Welcome to this quick and dirty overview of resources and ideas for teaching Anne Bradstreet with digitized material. The material here was discussed at the “Textual Editing and the Future of Scholarly Editions” conference May 25-26, 2021. Specifically, these are tools to allow students to work with texts of the 1650 and 1678 imprints as well as the “Andover manuscript.” Please do not hesitate to contact me with any questions or comments at meneuman [at] clarku [dot] edu.

Links to digitization of early editions Anne Bradstreet

Tenth Muse (1650) 1 of 2

Tenth Muse (1650) 2 of 2

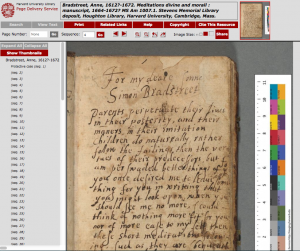

“Andover Manuscript” (1664-1672?)

Reading Bradstreet in the seventeenth century (three days in a survey class)

Day one, 1650 Tenth Muse:

Reading instructions:

You can’t read this book cover to cover, but you may want to focus in particular on:

- The title page

- Some of the dedicatory poems (the poems up until the Prologue on p 3)

- The Prologue (p 3)

- Enough of the four poems known as “the Quarternons” (pp 5-64), with special attention to the “Four Elements” and the “Four Humours,” which you may want to read in their entirety. (You also may want to look up what elements and humours are and how they were related in the seventeenth-century.)

- Don’t read cover to cover but take a look at “The Four Monarchies” (p 65) just to see what the topic and style is.

- Finally, just browse a bit in the final poems (pp 180-207). Just get a sense of the range of topics and styles. If you are curious, go ahead and read one of your choosing that catches your attention.

Lecture-discussion:

By first drawing out students’ experiences of reading in the 1650 edition, we covered the basics of the publication history and key issues of women’s writing, as well as close reading the title page and answering questions about what surprised them about early printing (accidentals, catchwords, etc.).

Day two, 1678 Several Poems:

Reading instructions:

Take a look at the front mater to see what is and is not different.

Pay particular attention to poems that are added after the 1650 edition. There are six poems that scholars think she may have intended (before her death) to include in a putative second print edition (maybe all those poems through “The Author to Her Book”?), and a bunch of other quite personal ones that the someone (probably someone in the family?) decided to add after her death. You might want to think separately about the logic of these two different “sets” of poems.

* Six poems were likely intended by Bradstreet to be included in a putative second edition of her poems. These appear after the last poem from the 1650 edition, “David’s Lamentation for Saul and Jonathan,” and include two elegies on the death of her father and mother, respectively, three religious contemplations, and finally “The Author to Her Book.” (Given our conversation on Wednesday, you may be interested to compare the Prologue in the 1650 edition and “The Author to Her Book” from the 1678 edition, which seems to refer to her feelings about the 1650 edition.)

* Fourteen additional poems were “made by the Author upon Diverse Occasions” and “found among her Papers after her Death, which she never meant should come to publick view; among which, these following (at the desire of some friends that knew her well) are here inserted.” (You can see this note on page 237 of Several Poems.)

Take a look at the “Elogy” to her at the end, if you wish.

I recommend the odd kind of apology poem that she adds at the end of the Four Monarchies, where Rome breaks off. See if you can figure out anything about her manuscript process and the relation between manuscript and print from this little poem.

Breakout discussion prompt (dueling Bradstreet apologies)

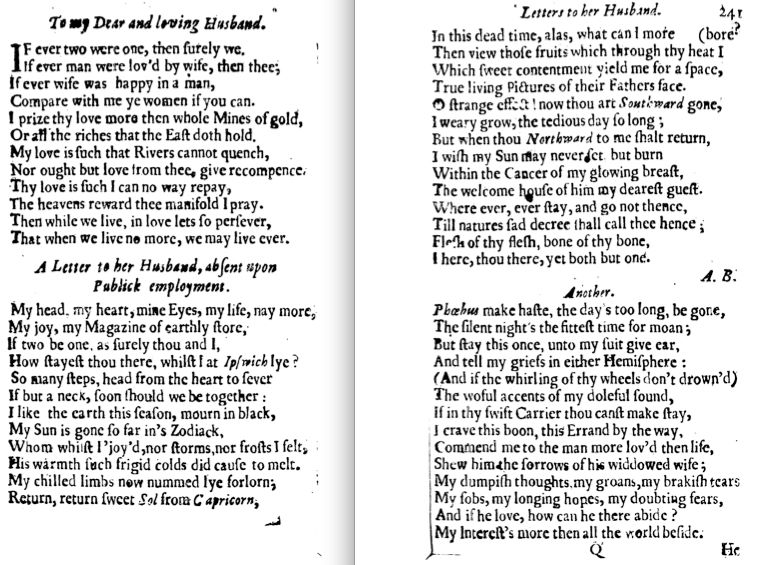

Look at Bradstreet’s “Prologue” in the 1678 edition (p 3) and compare it to “The Author to Her Book” (p. 216). Have one person read aloud as the others listen.

1. Paraphrase each poem in ONE sentence. (Put another way, what is Bradstreet’s thesis in each poem?)

2. Pick one of the two poems and go further. What expectations do they create? Does the rest of the book confirm or contradict those expectations?

Day three, Andover manuscript:

Reading instructions:

You are welcome and encouraged to read the prose, but we will focus mainly on the poetry. Get a sense of what kinds of topics she’s addressing in prose, in any case.

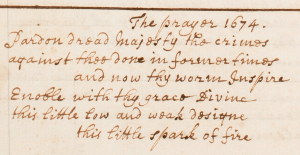

Anne Bradstreet starts this manuscript, but her son, Simon, continues is (that is to say, he copies in more of his mother’s writing in the book after her death). See if you can figure out where her writing ends and Simon’s begins.

Notice on how AB frames the whole manuscript. Keep an eye on how Simon continues the project and how he frames each poem.

Take a look at all the pages, including the markings made over time by various owners and readers (probably all family members) in the book. (Hint: They are not being jerks for writing in there.)

Now, because it’s going to be even harder for you to read 17th-c handwriting than it was 17th-c printing, here are a few poems that you can read online and think about:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50288/a-letter-to-her-husband-absent-upon-publick-employment

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43706/to-my-dear-and-loving-husband

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43707/verses-upon-the-burning-of-our-house-july-10th-1666

In fact, you might want to take a look at what poems are (and are not) included in the Poetry Foundation website. Don’t worry about the lengthy bio/introduction. Mostly just look at what poems are included. How might you read some of these poems differently if you only encounter them online and not in a 17th-c printed book or manuscript?

Breakout discussion prompt (How do we understand Bradstreet’s poems for her family?):

In your group, read the “A Letter to Her Husband” and “Upon the Burning of Our House” aloud.

Choosing one of the two poems as your focus, discuss where the poem first appears and how it is contextualized within the book or manuscript. How does the original framing/location of the poem affect how you read it? What is lost or changed if one were to read the poem only in the online version.

Bonus discussion topic (if you have time): Look to the full list of Bradstreet poems included on PoetryFoundation.org. (Scroll all the way to the bottom of the main author page.) As a group, decide on one poem from any of our three days of reading that was left out but that you would include.

Jumping into the Andover manuscript first (for a print culture seminar):

Reading instructions for the seminar session:

I would like you to read around in the text as much as you like, but I would also like you to read the book artifact, as well. What does that mean exactly?

Reading around: Scholars of book history might call this “discontinuous reading.” Essentially, it’s what you might do when you pick up a print magazine. Usually you don’t read every word front to back (which is likely how you approach a print novel, for example). Rather, you scan the cover and the table contents, you poke around, you start one thing but don’t finish it, something else catches your eye and you devour the whole thing, you flip back and forth throughout, you might reading in one sitting or in many. So that’s what I mean when I say “read around.” You might make an aim to read around for at least a couple of hours in preparation for class.

Reading the book artifact: This is a key skill to develop in any book history or print culture approach. Think not just about the text but about type (or, in the case of a manuscript, ink and handwriting), layout, the dimensionality of the leaf, apparatus in the book to help you navigate it (page or folio numbers, content lists), covers, marks, damage, design, etc. I suggest that you read for the text and for the book artifact simultaneously, though could also focus on one or the other in turn.

A few more point and questions to consider:

Anne Bradstreet starts this manuscript, but her son, Simon, continues it. (That is to say, he copies in more of his mother’s writing in t the book after her death.) See if you can figure out where her writing ends and Simon’s begins. Notice on how AB frames the whole manuscript. Keep an eye on how Simon continues the project and how he frames each poem.

Take a look at all the pages, including the markings made over time by various owners and readers (probably all family members) in the book. (Hint: They are not being jerks for writing in there.)

Take notes as you read around. Please have a good sense of YOUR reading of the text and the book artifact before you jump into the secondary reading:

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52.2 (2017): 389-422.

- Jordan Alexander Stein, “How to Undo the History of Sexuality: Editing Edward Taylor’s Meditations,” American Literature 90.4 (December 2018): 753-784.

- Meredith Marie Neuman, “Manuscript Culture,” A History of American Puritan Literature, eds. Kristina Bross and Abram Van Engen (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 259-274.

For my fall 2020 seminar, which was completely online, we broke the class period into three sections:

> For the first hour we discussed the readings and went over questions and comments about reading the digitized manuscript.

> For the second hour, I introduced the concept of paratext and gave them some basic terminology for thinking about the book object, especially leaf vs page. They then “read around” the digitized 1650 edition for about 30 minutes before coming back to discuss the reading experience.

> For the third hour, we broke into small groups. Half of the groups looked at the digitization of the 1678 edition, while half of the group looked at the digitization of the 1867 Works. Their objective was to think specifically about the ways the latter editions curated a particular view of Bradstreet. One student from each group talked through main points from their respective discussions, while another student from each group posted notes on the conversation on the online course management platform for all to review later.

As friends and colleagues know, I do a lot of teaching in Clark’s Archives and Special Collections. I am fortunate to have an amazing collaborator, Fordyce Williams, Archives Coordinator extraordinaire. Co-teaching a hands-on class like this is a lot of work but also extremely rewarding. Every semester we teach the course, we cap off the year with a Rare Book Open House, where students create an interactive exhibit with books mainly from the uncatlogued Jonas Clark collection.

You can read coverage of one of our early Rare Book Open Houses here.

Fordyce and I are particularly lucky to have an amazing collection of early books with which to teach courses like The Book in the Early Modern World, where students learn about early printing and book history hands on. Students do extensive lab work, much to the surprise of the humanities majors (English, History, Ancient Civilization, Art History, to name a few).

All of this has been made possible by a large collection of early hand press books donated by Jonas Clark, but the holdings of Archives and Special Collections contain many other wonders and rarities. This pdf of an article from the spring ’15 issue of Clark Magazine provides an excellent overview of collection highlights:

Historys Haven -Clark-Magazine-Spring-2015

The article is full of wonderful photos of books and objects (from miniature books to original Sigmund Freud letters to vintage gym equipment), some of which even I didn’t know we had.

Read the article online in the full issue of Clark Magazine here.

Every semester that I teach my rare books course, my students hold an Open House at the Rare Book Room at Goddard Library, which you can read a bit more about here. This semester the Open House coincides with our annual Academic Spree Day, which highlights all kinds of undergraduate research and creative accomplishment. If you are in the neighborhood, come on by:

Rare Book Open House

Wednesday, April 27

1:00-3:00

Rare Book Room, Goddard Library, Clark University

Then stick around for another bibliophile treat, as Dan DeSimone (Eric Weinmann Librarian at the Folger Shakespeare Library) gives the final Friends of Goddard Library talk of the season:

Learning Shakespeare at an Advanced Age

Wednesday, April 27

4:30 (with light refreshments at 4:00)

Jefferson 218, Clark University

Here is a handy map, in case you are new to campus.

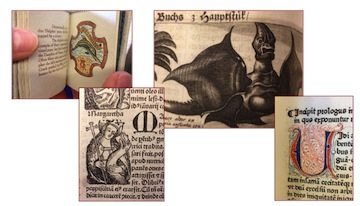

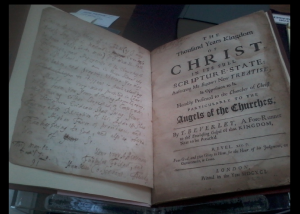

So come and celebrate celebrate William Shakespeare (on the week of the 400th anniversary of his death), and come check out some rare books from the Jonas Clark collection. I can’t promise any First Folios, but I can promise lots of interesting books, from rare incunables to modern miniatures. Here are some preview shots of the books my students have been working with this semester:

A belated update to my July 4th posting.

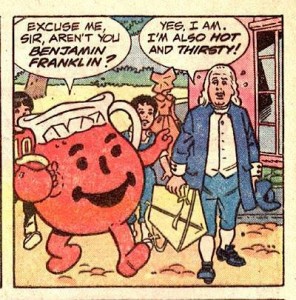

Okay. Realistically, most of you wont’ be as excited as I was to find out that there are competing attributions for the Franklin bashing Loyalist poem I posted on July 4th. So to give you a sense of how it feels, I am appending this completely gratuitous Franklin cartoon panel. Because stumbling across contradictory archival evidence always kind of feels like the Kool-Aid guy crashing through the wall. OH, YEEEEEAAAAAHHHH!

The Franklin poem has been attributed to multiple sources. Jared Sparks attributes the poem to Hannah Griffits, as does Milcah Martha Moore in her commonplace book. (See Milcah Martha Moore’s Book A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America, Eds. Catherine La Courreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf [University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997], 280n171.)

The confusion over the authorship of the poem is itself instructive. As Karin Wulf writes in her introduction to the Milcah Martha Moore commonplace book:

Moore and her circle were mostly loyal to the Crown, or objected to the war because of Quaker pacifist principles, but they were by no means a politically homogenous group. Two of Moore’s (and Hannah Griffitts’s) cousins were married to prominent, albeit moderate, Patriots, John Dickinson and Charles Thomson. Moore’s sister Margaret Morris, however, harbored the ardent Loyalist Jonathan Odell in her New Jersey home to protect hm from Patriots. Moore’s commonplace book reflects this heterogeneity. Loyalist Odell appears as an author alongside disowned Quaker and radical Patriot Timothy Matlack. Representing an entirely different view, Hannah Griffitts’s poetry espoused moderation and castigated extremism in any form. Thus the range of political opinions expressed in Moore’s commonplace book and the authors of those opinions, ranged from extreme patriotism to extreme loyalism. (38)

Indeterminacy can be extremely instructive, as in this case where uncertainty over the authorship of a single poem highlights an important point of how fluid political allegiance was, especially in the context of elite social networks.

OH, YEEEEEAAAAAHHHH!

My friends have been posting a lot of funny Franklin stuff this week, including that clickbait Benjamin Franklin’s Daily Schedule Will Make you Feel Worthless and some amazing remix images of Founding Fathers on DeviantArt, including everyone’s favorite FRANKLIN VS. ZEUS image. This is all particularly amusing to me, as I somehow find myself in Philadelphia for the July 4th weekend, and Franklin is everywhere.

My friends have been posting a lot of funny Franklin stuff this week, including that clickbait Benjamin Franklin’s Daily Schedule Will Make you Feel Worthless and some amazing remix images of Founding Fathers on DeviantArt, including everyone’s favorite FRANKLIN VS. ZEUS image. This is all particularly amusing to me, as I somehow find myself in Philadelphia for the July 4th weekend, and Franklin is everywhere.

I didn’t really plan it this way, but this was the best time during a busy summer schedule to take up a fellowship at the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Both places are closed for the long, patriotic, holiday weekend, however, and so I though I would share some Loyalist poetry that I’ve been reading.

This first piece is written in January of 1776 by an earnest Loyalist imprisoned in Philadelphia, presumably, for political sympathies:

Verse &tc

Confinement hail! in Honors justest Cause

True to our King, our Country and Our Laws

Oposing Anarchy, Sedition, Strife

And every other Bane of Social Life

These Colonies of British freedom tired

Are by the Phrensy of distraction fired

Surrounding Nations with Amazement View

The strange infatuation they pursue

Virtue in tears, deplores their Fate in Vain

And Satan smiles to see disorder reign

The days of Cromwell, puritanick Rage

Return’d to Curse our more unhappy Age

Rushing to Arms they madly Urge their Fate

And levy War against their Parent State

. We friends of Freedom Government and Laws

Are deemed inimical unto their Cause

In Vaults with Bars and Iron doors confined

They hold our Persons but can’t Rule the Mind

Act now We cannot, else we freely wou’d

But Calmly suffer for our Country’s Good

Success on Earth sometimes to Ill is given

To brave misfortune is the gift of Heaven

What man could do, We did, our Cause to Serve

We can’t Command Success, but We’ll deserve. Philada New Goal Jany 1776

The poem is on a single sheet of paper in Society Miscellaneous Collection, Box 13-B (Poetry and Music), Folder 2 (Local Poetry [early]), The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Like most of the poems in this wonderful miscellany, there is little evidence of who or when or why the poem was written and preserved beyond what is implied in the text itself. It’s nice to have a date and place of composition on this poem, but mysteries remain. The paper is folded (like many of the single sheets in the collection) in a way that suggests it may have been enclosed in a letter at some point soon after its composition. A little clue on the back of the sheet only adds to the curiosity, and I am posting a close-up picture of the notation to see if anyone can come up with a better conjecture than my fanciful notion: that it looks kind of like a shopping list, or perhaps request for some necessities from prison:

Detail from the back of Verses, &ct, Society Miscellaneous Collection, Box 13-B, Folder 2, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Click photo for higher resolution.)

I have not been looking for Loyalist poetry. In fact, I am trying very much to end my new book project (called “What’s the Matter with Early American Poetry?”) in 1773, just before the explosion of Revolutionary era poetry. But for some reason, as soon as I landed at HSP, it seems I could not avoid Loyalist poetry. I have been particularly charmed by this little common-place book:

Accounts of theatrical performances for the entertainment of British soldiers during the Revolution 1775-1780, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Click photo for higher resolution.)

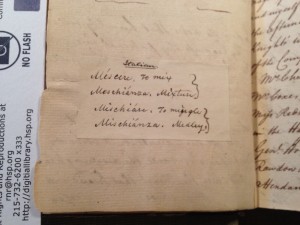

The section of “local” writing (by members of the compilers circle, it would seem) contains much poetry and prose writing that illuminates aesthetic sensibilities of elite Loyalists in Philadelphia during the war, including a long, first-person prose account of an elaborate all-day festival in British-occupied Philadelphia minutely planned by Major John André. (Read more and view objects related to the Machianza at the LCP Arts and Artifacts collection here.) Just before the 20-page account, the common-place compiler pastes in an etymology of the term “Meschianza” or “medley” from the Italian “to mix”:

Accounts of theatrical performances for the entertainment of British soldiers during the Revolution 1775-1780, f11v, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Click photo for higher resolution.)

Okay, on to the Franklin poem, which is probably why you started reading this post in the first place. But, first, in order to get the joke you have to know that the Franklin stove used an “inverted syphon” to draw heat and fumes down and up into the body of the stove. This would reduce smoke and increase heat in the room. (Well, that was the idea anyway. You can read a little more about the Franklin stove here.)

So here’s the Franklin poem:

Inscription

on a curious Chamber Stove in the Form of

an Urn, contrived in such a Manner as

to make the Flame descend instead

of rising from the Fire; invented by the

celebrated D.r Benjamin Franklin.

___________________________Like Newton sublimely he soar’d,

. To a Summit before unattain’d;

New Regions of Science explor’d,

. And the Palm of Philosophy gain’d.With a Spark that he caught from the Skies

. He display’d an unparallel’d wonder,

And we saw with delight & Surprise,

. That his Rod would defend us from Thunder.Oh! had he been wise to pursue

. The Tract for his Talends design’d,

What a Tribute of Praise had been due

. To the Teacher & Friend of MankindBut to Covet political Fame

. Was in him a degrading Ambition,

With a Spark that from Lucifer came

. He kindled the Blaze of Sedition.Let Candor then write on his Urn,

. “Here lies the renowned Inventor,”

“Whose Flame to the Skies ought to burn,”

. “But inverted descends to the Center.”

_______________

. Written by the Reverend

. M.r Jonathan Odell*

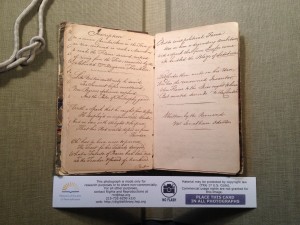

“Inscription,” Accounts of theatrical performances for the entertainment of British soldiers during the Revolution 1775-1780, f3v-f4r, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Click photo for higher resolution.)

Happy Independence Day, all!

Loyalist and Patriot alike.

*And, oh, hey. If you are tired of getting your Independence Day Kitsch on watching 1776 again (“Someone ought to ooopen up a window!” “Sit down, John!”), you could try The Scarlet Coat (1955), a kind of down payment on also kitschy AMC series Turn: Washington’s Spies that features George Sanders as Jonathan Odell.

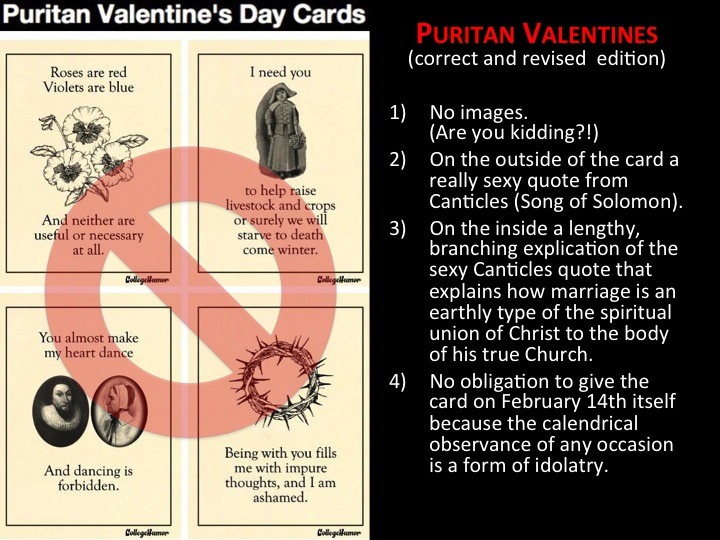

I love that people love to share Puritan humor with me. Cotton Mather is a particular favorite target of teasing. (Or perhaps I should say my own fascination with Mather is the target.) Every year around February 14, people start sharing those dour Puritan Valentine’s Day Cards from College Humor.

I appreciate the gesture, but I actually don’t really find them funny because they are not really about Puritans. Rather, they are about a caricature, and caricatures of caricatures are just a kind of feedback loop. (Except for that one card about “I need you to help raise livestock and crops or surely we will starve to death come winter.” That one is amusingly accurate about the domestic arrangements necessary not to perish in seventeenth-century New England.)

So today I am offering my instructions for creating real Puritan Valentines:

And if you don’t have the patience to make your own Puritan Valentine this season, try just reciting some of Anne Bradstreet’s poems to her husband. They are lovely and a bit sexy.

My head, my heart, mine Eyes, my life, nay more,

My joy, my Magazine of earthly store,

If two be one, as surely thou and I,

How stayest thou there, whilst I at Ipswich lye?

So many steps, head from the heart to sever

If but a neck, soon should we be together:

I like the earth this season, mourn in black,

My Sun is gone so far in’s Zodiack,

Whom whilst I’joyd, nor storms, nor frosts I felt,

His warmth such frigid colds did cause to melt.

My chilled limbs now nummed lye forlorn;

Return, return sweet Sol from Capricorn…

Happy Valentine’s Day, everyone!

Or not.

(You know, not impose any calendrical observance on authentic articulations of love.)

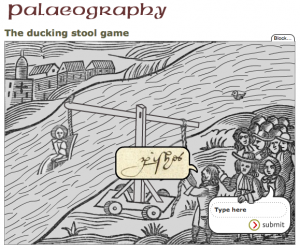

For several years, I have been creating paleography assignment for my book history courses. Well, when I say “creating” I really mean linking this excellent website with self guided tutorials from the National Archives. In addition to providing an informative introduction to reading early handwriting, the site offers interactive tutorials, examples for further practice, and a rather fun game where you try to prevent an animated woodblock character from getting dunked in the river by using your paleographic skills. (I will admit that even though I keep the poor woman from complete immersion, she was definitely a lot wetter after I completely botched a bunch of sixteenth-century letter forms.)

I know other teachers of book history who supplement this standard training with workshops where students make their own quills and practice writing with them. One day I will be that cool, but in the meantime I simply use as an excuse that my class usually meets in the Rare Book Room of the library, where pens, highlighters, and quill and ink are strictly forbidden. Instead, I have students explore the online Technologies of Writing in the Age of Print exhibit from the Folger Shakespeare Library. This excellent resource provides a virtual introduction the practical, embodied experience of writing in the early modern period.

Before this semester, my paleography units were fairly abstract, with students writing short reflective pieces about writing by hand and the experience of transcription. Some embraced the assignments and even looked for further opportunities to work with early manuscripts, but others found the training merely frustrating and were glad to leave it behind. This semester, however, I linked the introductory and training exercises to practical transcription work for my new seminar called “What’s the Matter with Early American Poetry?”, a workshop style class with an emphasis on non-canonical, obscure, and ephemeral verse production. I felt that students needed to gain confidence in reading early handwriting as soon as possible, lest they be intimidated when they encountered manuscript sources as part of their independent research at the American Antiquarian Society later this semester.

Because this class will mostly need to read seventeenth- and eighteenth-century hands, I streamlined the tutorial assignments and forgave them the sixteenth-century training. Then I uploaded digital images of pages from two very different verse manuscripts — the late seventeenth-century miscellany of a Puritan named John Dane, available in digitized microfilm from the New England Historical and Genealogical Society, and the early eighteenth-century poetry notebooks of Benjamin Franklin’s uncle and namesake, available in newly made digital images from the AAS.

The students working on the Franklin notebooks had a much easier time than those working with Dane. Not only were the images much clearer (you can even make out the texture of the paper itself), but Uncle Ben’s handwriting is neater than Dane’s, and eighteenth-century letter forms are much more legible to today’s readers anyway. Accordingly, I assigned each Franklin transcriber about four or five times the amount of text as I gave each Dane transcriber. Even so, the Franklin transcribers finished their portions in a fraction of the time it took the Dane transcribers to produce provisional readings with many places left undeciphered with a [??] for a placeholder.

Because students reported difficulties early on with the Dane in particular, I posted additional resources, including fun interactive game created by Laura Leibman at Reed College for her own early American literature students and these handy alphabet charts available through the University of Cambridge. I also included images and corresponding text for previously transcribed sections of Dane’s verse so that students could get used to his particular letter forms and various writing idiosyncrasies. In the end, one student not only managed to work though his two assigned pages but all twenty pages that were uploaded for the entire class!

Voracious transcriber, Tim Gunman (’16), poses with one of the twenty pages of John Dane’s manuscript that he managed to get though this week.

In class, we viewed the images together on two flat screen monitors in our well-wired seminar room. We talked through spelling oddities, abbreviation conventions, and the personal idiosyncrasies of our two versifiers. (Dane invariably writes “eth” for “the,” for example.) Several students showed how they had improved the legibility of the microfilm pages with simple image manipulation techniques. (Lowering brightness and bumping contrast helped quite a bit, as did reading the manuscript reversed out as a negative image.) Working as a group, we managed to decipher even those passages that previously had been unintelligible to individual readers. With transcription, the collaborative sum is usually more than all the parts.

Students were greatly encouraged by the session, it seemed, and gained some of the confidence that I had hoped they would find. They even agreed to return to their transcriptions and polish them over the weekend. One student in the class is our designated compiler and will will be preparing the work for a final check before posting as an open, online resource. Indeed, the prospect of making manuscript material more broadly accessible was perhaps the major factor in the success of the whole assignment. Already, several students are talking about preparing more manuscript transcriptions as part their final projects this semester. As one inspired student mentioned to me after class, the transcription itself is like a fun puzzle to figure out, but the idea of making otherwise obscure texts more accessible gives the whole process a sense of purpose.

Conquering seventeenth-century handwriting is a great way to end the week! Partially pictured and/or mostly blurry are Johanna Seibert (MA ’15), Sam Wallace (’16), Sarah Wells (’17), Laura Matthew (’15), et al.

As libraries continue to make manuscript collections available, opportunities grow for introducing paleography in the classroom. The next time I do my early American literature survey, for example, I just might assign — along with the standard anthology selections — some of Anne Bradstreet’s handwritten verse (via the Houghton Library’s digitization of the Andover manuscript) and a couple of Phillis Wheatley’s poems in manuscript (via the American Antiquarian Society’s GIGI database). Even in the survey classroom, there are opportunities to enrich our understanding of the many ways that texts circulated in earlier periods. Awareness of the prevalence of manuscript circulation in the age of print can only deepen our sense of the texts themselves.

The Bradstreet “Andover manuscript” is one of many such digitized resources freely available via the Harvard University library catalog.

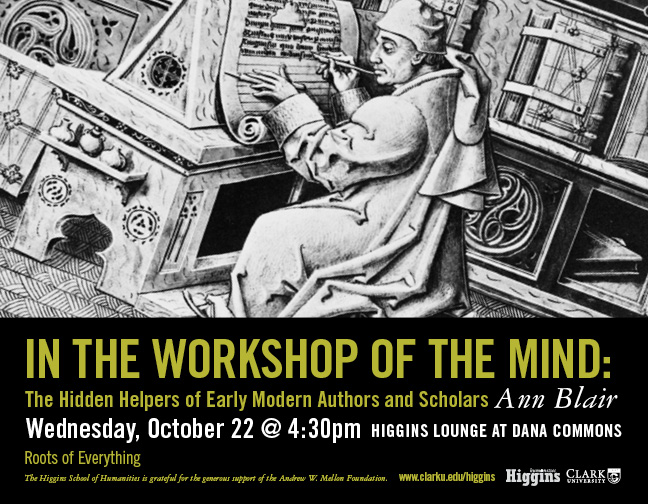

IN THE WORKSHOP OF THE MIND:

The Hidden Helpers of Early Modern Authors and Scholars

Description: Today we are well aware of the collaborative nature of intellectual work. The majority of scientific papers are co-authored; in the humanities, interdisciplinary initiatives and digital methods of research encourage collaboration. We have a general sense that such collaborative work is relatively new, that scholarship was a solitary activity in the past. In paintings and descriptions of the early modern period, scholars typically were depicted working alone. But the papers and letters that survive tell a different story, capturing how early modern scholars worked collaboratively through correspondence and in person with peers, patrons, and helpers (amanuenses, students, family members). Based on examples from paintings, manuscripts, and printed books, Professor Ann Blair will argue that collaboration was just as (and perhaps even more) widespread and essential to scholarship during the early modern period than it is in current times. Clark University Provost Davis Baird (Philosophy) will offer commentary.

The Roots of Everything is a lecture series sponsored by Early Modernists Unite (EMU) — a faculty collaborative bringing together scholars of medieval and early modern England and America — in conjunction with the Higgins School of Humanities. Supported by funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the series highlights various aspects of modern existence originating in the early modern world and teases out the connections between the two.

Ann Blair is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History at Harvard University. She specializes in the cultural and intellectual history of early modern Europe (16th-17th centuries), with an emphasis on France. Her interests include the history of the book and of education, the history of the disciplines and of scholarship, early modern natural philosophy and its interactions with religion. She has published Too Much To Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age (Yale University Press, 2010).

Wednesday, October 22 @ 4:30pm | Higgins Lounge at Dana Commons | Clark University

Free and open to the public.

Dana Commons is located on the corner of Florence and Maywood on the Clark campus in Worcester, MA. Directions to Clark, along with links to parking information and a campus map, can be found here. More information about the Higgins School of Humanities can be found here. Stay up to date with Higgins School of the Humanities events via Facebook.

Join us for an exploration of collaborative work in the early modern and contemporary world.

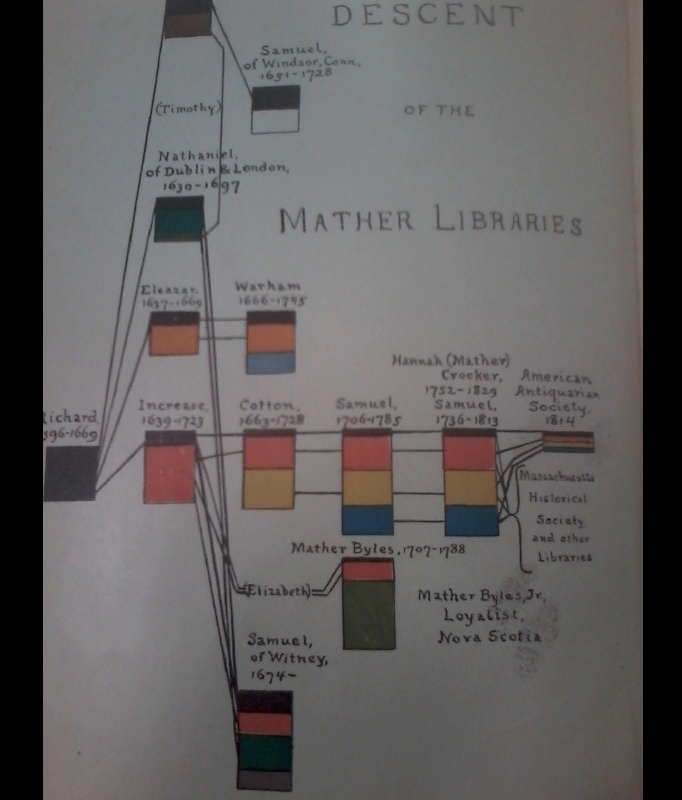

(This post is a slightly edited version of the talk I gave at the Society of Early Americanists “London and the Americas, 1492-1812” conference at Kingston University, July 17-21, 2014. The presentation was part of a round table entitled “Puritan Studies in Post-Americanist Times.” I am indebted to Tom Knoles and Elizabeth Pope at the American Antiquarian Society for an ongoing series of conversations and insights about the Mather Library collection.)

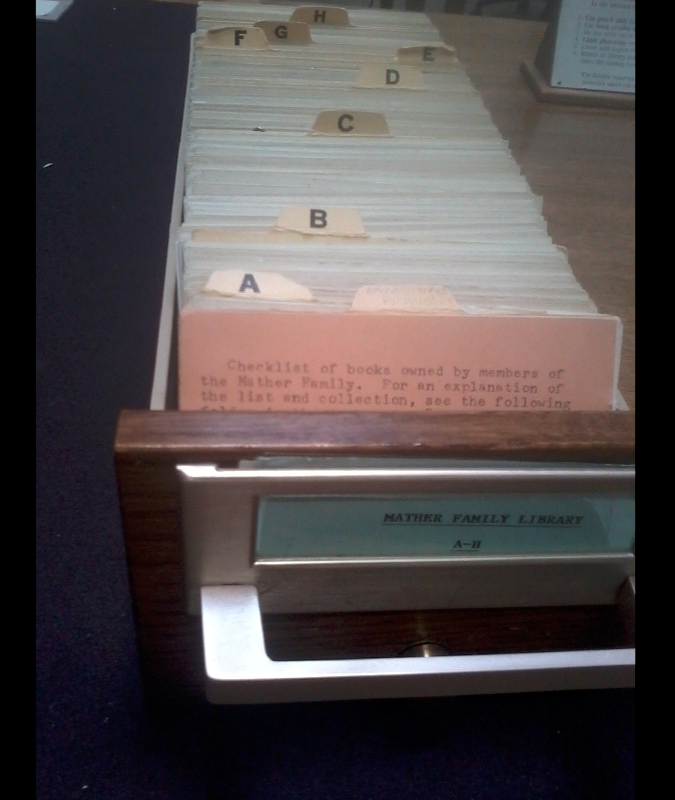

Let me start by showing you just one of many reasons why the Mather Library is such a headache:

Today we are concerned with the little striped block on the far right-hand side of the chart, which represents about 1,000 volumes spanning two centuries of Mather book collecting, many sold in 1814 to Isaiah Thomas, printer and founder of the American Antiquarian Society, by Hannah Mather Crocker, Mather descendant and an antiquarian scholar in her own right. Crocker gave additional volumes to the AAS directly. When Thomas gave the bulk of this collection to the AAS, he first assessed a value for each book, which he inked inside the front cover (“50 Cts” for example), and then compiled an index of the whole, arranging it by format—folios, quartos, etc. His inventory was a boon for future book historians, notwithstanding the errors and inconsistencies, vagueness of titles and authors, nor the fact that entire volumes of multiple pamphlets and other imprints bound together were listed simple as English Tracts 1, English Tracts 2, etc.

A full bibliographic description of the collection was not attempted until almost a century later. The color plate above comes from Julius Tuttle’s checklist, published in the AAS Proceedings in 1910. Tuttle’s list is alphabetical by author, with short, sometimes incorrect titles and (most helpfully) with indication of provenance markings, such as the names former Mather owners. (“Increase Mather,” for example, or even more often, “Crescentius Mather,” as he often inscribes his name in Latin.) Tuttle’s checklist is incomplete, in part due to idiosyncrasies of shelving and record keeping over time. Tuttle’s list also excludes (for the most part) continental imprints, focusing instead on American and some English printing. And there were undoubtedly other volumes that Tuttle simply couldn’t find. Some collections of pamphlets bound together at the time of the original gift, for example, migrated through the collections. Virtually all of these composite collections were disbound, making it hard to distinguish whether or not a single title was originally part of the Mather collection. In the twentieth century, many good souls worked to fill in Tuttle’s gaps, and if you ask at the reader services desk, they will bring you—if they can locate it—an annotated offprint of the Tuttle checklist with almost forty percent more entries handwritten on interleaved inserts.

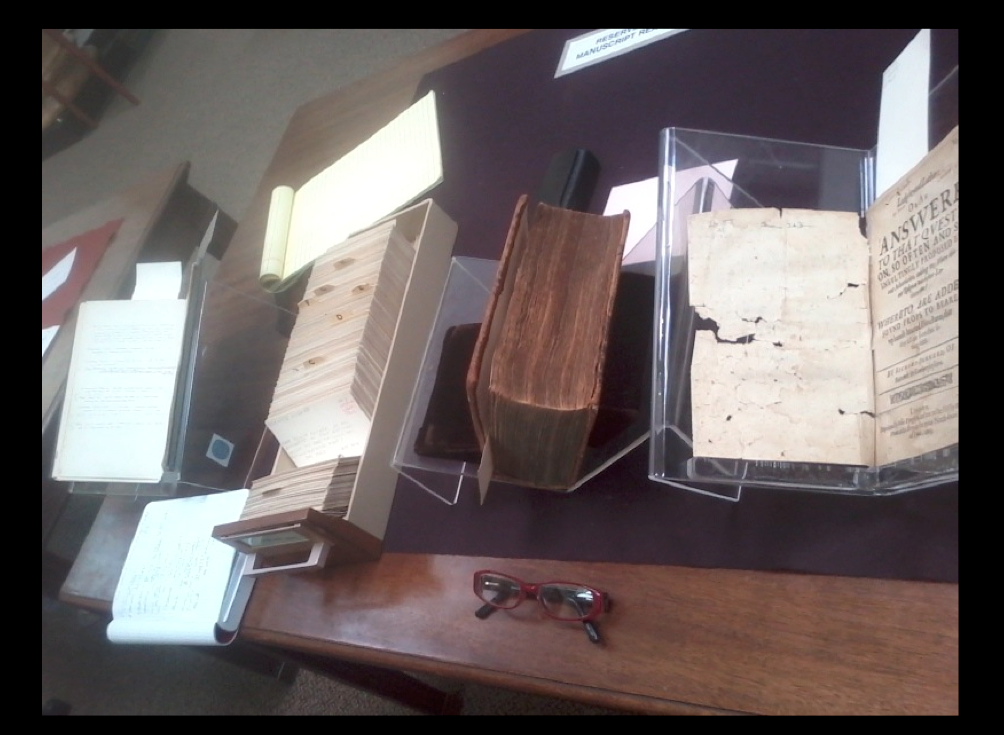

In the 1980s, head of reader services Keith Arbour compiled a card catalog which—while still incomplete—was substantially more comprehensive than the annotated Tuttle and bibliographically more precise. Again, if you ask at the desk, they will bring you out a folder of Arbour’s notes, including instructions to a woman (yet unnamed in my research) who assisted in writing out the cards in pencil. While still incomplete, the card catalog adds items not included by Tuttle, such as an eleven-volume manuscript sermon cycle on Revelations bought by Increase Mather in London in 1691. Arbour’s card catalog misses elusive continental imprints that have fallen through the cracks over two centuries of curatorial preference for American imprints.

In the Mather Library, fortunately, uncataloged volumes are relatively easy to locate. The current call number system—Mather Library 0001, Mather Library 0002, etc.—was determined by the order in which the books were on the shelves at the moment the Library decided that the old call number system (specific to the physical layout of the former library building) needed to be revised. With the new call number system, each item has a number, even if it doesn’t have a catalog record. So, in theory, if you generate a spreadsheet of the Mather Library catalog records by call number, you can simply look to see where the gaps are, and there you will find an uncatalogued book, most likely a continental imprint.

There is much more to say about retrospective conversion, the process whereby card catalogs are converted to electronic catalog records, almost always offsite, where no confirmation of bibliographic details is possible. The correction of Mather Library conversion records continues to this day. The American imprints seem to be in order now. One cataloger is just about done with cross referencing English imprints against ESTC (English Short Title Catalogue) records, and another has begun working through the continental imprints, though the many demands on her time continually interrupt progress. To date she has finished about twenty records. This process of correcting retrospective conversion creates a reliable record the essential bibliographic information: title, author, publication information, cross reference to external databases. It leaves out (for now, at least) owner’s inscriptions, reader’s marks, and other copy-specific features.

These copy-specific features, of course, are why I muck about in the Mather Library in the first place. One of my first finds in the collection, through nearly random chance, was a volume owned by Increase Mather made up of four titles by Hugh Broughton dealing with millenialist theory: bound together in a single thick but fragile volume, a mixture of printed texts and manuscript copies of printed texts, illustrations and fold outs, all heavily annotated by Increase Mather himself. I can make notes on extraordinary finds such as this—and I can catalog them in excel or zotero or whatever other software someone will undoubtedly recommend to me during Q&A—but there is no true metadata potential here until the fundamental cataloging of author, title, and publication is complete *and* until each volume is scruitinzed by very analog and clunky methods. Frankly, without major extramural resources, this work can never be done comprehensively. Only piecemeal by foolhardy enthusiasts like myself and anyone else I might interest in this Sisephean Task.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, though, we must stop to reflect that, as a collection, it is not clear what, exactly, the “Mather Library” is. We would like to think it is a glimpse of the accumulated intellectual history of multiple-generations of Mathers. And it is. But it is also impossibly idiosyncratic, as Tuttle’s chart suggests. Even if Hannah Mather Crocker’s portion was representative, which it may or may not have been, she was generous with her books. Just like others before in her family, she lent, gifted, and sold individual titles within her extensive Boston-area network. William Bentley, a Salem minister, visited the collection frequently and recorded with alarm in his diary that he found the collection “much diminished.” Does this mean, to begin with, that the Mather Library collection that Thomas snagged was, in a sense, remainders? Those titles of not enough interest to have been already carried away by 1814? Such a skew—the absence of books, we could say—might reflect not the collecting habits of the Mathers so much as the lively interests of early eighteenth-century ministers and antiquarians. Then, too, curatorial practice has preferred some imprints over others, deliberately or accidentally altering identity and meaning. The Mather Library—like all archive—is whatever we can get our hands one, whatever we can describe, whatever we can catalog. It is accidental, contingent, conjectural, murky. Just as we talk about ideal readers only to immediately complicate that notion, so, too, we might need to theorize the Ideal Mather Library and then trouble what we imagine that collection to be.

In the time remaining, I would like to show you some examples of how one might go about this project of conjecture. For the past few weeks, I’ve been looking at books owned by Increase Mather, volumes that he likely bought during his time in London from 1688 to 1692 where he was working to reinstate the colonial Charter. To make my task more manageable, I chose to focus only on the “B” section of the 1980’s Arbour card catalog, flipping through and pulling likely candidates based on handwritten indications of provenance information—a tiny “IM” penciled in the bottom right hand corner.

One goes to the archive to seek the kind of artifacts that intellectual historians dream about. For example, say you wanted to see how Increase and his son Cotton were influenced by Robert Boyle’s work. In this case, you would be very happy, finding in the collection a presentation copy from Boyle himself, as well as another copy with handwritten notes by Increase Mather indexing passages on topics like witchcraft and smallpox. These discoveries are what I call the Smoking Guns. They are incredibly wonderful and incredibly rare finds.

More often, however, you will find a copy—possibly with an owner inscription, possibly not—sometimes with marginal ink or pencil annotations, but usually no handwriting to identify and date, and no way of knowing if a mark is Increase Mather’s or that of some avid AAS reader from back in the days when, I suspect, people marked books in archives with impunity for the sake of their pressing antiquarian researches. All you can say about such copies is “this at one time was associated with the Mathers and now it lives here.” Let’s call these finds: the Blind Alleys.

And then, not infrequently, you find what you do not expect. Let’s say, for example, you’d like to trace the role of skepticism in Increase’s thought, or perhaps the sources that inform Cotton’s Christian Philosopher. You could pull up the Mather Library copy of Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici (bound together with two related titles not by Browne) and see that Isaiah Thomas valued the book at 50 cents in 1814. Accordingly you would know 1) that the book passed through Isaiah Thomas’s hands, 2) that it was associated with the Mather library, and 3) that it was roughly equivalent in value to any number of other books in the collection in the early nineteenth century. No Smoking Gun here.

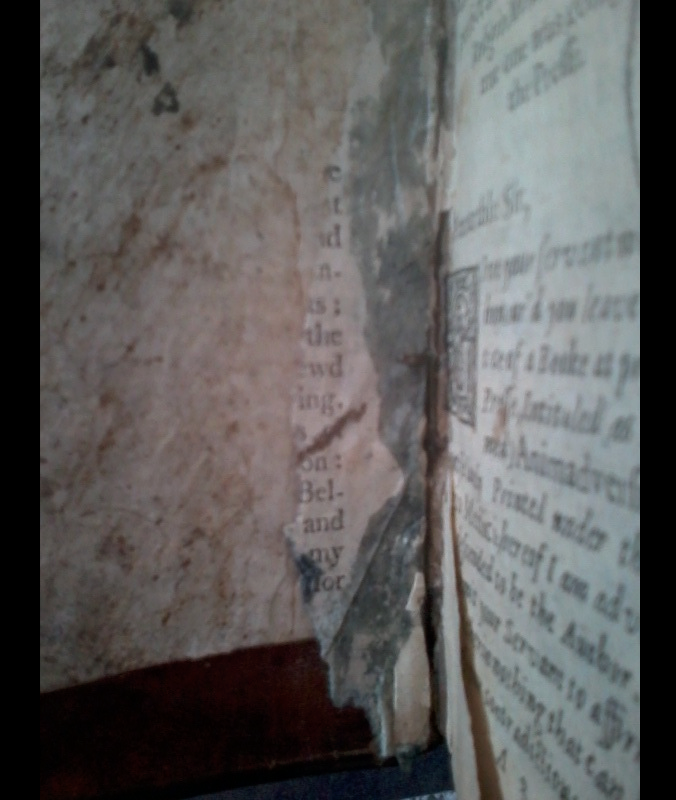

Then again, if you happen to look into the gutter, that place at the spine of the book between the cover boards and text block, you might see this:

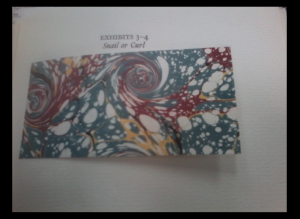

a scrap of printer’s waste paper, marbled on one side, used in some repair, probably in the very early nineteenth century, (as indicated by the Snail or Curl pattern of the marbling).

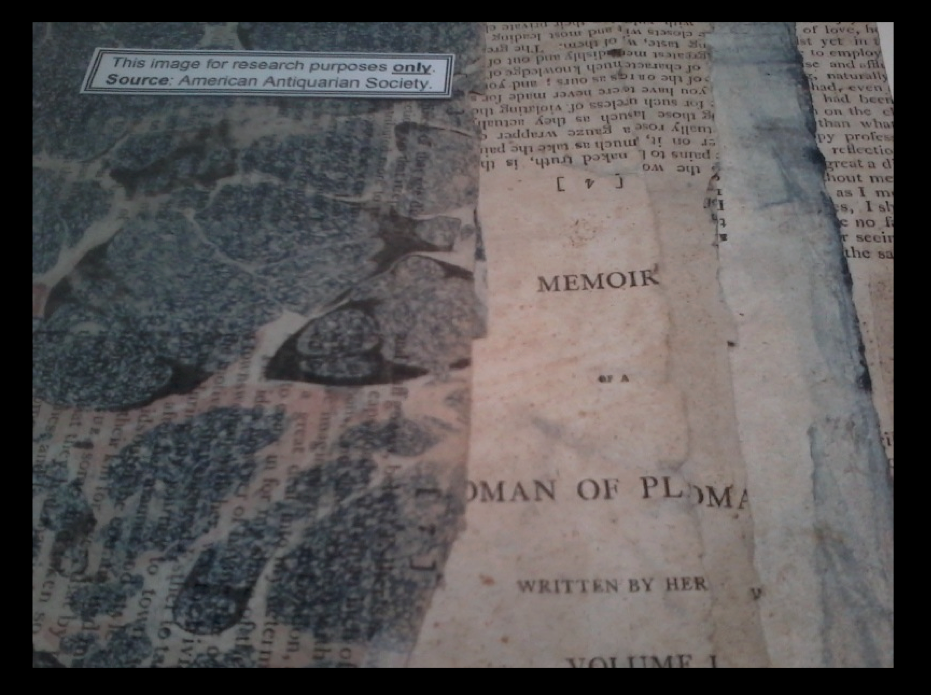

You might even recognize the distinctive black and blue coloring from other items you’ve seen and realize that this little scrap of paper in the gutter is a sheet from an illicitly printed copy of John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, or Fanny Hill.

This marbled waste paper appears not infrequently, especially in the AAS collections, probably because Isaiah Thomas’s binder, to whom he sent many books to be rebound and repaired from around 1812 to 1814, seemed to have a large supply of the stuff.

Hilarious juxtapositions abound, with the distinctive erotica covering printed material such as sermons (including a manuscript volume of Cotton Mather’s sermons in th Mather family papers)and even the Worcester County Court Records volume that recounts proceedings against several booksellers fined for selling other illicit editions of Fanny Hill. Because you can make out just a little bit of the text on the page, you can also determine that the marbled sheet in the gutter of the Mather Library copy of Browne’s Religio Medici comes not from the A gathering that makes up most of what is housed at AAS but the B gathering, as recently identified as Princeton Library’s Rare Book Division.

This is called Going Down a Rabbit Hole. It is both tedious and fun. It is provocative of much speculative thought, flights of fancy, as well as genuine theoretical reframing of book history and material textual analysis. It does not, however, tell you a lick about the intellectual sources of skepticism for Increase or Cotton Mather’s writing. It tells you only what you knew before: that the book passed through Isaiah Thomas’s hands and that it was associated with the Mather library.

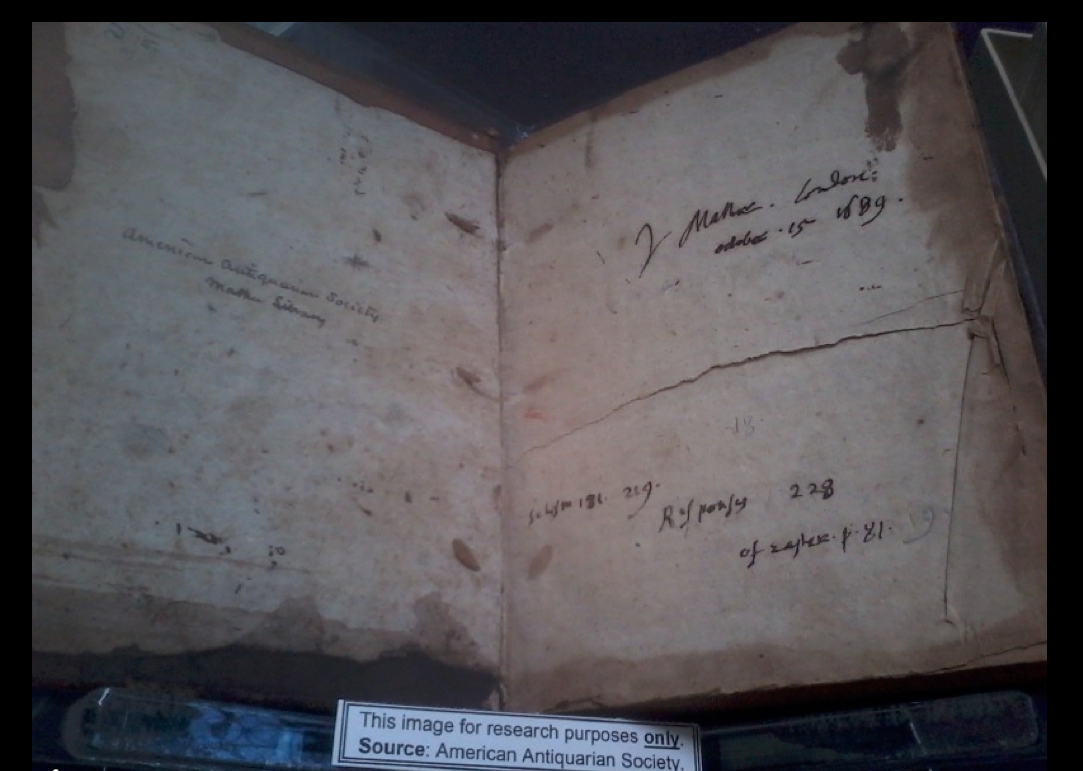

I’ll end with just a bit about Increase Mather’s acquisition of books while in London from 1688 to 1692, as this is what the title of my paper has promised. I began looking for evidence of book buying by Increase Mather in London and found a number of books (in the B section of the card catalog, of course) which Mather inscribed along with date and place of purchase, as in this 1689 copy of Richard Baxter’s The English Nonconformity (“I. Mather. London. October. 15. 1689.”):

I was grateful for the tiny Smoking Gun. Let’s just call this one a derringer, though, because the other reader annotations not nearly so interesting. The imprint is by Thomas Parkhurst, a non-conformist-leaning bookseller that had also sold Mather that uncataloged eleven-volume manuscript sermon cycle on Revelations that I mentioned earlier. In fact, Parkhurst’s name pops up again and again in the title pages of Increase Mather’s books. I think he shopped at Mr. Parkhurst’s a lot.

Mather also acquired a good number of books from authors directly. The Arbour card catalog fortunately records when books are inscribed “ex dono authoris,” a gift of the author, such at this copy of Baxter’s The Church Concord:

Now we can begin tracing out not only bookselling networks but the intellectual and social networks implicated therein. Parkhurst printed many of Baxter’s works. Baxter not only gave books to Mather but also dedicates a book to the New England minister. These book networks, simultaneously intellectual and material, authorial and commercial, are sometimes complex, as evidenced by this volume,

“ex dono authoris,” by Thomas Beverly, who gave a copy of his book to Increase Mather, as he indicates in this letter (now tipped into the volume in a particularly unattractive mid-century library rebinding) because Mather was the dedicatee of the work by Baxter which Beverly is attacking in his own book. I can’t help wonder how Increase received this gift. With interest? With irritation? With patience? A marginal note on the last printed page in Increase’s handwriting could tell us. A nice Smoking Gun that might exactly triangulate Mather’s position in a late seventeenth-century pamphlet war about Presbyterianism. But, alas, the note has been trimmed off in some rebinding effort sometime within the last three centuries.

This last piece of Semi-Smoking evidence should return us to questions about the nature of the Mather Library. Why is the Beverly work here? Because is was an important part of Increase Mather’s intellectual world in London, 1688-1692, or because it is a remnant, a volume not taken away by avid readers before Isaiah Thomas could get his hands on the lot. Might we complicate our conception of the Ideal Mather Library with realities of the Less Than Ideal Mather Library? Might we not give some thought to what is missing—the volume burned down in house fire, the one lent but never returned, the one never acquired. What role does desiderata (lists of books desired) play in Mather’s collecting? What role do our own desiderata play in our sojourns into the archive, where we must learn to be be instructed by the Rabbit Holes and Blind Alleys perhaps even more than we are by the Smoking Guns if we wish to understand what we are looking at and what we are looking for.

Another cool gloomy day. Cleaned up a little and ironed although there wasn’t too much and I caught up on my correspondence and got ready for work. Watched TV and got working on my rug for a while. Then I went to bed late. Steve K. died today.

Another cool gloomy day. Cleaned up a little and ironed although there wasn’t too much and I caught up on my correspondence and got ready for work. Watched TV and got working on my rug for a while. Then I went to bed late. Steve K. died today.

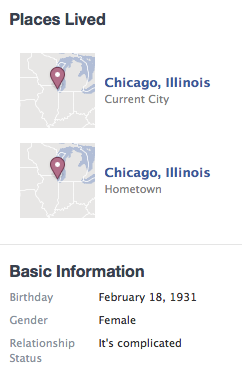

If you like the Samuel Peeps twitter feed (or if, like me, you like the idea of the Samuel Peeps twitter feed but you don’t actually keep up with it), or if you are friends with Isaiah Thomas on Facebook (but wish he would write in his diary more often), might I recommend that you become friends with Dolores Factoryworker immediately?

I accepted a Fb friendship with Dolores last December. I don’t know her last name (she isn’t saying), but every morning I check my news feed, if only to stay caught up on her diary entries. I can tell you about her daily commute to the Zenith factory in Chicago in 1960, as well as the diversions that she and her co-workers pursue in order to make time on the assembly line a bit less mind-numbing. Like many of her friends who met her last winter, I’m still wondering whatever happened to Jim-of-the-enigmatic-flirtations-and-mercurial-mood-swings. (Did he quit or get fired? What about the fiancée? Why all those months of mixed signals, Jim?) All her co-workers can run hot-and-cold sometimes, but I think we know by now who to trust and who to avoid. (Crabby Helen, you know who I’m talking about. And don’t think I’ve forgotten about you, Oddly-Doppelganger-Other-Dolores.)

Work was a war a[s] usual to keep up and I was losing all day. We did 60 an hour and brother! Larry came by and I asked him if he had his car but he didn’t. I told him I was going downtown and he said, “Oh, that’s why you look so nice.” Richard came by and told me all about his job and stuff. And Kenny helped me again. At lunch Mary broke the news to me that she became a grandmother Tuesday. She passed candy but she didn’t bring any down to me. Then it was finally time to go home and Jenny dropped me downtown but first we stopped at Fran’s house. I didn’t go up.

Dolores also keeps me up to date on her after work shopping trips to the National, her visits to Candyland, and the endless housework and ironing preparation for the next workday. (Boy she sure is tired.) I also keep up with current movies via her capsule reviews.

Went to the show and saw “The Gazebo” (lousy) and “Dog of Flanders” very good.

Sometimes she posts images from her favorites films (Pillow Talk, Beloved Infidel, and Ben Hur were some recent favorites), but she also post more ephemeral (literally) glimpses of her life outside of work: TV guide schedules, grocery store circulars, an ad for those nice soup mugs that Lipton sent her.

The doorbell woke me up and my cups from Liptons came. They were real nice.

Honestly, with all the ironing and cake baking (and now that new rug she is making), and all the days she’s wiped out and just sleeps all day and feels lousy or eats like a pig or stays up to watch the late, I just don’t know how she finds the time.

After I got downtown and went straight to the Palmer House to get my ticket and is it ever nice there. Then I went to the Walgreens for coffee and to the card shop and home. Uncle Joe was over and I told him about my trip and he wanted to go. Didn’t do anything and barely got ready for work and was so tired.

Over breakfast this weekend, my partner Danny and I found ourselves talking about Dolores like we would an old friend who we’ve been worried about lately. We’re both pretty concerned that the visits to the workplace nurse are becoming a daily occurrence. It makes no sense to us that her supervisor keeps putting her on more and more difficult assembly stations when her hand is clearly not yet fully recovered. Danny’s worried that they are trying to push her out, and so now I’ve got another thing on my mind.

Last day of work. When I went in this morning for my bandage the nurse made me see the doctor. He gave me some pills and said to take two a day. Helen is still crabby as ever and she got into a big fight with the stock boy and Ann. About 10 o’clock I started getting the most terrific backache and I was in pure misery the rest of the day. I was almost in tears by 3:30. Kenny and Richard and Larry came over to talk to me. Then Jo came and saw how awful I looked and helped me. I went for a drink and even Emmanuel asked me if I was tired.

As an early Americanist whose livelihood is based upon poking about in the private journals and notebooks of strangers, I find that this compelling archival recovery project hitting me particularly close to home. Instead of imagined subjectivities of Puritans and poetasters many centuries dead, I am eavesdropping on a woman who may or may not still be alive today. What difference does 400 vs 50 years make? I search Dolores’s daily entries for geographic markers of a city that I still call my hometown. I hear echoes of my own aging or departed midwestern female relatives in her colloquialisms and strangely muted accounts of a hundred anxieties and little victories. I empathize with her awkward cycles of preening and self-doubt. This summer I turn in earnest to the next book project that has me diving into a batch of private journals and reading cryptic accounts of lived experience. Let’s see if my friendship with Dolores brings any new insights to my archival methods.

Dolores has been informed by Fb that she has reached her limit of sending friend requests. No fear. You can initiate a friendship with Dolores yourself, and I highly recommend that you do so. Boy is she ever interesting. https://www.facebook.com/dolores.factoryworker