka and Sobibor camps were not far from the Lithuania. And they did nothing. They could have at least tried to run east, away from the proximity of the German-occupied Poland. Mama and Tata did, to Ukraine and eventually Uzbekistan. Such an unbelievable denial of reality. I do not get it.

We need to change the atmosphere after the Panar trip. A Bolt car takes us to the modern art museum. The museum is rather disappointing, with only a few interesting pieces. After some rest in the hotel we take a final walk in “our” park, with strolling mothers and kids, young couples, and friends, enjoying the cooling evening, the beautiful low sunlight, the fountain that explodes every now and then to the sounds of music. It is a truly lovely summer evening: warm, breezy, gentle. The horror of the past leaves us bit by bit. We stop at the little vegan RoseHip café, order two glasses of wine and a bowl of borscht for Halina and walk one last time through the park, around the castle and tower.

Monday, July 1. Back in Voorschoten.

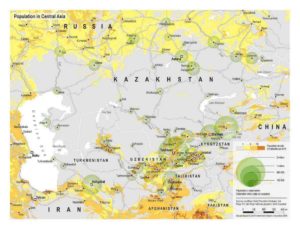

Uzbekistan and its neighboring “-stans” is that spot on the map — between eastern-most Europe, Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and Afghanistan – that, although once a big player in the history of Europe and Asia, for most of us is a blank space. So we take this trip in order to put some color and pattern into that space. We also have personal reasons to go there. For Philip, this is a return trip, after 23 years. For Halina, Uzbekistan is the place where her Jewish parents spent about 2-3 years during WWII, escaping the Holocaust.

Uzbekistan and its neighboring “-stans” is that spot on the map — between eastern-most Europe, Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and Afghanistan – that, although once a big player in the history of Europe and Asia, for most of us is a blank space. So we take this trip in order to put some color and pattern into that space. We also have personal reasons to go there. For Philip, this is a return trip, after 23 years. For Halina, Uzbekistan is the place where her Jewish parents spent about 2-3 years during WWII, escaping the Holocaust.