Wednesday January 11

We wake up in Newton with the TV message of a massive computer failure that grounded most airplanes in the US. We can sit out our delay at home. In the end, it is only a 1.5 hour delay. A friendly Lyft driver in New Orleans.

The International House hotel is a nice, rather old-fashioned place. The neighborhood is oldish, with many beautiful art deco and art nouveau buildings interspaced with smaller, random structures, most showing signs of some neglect. Two blocks away is a major thoroughfare, Canal Street, which seems like a border of the French Quarter and the beginning of its centerpiece, Bourbon Street. Philip does a quick reconnaissance and reports his pleasant surprise by the atmosphere: a nice mix of not-too-many tourists and locals making music in the streets; but also several homeless people lying around. I discover a nice courtyard annex café, very reminiscent of Budapest, where we later have dinner.

The food is mediocre but the drinks (sazerac and a cocktail of frozen peach with bourbon) are good, and the live music is great: a trumpetist annex singer, an older guy, and behind him an even older but identical looking guy, half hidden, playing the drums, and then a great young pianist. Halina asks them to play “gloomy Sunday” but they never heard of it. We go back to the hotel dead tired.

Thursday January 12.

For breakfast we try a place in Chartres street, not far from Canal street and the hotel. Halina’s eggs are greenish (from avocado butter) and look like vomit. Philip’s burrito is excellent.

The weather is uncommonly warm, in the 70s. We decide on a guided walking tour through the French Quarter that starts at 1pm, which gives us a few hours of leisurely walking, admiring the wrought iron balconies and further architecture of Chartres street, the music, life and recorded, everywhere, and the mix of black locals and (mostly white and overweight) tourists. We find the Cabildo building at Jackson square, the old government center that is now a fabulous museum. This is where the purchase of Louisiana was celebrated in 1812.

The history of the purchase is interesting. The French Canadians came to this area from the Gulf, having heard from the native Americans up north about the great river that starts in what is now Minnesota and ends down south in the Gulf. Once they found it, they claimed the entire territory of the Mississippi watershed as theirs, calling it Louisiana after the French monarch Louis XIV. The territory is huge, essentially the American Midwest. But the New Orleans area turned out to be a big problem: swamps, heat, mosquitos, yellow fever and malaria, and no particular economic value. So, after maybe eight decades or so, the King of France gave the Louisiana territory to his nephew, a Spanish royal family member who was also the king of Mexico. The Spanish did not have a lot of luck with this territory. Two major fires burned down most of the city, and the economy was weak. So, after half a century, they gave it back to France. At this point Napoleon was the ruler of France and, needing a lot of money to finance his wars, sold it the same year to the United States under President Jefferson, for 13 million dollars.

We roam the three stories with displays of the battle of the 1815 battle of New Orleans and Mardi Gras costumes. One artifact is interesting: a water pipe for the local waterworks, made of a trunk of a tree with an inner hole bored into it. On the third floor there is an exhibit of Creole life by a local contemporary artist (artistically not so great but a nice display of creole figures and their dresses and lifestyles). We need a break and find it in the grand café Du Monde near the river, where the only thing served are beignets and coffee. Beignets are fried dough, extremely fresh, crispy on the outside and fluffy inside, and covered with a thick layer of powdered sugar.

Our guided tour is a disappointment. The very nice guide talks and talks, she has many interesting stories to tell about the history of New Orleans, the architecture of the houses, but she hardly moves; we would stay at one place for 15 or more minutes while she is telling some complicated story, which is tiring. But we also learn a lot about New Orleans’ history. The French made a mistake by selling Louisiana to the U.S. Shortly after the sale, a method was invented for granulating sugar from sugar cane, which made sugar a huge export commodity to Europe. It was white gold. Then, the cotton gin was invented, which made processing of cotton into high quality yarns easy and created a boundless demand from the cotton mills in the north. New Orleans and the vicinity became very prosperous.

The tour has become long and tedious, so after 1.5 hours, when the group turned left around the corner we inconspicuously turn right and continue exploring the French quarter on our own. We recognize the houses with courtyards and small adjacent slave quarters the guide talked about, and of course the ubiquitous balconies.

We end up at the far end of Royal Street. It is not far from the tourist area around Bourbon Street and Jackson Square, but it is very quiet and lovely, with a completely different atmosphere. The architecture is very attractive, a variety of house types, and all these courtyards. We take some side streets, find a nice park to rest where dogs and kids play, have sandwiches in a little diner. Back at Jackson Square, Halina has a foot massage, while Philip rests nearby. The place is run by men from Far East Asia, the front door is wide open, I close my eyes and listen to the man outside, an electrical contractor describing how the electric system in his building is totally overrun by roaches and eaten through.

We walk back to the hotel through a riverfront park. A man is playing on a keyboard. The best-looking restaurants are packed, need reservations. We settle in a large family restaurant where food is much better than the previous evening but still not top quality. Heading home, we run into a street performance of two tubas, trumpets, trombones, and drums, with the most uplifting music; loud, but completely appropriate. A band like the ones we have seen in movies at New Orleans funeral processions.

Friday January 13.

Windy cold day, morning in upper 40s. We find a new breakfast place, Streetcar Café, conveniently near the streetcar stop. The breakfast and the ambiance are perfect. Our first destination is the museum of the Southern Jewish Experience. We step on the century-old streetcar with a large sign “only exact change” but of course we have no change and no idea where to buy tickets. The driver is irritated but sells us two senior day passes for the improbable total price of $2.62. We cannot figure out how he came up with that odd number, and he is in no mood to explain. The change comes in the form of electronic pass, supposedly to be used again. These trams have an uncanny resemblance to an ancient underground tram in Budapest: wooden benches and leather straps for the standing room passengers. They move very slowly but frequently. I watch a scene repeating itself with new groups of tourists: no exact change which means that the driver has to take their money and give them change in the form electronic pass. The tourists are happy, energized by the prospect of the day’s explorations and the driver gets increasingly impatient. A woman sitting across from me looks Jewish. And sure enough, a few minutes later we ran into her in the Jewish museum. This is my (Halina’s) Jewishness: recognizing other tribe members.

The museum is small, very new, and fabulous. Our visit starts with a ten-minute movie. The exhibits tell the story of Jewish immigration, lives, careers, business enterprises, persecutions, and integration into the social and business networks. It is open about the Jewish community joining the slave-based economy but does not go into any depth about it. We learn some new things: that the first Jewish settlers in New York in the 16th century were Sephardic Jews from Brazil when Portugal, following the Spain’s lead, forced the Jewish population to either convert or emigrate. Over time, they were greatly outnumbered by Ashkenazi Jews coming from Germany and, later, Eastern Europe.

We meet a local Jewish man who volunteers in the museum to answer visitors’ question. He and I get into a conversation about Jewish youth camps. We discover that their camps were very similar to the camps I attended in Poland: the effort to connect the assimilating youths with their heritage and to foster Jewish marriages. The curator of the museum is a musician specializing in Yiddish music. He regularly participates in the annual Jewish festivals in Krakow and Warsaw and knows people of my generation who did not emigrate in 1968. I point out to him that these festivals are fake, museal pieces and the entire current Jewish culture in Poland is a museal piece. He tells me that the people he knows in Poland are as adamant about Poland being their country as I am about the emigration as the right way to relate to Poland.

We are looking for a café. We find one nearby, very trendy and completely full, with people waiting half an hour outside to get a seat. We move a couple of blocks further and find a lovely modern café that is almost empty. That other café must be known on social media. People do not bother to explore on their own, but rather go where the fashion tells them to go.

It is now sunny and crispy, a perfect day for exploring the city. The next streetcar takes us to the Garden District where we visit the House of Broel, an incredible historic mansion with the most amazing collection of dollhouses. The entire upper floor is filled with them. There are different themes, time of the year, countries, historical periods. We get a private tour of the mansion and its content from an eccentric lady who runs the place. Halina loves these dollhouses and even Philip, who shows up just to please her, finds them enchanting. The House of Broel has an interesting modern history. Its owner Mrs. Broel, now in her eighties, started in her youth a business of custom-made gowns, mostly wedding dresses, for rich ladies. She bought this house in a very neglected state in order to be near her clientele in the Garden District and named her business as House of Broel. The name was modeled after French couture companies, such as the House of Dior or the House of Chanel. The entire third floor of the house is filled with gowns, some of them really beautiful and sophisticated in design.

When, in the 70s, American department stores started selling mass produced wedding gowns off the rack, this smart businesswoman decided to go into a full-fledged wedding business, using her mansion to its fullest potential. This is its primary business now. The clever lady went even further: in order to vertically integrate her business she became an ordained minister so that she could personally perform the wedding ceremonies. And she herself changed husbands a few times to boot. Now she lives in a lovely cottage in the back of the mansion’s garden. And our guide is a wedding manager. I wish I could meet this incredible Mrs. Broel. She reminds me of Helena Rubinstein and Este Lauder, also self-made business women in the fashion world, with very modest beginnings (differing only from Mrs. Broel by being first-generation Jewish immigrants, though who knows, maybe Mrs. Broel is one as well). While we are touring her house, she is getting ready for being a queen of some ball tonight in connection with Mardi Gras.

Completely saturated with the stuff and the stories, we get out to fresh air and something to eat. The rest of the afternoon, we explore St. Charles street in the Garden District, famous for its grand mansions. We take the tram to the end and walk back. At some point we find ourselves in front of a church-like residence with a huge, slate roof, almost like a Swiss Chalet. While we stand in front of it admiring the architecture, a gray haired woman of about my age emerges with a dog and we start a conversation. This was indeed once a church and the living room has 45 foot ceiling. The conversation goes further and we find out that she is German and her husband is a New Yorker, and they bought this house twenty years ago when it was already a private residence. She tells us about adapting to the Southern city and other details of their lives. She tells us that the house next door, which is a complete ruin, was sold for $2.5m to Beyoncé. An interesting story of it. The house was listed for 1 million and for a year there were no buyers. So the owners raised the price to 2.5 million in order to attract a different pool of buyers, and indeed it sold very quickly. It is an amusing lesson of understanding your market.

We are too tired to walk again through the French Quarter so we have dinner in a place across the street and cash in our free welcome drink in the bar of our hotel. We drink something called French 75, very light, champagne-based cocktail.

Saturday, January 14

Another cold day under a brilliant blue sky. The streetcar (Canal Line) takes us to Enterprise car rental, where we are in and out in about 20 minutes. I notice that the price of gasoline is $2.91, indecently low in these days of climate change. In less than an hour we are at the Whitney plantation. The landscape along the way is unremarkable. We drive in turn by desolate tracts of land not used for anything, swamps and forest. Here or there, we pass trailer parks that look unloved. Although the homes are tightly arranged, there is no attempt to turn it into an organized community. There are no trees or shrubs, no central open space for community gatherings, no beauty.

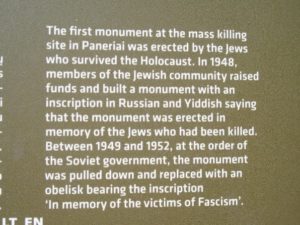

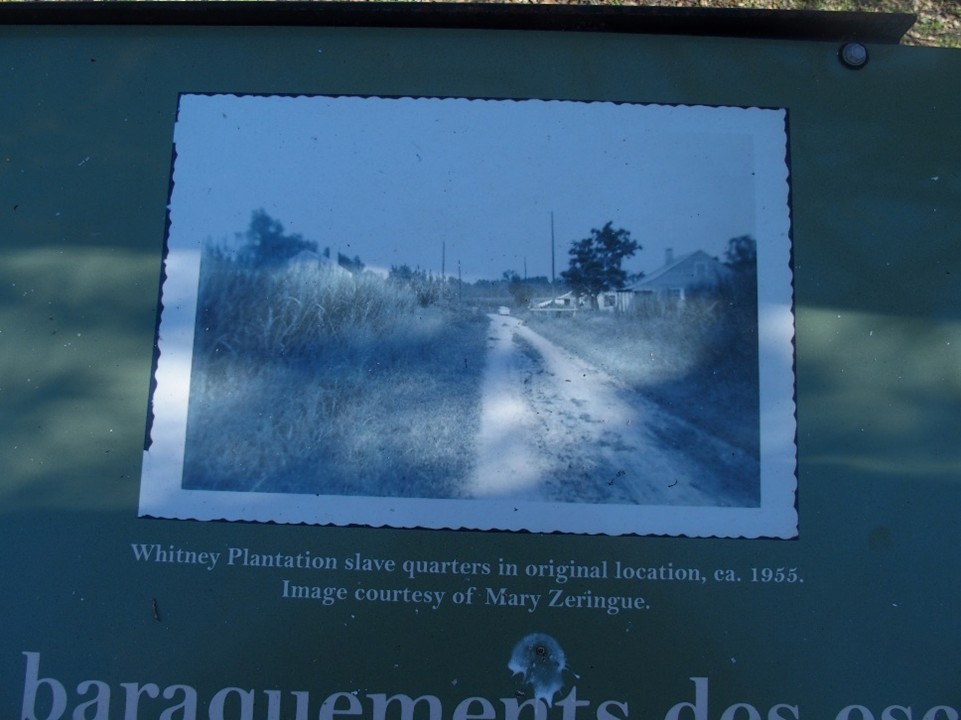

The Whitney plantation was a functioning business until it closed in 1975. Because of that, it has been preserved quite unchanged since the 350 enslaved people labored here. It employed many descendants of the slaves who were freed in 1865. Thanks to a monumental effort of some academic, a lot is known about the names, origins and fate of these people. We listen to recorded interviews with some of them, conducted in the 1920s.

We take a self-guided tour with about a dozen stops. The plantation has many sculptures scattered around, all deeply emotional and reminding us of the horror of slavery. The slow walk through the plantation, the accompanying stories as well as my memory of the movie 12 Years a Slave combine to bring slavery alive. Women were giving their first births as teenagers, producing a large number of children, many fathered by the white masters. The recording for visitors is silent on the paternity of these children. How many had the masters for fathers? And in what proportion of cases were these mulatto children classified as slaves by their own fathers? Were they sold as soon as possible to avoid the uncomfortable situation? At age 14, the enslaved children were considered to be ready for full time work.

The tour says nothing about the Whitney family, other than they immigrated from Germany in the early 18th century. We visit their house, but it is unfurnished and open for visitors only on the ground floor. In comparison with the New Orleans mansions, this is a modest dwelling, rustic. Initially, I found it strange not to display anything about their lives: no pictures, no family history over decades of this plantation, and even the interior of the big house is not restored. But now I see that this was deliberate: the curators chose to direct their lens only on the lives of the enslaved people; they did not want to humanize the Whitneys.

On the drive back to New Orleans we encounter a familiar landscape of rolling hills, flat meadows and forest. We also pass several large industrial chemical works, two gigantic oil refineries and several smaller ones. In the refineries, the metal towers of many different heights look like music notation of some kind.

Philip found us a parking space in a nearby garage through Spot Hero for about half of what the hotel would have charged us. We have a terrific dinner in a tiny African restaurant on Royal street at the far side of the French Quarter. On the way, we pass a wedding parade, very similar to the classical New Orleans funeral parades. The bride and groom lead the parade. The passersby smile, clap their hands, some swing to the rhythm of music. The wedding party disappears in a restaurant. This is a long walk for us after a day of walking, through the full length of Royal Street. Our feet and hips cooperate beautifully.

Walking back, we find Bourbon Street transformed. It is always lively and loud, but tonight the streets are wall to wall filled with young people who are loud, coarse, and ready to get drunk. And big, very big, sometimes enormous. Deafening rock music blasts from club after club. It feels like Pamplona during the running of the bulls, minus the vomit on the streets. But it is only 8PM, the night is young. This ruckus is probably related to this Saturday being both part of a three-day weekend and the last one before the spring semester starts in most colleges. Tour groups at almost every other corner. These tours are thematically about death, voodoo and vampires. For some reason that theme has become a tradable tourist commodity, in addition to eating, drinking and listening to jazz. We run away as fast as we can.

Sunday, January 15: Cajun tour and towards Mobile, Ala.

Mobile, Alabama, is our final destination today. Once out of New Orleans, we drive on a flat and largely empty highway toward a guided boat tour of Cajun marshes. (The word Cajun derives from an old French word I do not remember, which denoted the French Canadians who moved here from the north in, I think, 19th century. They were animal trappers and fur traders, having lived in the isolation of deep northern forest for maybe two centuries, and speaking archaic French, hard to understand even by the 19th century Canadians. Many settled here into a new form of isolation and wildness in the alligator-infested New Orleans marshes.)

The flat boat flat accommodates about 20 people. Captain Jamie is a stand-up comedian. He tells us to avoid falling overboard because the tripmates will certainly not try to rescue us but instead will pull out their cameras. And if a poisonous snake enters the boat, to pass it around as a curiosity but not to him, as he has seen enough of those. Captain’s stories and especially his perfect delivery keeps us laughing much of the time. But he is also a serious man with extensive knowledge of the eco system of these bayous. I ask him many questions. We spot many alligators, mostly small ones but also one large one, birds and tortoises.

This, like many other boat canals here, were created by petroleum companies as the refining industry grew. Before that, a jungle and very tall grasses and small irregular water bodies occupied this land. I can appreciate the wildness of Native Americans and Cajun families living here, where nobody else would venture, in these treacherous grasses, muds and waters. It is easy to understand the epidemics of mosquito-related yellow fever and malaria in these parts, which drove away the French and Spanish occupiers. We learn that many famous movies situated in marshes and wild forests were filmed here. I can easily imagine “African Queen” with Katherine Hepburn being among them.

Another interesting observation are the trees, mostly live oaks (very different from northern oaks) and southern pines (of which the floor of our Wellfleet House are made). The tree branches are covered with vine-like Spanish Moss, which hangs like grapes but have a fluffy and soft and silky texture. I wondered if these are parasites, but Captain Jamie says that this plant meets all its nutritional needs from the air. Spanish moss has many uses, most of which I forget: as house insulation, and mattress and cushion fillers. The canal culminates in a dead end but we can see beyond the trees and grasses the tops of barges and ships, indicating a large canal nearby.

After the tour we explored the nearby settlement consisting of mobile homes, some beautiful homes, mostly on stilts; the hurricane surges can be as high as 6 feet and these houses are probably all raised to protect them against the floods. We found a restaurant which was surprisingly sophisticated, where we had a light lunch. We started driving the 2.5 hours drive to Mobile, which turned out to be longer than we expected.

The drive to Mobile takes us back through New Orleans, across the Mighty Mississippi. The outskirts of the city, like all large cities, feature industrial and commercial bric-a-brac. But here, we also see many human settlements in mobile homes. We also see several vendors of mobile homes. This must be how a lot of people in these parts live. And of course, the inevitable Dollar Stores punctuate our drive. At some point we get off the monotonous highways and take a scenic route. First, it ran through marshes as far as eye can see, soft tall, dreamy grasses, crisscrossed by creeks, rivers, ponds, flat and flatter.

Now we drive along the Gulf. Pristine white beaches, empty at this time of the year, are only yards away from the road, with no dunes in-between. We are at sea level. It is easy to imagine how this road floods, time and again, during storm surges and tornados. Hurricanes are the markers of time passage in people lives. People say: “I settled here shortly before Katrina”, or “we bought this house after Frederic”. Houses on the other side of the road, very close to us, have been raised on tall cement columns. The space underneath is used for car parking. We pass mansions under magnificent live oak trees.

It is getting dark, so beyond Biloxi we go back to the highway. Our Renaissance hotel in Mobile, next door to a convention center and two other high-rise hotels, is huge, cavernous, and nearly deserted. But somehow it is able to keep some measure of warm and coziness. We have dinner in the hotel restaurant, almost empty. Afterward, on our way to the room, we encounter a saxophone player in the lobby who plays the best music we have heard in days.

Monday, January 16, Mobile

It is MLK Day and we are in Mobile, Alabama! At breakfast, we are the only people in the dining room. Not much is going on in this enormous space designed for conferences of thousands of people. It is warmer outside than in the past two days, and cloudy. The name Mobile derives from Mobile Native American tribes who lived here. Mobile was founded in 1702 by the French as the first capital of Louisiana.

We take a walk down Dauphine street, the city’s commercial and entertainment center. Very quiet, maybe because this is a holiday. This long street looks like it was once a thriving center of urban life and commerce: many large, solid buildings, similar to the old NY department stores, smaller residential building echoing some of the New Orleans architecture.

But many storefronts are boarded up. We later learn that Mobile, with its large port, ship buildings and trade, was once a wealthy commercial center, but later suffered a major decline.

We are heading to the noon rally at Cathedral Square celebrating MLK’s birthday. We walk past the square to see the city, then back to the square. What strike us are the many murals, some really interesting, next to often vacant lots.

Philip takes a position on a bench while I go across the street to a café, which aspirationally offers “full tea service”. The place is full for brunch, but all I want is a cup of tea to take out. ‘Well’, the nice woman says, ‘all we have are big pots of freshly brewed tea for two for $16. But I will try to get you a takeout cup’. She disappears and returns maybe 5 minutes later with a styrofoam cup of tea. Then she types $16 on the register. ‘Wait’, I say, ‘you gave me just one styrofoam cup of tea!’ ‘Ok’, she says with a smile, ‘so it is half price’, and she types $8. We are both looking at the tea in a moment of silence. ‘You know’, I say, ‘tea at the Ritz Hotel in New York does not cost $8’. Silence. Then I look her in the eyes and ask: ‘would you pay $8 for this cup of tea?’ She smiles and without a word types $4. Now we are in business: I pay, we both smile warmly, I leave.

In the meantime, Cathedral square slowly fills up with mostly black people. A band starts to play on the podium, and a large contingent of people arrive from some organized march through the city. Earlier we made a bet about how many white people would attend; and it was really disappointing how few showed up. The celebration started with fiery speeches and music; but the real spirit is not quite there; the crowd is not very big to begin with, and when a misty rain arrives, people start leaving. The speakers are minor local officials and celebrities, not that interesting. The Mayor does not show up. The most passionate is the young lead singer of the band who mentions the high crime rate and challenges the crowd with “what is going on here? Where are we heading?” But that fires up only a few people.

On the other hand, the people are very nice, several greet us, some of them come to socialize, never mind MLK. Halina takes made a picture of a group of women on a happy outing (Philip quietly entered the frame, unnoticed).

We go to the history museum. Mobile started as a French trading post, then a military fort in the early years of the 19th century. It flourished in the time of big cotton plantations, mostly as a harbor for trading cotton and for imported goods. Later came shipbuilding. Around 1840 it was one of the biggest ports in the US. During the British invasion in 1812 the Spanish, who had deep roots in that area, joined the US and helped push out the British from the South. The fort was very useful. We learn that its best years were in the mid-1800s, based on the cotton and slave trade, and imports from around the world. The cotton from the plantations to its north was shipped from here all around the U.S and the world.

The civil war divided the city; but afterwards it flourished again. In 1901, new segregation laws came into force as part of the reconstruction and Jim Crow. After the Civil war, the city had several declines and revivals, the latter linked to the defense industry and ship building. But the overall trend was downward. The city began to decline after WWII, and although the U.S. civil rights wars in the 50s and 60s were not especially bloody here, the decline continued until it hit the bottom sometime in the 1970s. The city actually defaulted on its debts and was taken over by the state. It is currently on a slow upward trajectory toward recovery. In recent years, other industries moved in – space, chemicals, paper mills, harbor commerce, and four colleges (the biggest employer in the city) – and Mobile is slowly reviving.

We spend most of the afternoon in the museum; and also visit the nearby replica of the early fort; with its military history exhibition. Dinner at a nice nearby place with Spanish food. This place could have been in Boston: bright, light, filled with fashionably dressed waiters and guests, well-prepared contemporary cuisine. No tourists. And no black people.

On the way back, we spot an inviting-looking pub-billiard place that is going to have live music later on. So we return around 9:30 to a warm gathering of pleasant looking locals, with a country music woman vocalist on the stage. Right in front of the bar a man accosts us with a sad story of being temporarily impoverished. In his telling, he is an artist, a keyboard player, and we notice that the bicycle he is holding is a very fancy model. I want to get rid of him so I tell him that if he indeed played music for us, that would justify giving him money. I thought that that would end the conversation, but to our dismay the man turns around, runs into the next-door bar, and returns with a keyboard! He is actually planning to set it up here on the sidewalk and play! It is a chilly evening and the prospect of standing here in the street is not very appealing. I give him a few dollars and that is the end.

Everybody in our bar is white. Next door is another bar, all black. We order Bourbon and start a conversation with friendly and very cultured-looking bar tender about Mobile, then and now. He is a local, ‘born and raised’ and tells us about the city. Before long, a youngish woman joins us and the conversation gets quite intense. She introduced herself as Meredith Hayes, a clinical psychologist with a private practice, with a Ph.D. A very pretty woman, excitable, sincere, emotional, open. I cannot tell if she is who she says she is or if she is maybe nuts. She tells us about her husband musician and her two little daughters, about her Lithuanian forebears, about her stay in the Netherlands during graduate school, but the conversation gets deeper when she tells us that her doctoral dissertation was about how people coped with death during the Holocaust. In the end she gets ready to leave and insists on buying us another drink, which we energetically refuse. We make plans for lunch the next day (We never heard back from her).

On the way back to the hotel we see more signs of nightlife that we expected. I guess Mobile is indeed coming back to life.

January 17, Tuesday: Mobile and towards Hattiesburg, MS.

The highlight of today is the African Life Tour. It is designed as a two-hour group event but in this off-season, we are the only guests. Our guide Eric is an attractive black man in his 60s, with deep intelligent eyes. Eric is part of a local NGO which is active in reconstructing the black history of Mobile, identifying meaningful monuments, installing markers, conducting research, and organizing tours.

He takes us in his SUV on a trail of black life in Mobile. The tour takes 3.5 hours and at the end of it we are both exhausted from trying to absorb all we have heard. I cannot repeat all we heard but the essence of it is Eric’s comment that the black community in Mobile is living again through a period of another reconstruction. Later on I read in Wikipedia about reconstruction and conclude that what Eric means it this: After the period of relative renaissance and social and political gains since the 60s and 70s, the blacks in this city, and the state of Louisiana, have been getting increasingly marginalized, essentially repeating the trends of the original reconstruction that ended with Jim Crow era. The essential difference is, however, that the black community are much more self-confident and smart about using the instruments of law and market to fight this fight. And they are doing it again, as we speak, reconstructing again. Maybe this is the last reconstruction?

And then, Eric retells the story of Clotilde, the original reason for our trip to the Deep South. He tells us of the relationship between the wealthy landowner Maher and captain Foster, that the latter could bring 100 new slaves from Africa, a highly illegal act since 1808; how captain Foster in 1860 bought 120 slaves in west Africa on the assumption that only 100 would survive the passage (all survived); how he avoided being caught by US marshals (who knew of his trip and waited in the harbor) by transferring the 120 or enslaved people into paddle boats and landing them on the property of the Maher family, far from the Mobile harbor. He shows us Africatown, a small residential community in deep despair, its cemetery, its little bungalows, the large industrial plants that completely surround it. He talks about the population decline in the community, from 120,000 at its peak to 1600 today, and about the food desert that Africatown is, where one has to drive six miles to buy a bottle of milk. He talks about the efforts to renew that community, including the reconstruction of the recently found at the bottom of the river the Clotilda and constructing a museum on the site.

As we drive toward other landmarks, he tells the past stories of prominent black residents of Mobile, who became doctors, pharmacists and other professionals, and about all-black schools and Catholic nuns who supported the fight against institutional racism. He shows us the public library for blacks, which is tiny in comparison with the library for the whites. He talks about the Jim Crow days. We learn a new expression: urban removal, a take on urban renewal whereby houses get torn down to make room for new neighborhood, but the neighborhood never materializes.

These stories are great, he is a master of storyteller. But in the end I still do not understand what today’s whites are so afraid of that they try to push the blacks here toward the margins. We walk away from the tour with our heads spinning, grateful for an outdoor table in a neighborhood cafe and greatly relieved that our acquaintance from last night has not followed through with lunch together.

We cancel the plan to visit the battleship Louisiana and drive out of town, through Mississippi toward Hattiesburg; about a two-hour drive.

Wednesday January 18. From Hattiesburg to Natchez, MS

We sleep late; it is warm today. We find an uninspiring breakfast place near our hotel; pack up; and leave Hattiesburg. The previous afternoon we saw a glimpse of the town; this morning we see parts of the University of South Mississippi campus only from the distance. We take a quiet highway first to the north and then to the west; rolling hills, beautiful green, next to ugly mobile homes, endless displays of mobile homes and used cars for sale, and then finally green hills with occasionally a house here and there, in its quiet isolation. It is unclear how people make a living here; there is no visible agriculture; only logging. Out of curiosity we stop in a place called Prentiss; but that place is basically a display of poverty: empty front stores, paint peeling, trash, petrol stations, lack of regular stores. We quickly drive to the next town Monticello, where it is not much better.

We decided the previous day that we would take a walk in one of the national forests marked on the map. Plenty of trees around but finding access to a forest is unclear. We find an unpaved side road that leads us along a few isolated, really isolated, houses in the woods, further and further away. There is a secondary side road closed to traffic, sandy and muddy but doable. We park the car and take a lovely walk on this warm and sunny day. This is a logging area, with large patches of clear cuttings. Lots of cut-off side branches and mounds of stacked up trunks. Now it is clear why entrance to this national forest is not marked: this is a logging forest, probably not intended for recreation.

We enjoy the outdoors, but we also have a nagging feeling that we cannot entirely trust this place. Maybe someone will vandalize our car? Maybe some armed men from these isolated cottages will show up? We turn around sooner than we want.

We reach Natchez around 3:30-4pm, early enough to explore the city. We are staying in a B&B guesthouse, an old mansion filled with beautifully preserved antique furniture and rugs.

Without unpacking or cleaning our muddy shoes we hit the road again, walk a few blocks towards the mighty Mississippi. Natchez sits on top of a very high bluff; imagine the view of Palisades over Hudson river, but twice as tall and wider. We walk down the steep ramp to the shore, where there is a casino and another beautiful view. In the past, during the heyday of Natchez, the city was clearly divided into a genteel upper part and the lower part of casinos, saloons, and houses of ill repute. Walking back up is a challenge. Up again, we stroll the charming streets of boutiques and small shops. It is hard to tell if these are for the locals or tourists, as there are very few people on the streets at this moment. And most restaurants are open only Thursday-Sunday.

We find an appealing and very simple place “Rolling River”: by the locals and for the locals. People in this restaurant are very friendly, all skin colors and appearances. Upon entering the restaurant, they greet everybody with “hello y’all”. Unthinkable in the Boston area. The food is also excellent.

Thursday January 19, back to New Orleans

We wake up in this beautifully decorated room with an ornate bed, very high ceilings, and heavily draped curtains. Breakfast is indoors but separated from the outdoors by a glass wall. After the heavy rains and thunder of the previous evening the sky is clear, sunny, and inviting. We walk the nearby streets and admire the mansions. Their whiteness sparkles in the morning sun. In the early and mid-19th century Natchez was a major center of commerce, at some point even boasting of being the second in the country, after New York, in the number of millionaires. Today, it is a sleepy town, population 13,000, with charm, beauty, and a great collection of southern mansions, more impressive in my view than New Orleans. All of it was built on the backs of enslaved people.

As soon as we exit the city, the landscape changes into the usual American ugliness: the geography of nowhere, with one-story commercial buildings, car dealerships, and the inevitable Dollar Stores. The plan is to return to New Orleans, through Baton Rouge, by afternoon.

The trip to Baton Rouge and back to New Orleans takes us through the beautiful rolling hills with some forests, on a nearly empty highway. We have coffee at Audubon Cafe and refuel the car in a little village called St. Francisville, where Halina inspects an enormous antique store while I buy fruit in a supermarket. From there, the landscape turns industrial, with refineries in the Baton Rouge area. Baton Rouge’s distinction is the high concentration of refineries and chemical factories, and it used to be called cancer alley. We pass an ExxonMobil refinery: enormous, like a small city. It is a strange feeling to see in the physical reality the thing of articles and debates: the big bad and ugly heart of the petroleum industry.

The final stretch to New Orleans is easy, uneventful, and familiar: marshes, Lake Pontchartrain on the left; the airport; the Superdome, and our original hotel, International House. Philip returns the car and comes back by the little streetcar. It is nice to be in a familiar hotel.

At the bar, while drinking our welcome drink French 75 we chat with other tourists who recommend places to eat and listen to live music. We do not follow these recommendations because, as usual, something does not fit: either too far, or, like the music place, requires getting a ticket for a show, or presents itself as a pretentious “fine dining”. We walk through the French Quarter where we find a restaurant to our taste: not overly pricey or pretentious; nice food and drinks; and just right for our last evening. We stroll down Bourbon Street, which is crowded and noisy, with music blasting through open doors of endless clubs and restaurants. A little boy, no more than seven, sits on a curb, drumming on two upside down large plastic buckles. This boy is really good! I notice an inconspicuous woman sitting on the pavement nearby, leaning against a building, watching him. This is clearly his mother. We stop in the same courtyard where we were the first evening: the same band although with a different pianist. We really enjoy their laid-back style of singing old songs. This is the only place we like on Bourbon Street.

We turn into a side street to avoid Bourbon Street and unexpectedly come by a little café called The 21st Amendment, with live music. It has the atmosphere of a club, with guests smiling at each other, chatting. We also chat with the Australian couple at the next table. The musicians are young guys, full of joy and fantasy: a leading saxophone, a trumpet, an acoustic guitarist and a bass player. The saxophonist and trumpeter are also singers, and the sax player is the soul of the band: funny, emotional, connecting with the public. They are superb in every way. For me, this is the best jazz performance I have ever attended. It changes my attitude toward jazz, which I have come to see as a display of virtuosity without melody. These guys combine both.

Friday January 20, Going home

We have a couple of hours this morning before going to the airport. After breakfast we take St. Charles street towards the Mighty Mississippi. It is the perfect finale of this remarkable trip.