I recently attended a workshop convened by the Urban Sustainability Directors Network, USDN, on the topic of sustainable consumption. One of the issues that repeatedly came up was how to address income inequality while also promoting sustainable consumption. To pursue either of these two big questions is a big undertaking already, but the two together are mind boggling. So I took some time to educate myself on the relationship between household income and its GHG footprint (the latter standing for energy and material consumption).

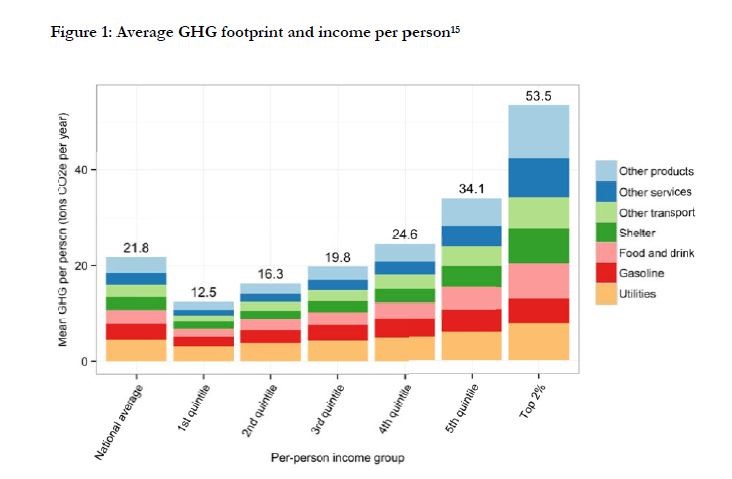

My key finding is that household income is a strong predictor of that household’s carbon footprint. This correlation is consistently and unambiguously reported in several recent studies in the US and Europe. As shown in the figure from the 2014 report by Center for Global Development among the US households the correlation is linear for the bottom 80% of income categories (up to approximately $120,000 for a family of four) and accelerates above it. The greatest acceleration is among the top 2% of income. Stated differently: the more we earn the greater our GHG footprint is, with households earning more than about $120,000 engaging in more carbon intensive lifestyle choices and amenities. One caveat is that it seems to me that the GHG footprint estimates for households in the top 5% income bracket are rather uncertain in all the studies I examined, but for the households in the 95% category (up to $200,000) the data seem to be strong.

With this knowledge, I tried the following thought experiment. Suppose we were to decrease income inequality by reducing the number of households with the extremes of income (at the top and the bottom) and increase the number of households in the remaining categories, say between 20 and 80% income brackets. How would it change the total consumption-based GHG emissions? The answer is: they would remain more or less the same or because the top earners seem to be more GHG intense per dollar spent than the rest of us, perhaps a little lower. In another thought experiment consider what would happen to the total national GHG footprint if we reduced the proportion of households in the lowest income bracket by moving them into the middle-income category, without touching the households in the top category. The answer is that the total emissions would increase.

This is a disturbing thought in light of the questions posed by the Urban Sustainability Directors: raising the income of those who most need it will result in greater total greenhouse gas emissions unless we simultaneously reduce the income at the top. The latter is not only a political problem but also is largely outside the jurisdiction of municipalities. And come to think of it, increasing the income of the bottom earners is also for the most part outside the options available to municipalities. So what can municipalities do?

One idea that comes to mind is that instead of thinking of income, which households seem to be always converting into carbon emissions, the municipalities can think of providing quality of life (and keeping an eye on GHG emissions while doing so). The case in point would be to provide affordable high-quality middle-class housing in locations conducive to good life that is also extremely energy efficient. Extremely energy efficient construction, including the so-called “passive house” construction, is a technical challenge that has been already solved, but most developers and municipalities do not practice it. I will not go into this matter in this posting. Rather, I want to focus on affordable middle-class housing and good life. To pursue it, municipalities will need to think outside the box of the dominant model of a private developer and token subsidised units for the poor. In my next post, I will describe an amazing housing project in New York City, known as Penn South, that delivers high quality of life, affordable housing and a thriving community life on a modest GHG footprint in the centre of one of the most expensive cities in the world.