Newsletter: November 2015

Annual Meeting/Member Appreciation Event

“Exceptional and Fascinating.”

“Left me with a desire to learn more about the Living Systems Lab”.

“Thoroughly impressed.”

“I learn something new each time I tour the site.”

This is what people had to say after attending the BRWA’s annual meeting on Sunday, November 8th, where Gene Bernat, CEO of the Fisherville Redevelopment Company, gave a presentation and tour of the Living Systems Lab (LSD) in South Grafton.

Gene explained that one of the LSL’s overreaching goals is to build community through participation in ecological remediation and restoration – in this case, the Blackstone Canal at Fisherville, which is highly contaminated by leaking underground tanks of oil, among other pollutants. It took over 200 years of industrial innovation, with best intentions for building communities but some unfortunate consequences for the environment, to arrive at the situation that the Blackstone canal and river are in. So it will take a complex, long-term approach of science, public policy, and community buy-in to restore this landscape to a healthy state.

More than anything, this approach will require a new cultural mindset of how we view the river as a resource. It will require hard science as well as social science. For example, before we shake our heads at the lack of foresight of mill owners, consider that these same water resources are now being contaminated with antibiotics and by personal care products containing plastic microbeads. We have to ask ourselves if we are any different than the mill owners, utilizing the river as a vehicle of waste disposal.

Gene emphasized that whether we view the water impairment from a historic or current perspective, we can’t choose to walk away from this ongoing legacy of degradation. We have to deal with it in an incremental manner, in a meaningful way. It’s not something for someone else to take care of. Furthermore, it’s not enough to simply clean up sites like this. It’s equally imperative that we view it as an opportunity to create a park amenity, a teaching tool, a recreational resource. Our goal should be to create a landscape that inspires.

Read more about the cutting-edge technology used at the LSL in our Spotlight on Science section.

Living Systems Lab

As part of the BRWA’s annual meeting, Gene Bernat, CEO of the Fisherville Redevelopment Company, gave a tour of the biological remediation complex in South Grafton where the Blackstone Canal joins the Blackstone River. The Fisherville Mill site has a long, toxic legacy of soil contamination that includes two leaking underground tanks of heating oil #6— a product that does not respond to standard biological remediation utilizing oxidation. In addition, 55-gal drums of cleaning solvents from various businesses had been dumped in dry wells on site. Denser than water, these solvents had sunk low and affected the local aquifer.

In 1999, a massive fire destroyed the Fisherville Mill. During the fire fighting effort, ten million gallons of water were pumped out of the ground, creating a toxic plume of trichloroethylene (TCE) in the local drinking water supply. While this particular contaminant has been largely remediated, the heating oil and other toxins remain in the soil and surrounding water.

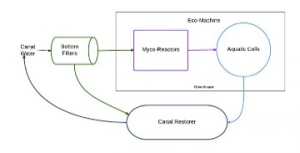

Gene began the tour at the canal, where the first and last stages of a four-part bioremediation process take place. In the first stage, microbial bottom filters treat the canal water as it is drawn into the greenhouse. The second and third stages of treatment occur within the plant racks and water tanks of the greenhouse, as will be explained below.

After it has been processed in the greenhouse, the water is sent to the Canal Restorer, engineered islands of marsh hibiscus and other aquatic plants that perform the final stage of bio-filtration. Gene commented that, when in bloom, the hibiscus is stunning, helping to make the site a destination separate from the bio-remediation processes that are underway and unseen. He also pointed out the beautiful and historic stone arch bridge under which the canal passes. The arch’s sensitivity to vibrations limits the heavy machinery that could otherwise be used on site for remediation.

Leading us into the greenhouse, Gene explained how canal water is shunted into the facility. Racks on one side of the building hold trays of wood pellets that have been inoculated with four cultures of mushrooms: turkey tail, oyster, scaly tooth, and wide caps. They perform both mechanical and biological filtering by breaking down the heating oil. Mushrooms grow by changing their environment, and absorbing sugars through their cell walls. They do this with the same digestive juices that people use to break down food; the difference is that mushrooms do it externally. The mushrooms do not distinguish between the wood pellets and the oil on the wood, so as their enzymes go to work, both food sources are digested.

One of the most fascinating lessons learned in the Fisherville project is the specificity mushrooms have to the various compounds of the heating oil. Just as different species of mushrooms vary in their preference of tree host, each of the four fungi work on different molecules in the petroleum. As Gene explained it, enzymes are a lock and key system with the food as a lock and enzymes as the key. Each key fits a particular lock. It is only through the combination of multiple mushroom species that all the elements of the heating oil can be broken down.

These complex ecological relationships demonstrate the vital importance of conserving biodiversity. There is an immense amount that we still do not know about the role each organism plays in natural ecosystems. Therefore conserving each species, to the extent possible, is critical for future ecosystem function and integrity.

Once the canal water has moved through the racks of mushrooms, it enters a series of six water tanks or “aquatic cells” inside the greenhouse. Each tank contains a floating mat of native aquatic plants with roots descending into the water. Gene tilted one of the plant mats to show the trailing roots. It is here, below the surface, where the real work takes place.

As the water moves through the sequence of aquatic cells, more and more of the contaminants are drawn up by the roots to support plant growth above the surface. It was clearly visible how root length gradually increases as you move from the first to final tank. This reflects the gradual decrease in contaminants (food) for the plants. In Tank 1, the water contains the highest level of compounds and the plants do not have to work hard to secure the nutrients. By the sixth and final tank, most of the compounds have been filtered out of the water, so the plant roots grow longer as they work harder to secure the necessary food to survive and grow.

The tour ended with Gene reiterating his goal to see the Living Systems Lab serve not just as a site cleanup, but also as an opportunity to build community by engaging every one of us in the ecological restoration process. We must put an end to treating the river and other waterways as open sewers (e.g., antibiotics, microbeads). We should all strive to view these as a resource to embrace and maximize, not a liability to put a band-aid on and walk away from. It is Gene’s vision that the Fisherville Living Systems Lab serve as a model that can be replicated up and down the Blackstone River and throughout the watershed to meet the individual needs of each community. That should be the legacy we leave behind.