When I tell people that I bring students into the archive for hands-on work with centuries-old books, they frequently inquire how young adults respond. I tell them simply that students love the entire experience. The ubiquity of inexpensive modern editions of old texts and the rapid expansion of digital technologies make them more interested in rare books, not less. I am starting this series of student-written responses to the archive to allow them to talk about their classroom experience directly. In the first installment, Erin O’Kelly ’14 talks about our first session last fall, during which Fordyce Williams (Coordinator of Archives and Special Collections) and I showed the class how properly to handle old books. -MN

CARE VERGING ON PARANOIA

(a student perspective on learning to handle rare books)

by ERIN O’KELLY

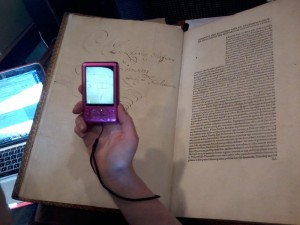

One of the least expected habits I developed in Archival Research class (aside from a tendency to immediately categorize nearby text as a serif or non-serif) was the way I came to handle books. The first day in Archival Research pretty much met my expectations; we were taught how to handle old or fragile books, coached on what to do or not to do with them, and then set loose under supervision to, at least in my case, promptly overreact and try to examine the books without in fact actually touching them. I’m sure it was entertaining for the responsible adults that first day to watch an entire classroom of students try to handle books without so much as breathing on them or looking at them wrong.

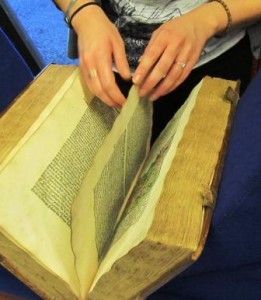

I’ve since realized that looking at a book incorrectly won’t hurt it and have since become much more comfortable handling old books. Experience has helped me to determine the amount of care and gentleness each one requires – when it’s okay to open a stubborn cover, for example, versus when I should resign myself to peering into barely-open pages in order to protect the spine. Sometimes a book really does need to be treated like spun glass and kept away from strong breezes or sudden sneezes; more often, though, a sturdy cradle and gentle handling are enough to ensure that a book will be kept in good health.

No books were harmed in the making of this blog post (though we did study existing damage in the collections to understand book structures better).

Now, if it’s a book, I treat it carefully. If it’s someone else’s book, I treat it even more carefully. If it’s someone else’s very old book, I treat it with care verging on paranoia. Imagine my surprise, then, when I realized that I was treating my new, inexpensive paperbacks with a level of care approaching that we use in Special Collections. Suddenly I was being careful to touch only the edges of pages when possible, turning them more carefully, and opening books with more attention to strain on the spines (which, given the iffy quality of modern glued spines, isn’t a bad idea anyways). It’s a pleasant side effect, having gone into the class expecting to learn how to handle fragile old books with caution and coming out learning how to treat all my books with care. Hopefully by the time the course ends I’ll be able to treat all my books well enough to have them reach the age of their Special Collections cousins.