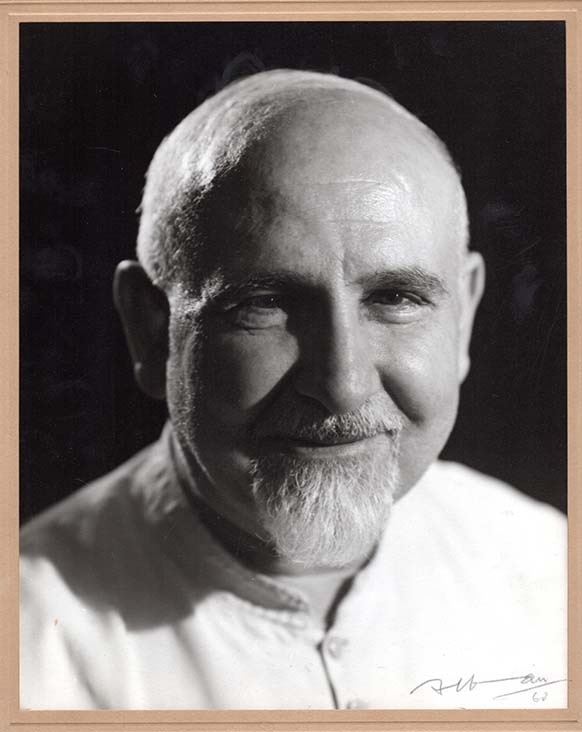

Reverend Father Krikor Guerguerian (12 May 1911-7 May 1988) was born in the district of Gürün, which is in the province of Sivas. He was the youngest of 16 siblings, eight boys and eight girls, only six of whom survived the Deportations. The other ten were killed, along with their parents. Krikor personally witnessed the killing of his parents. Years later Father Guerguerian visited his home town and faced with the perpetrator of his family’s killing. In an interview he tells us about this moment: https://sfi.usc.edu/video/krikor-guergeurian-meeting-perpetrator

Together with one of his older brothers, he succeeded in reaching Beirut in 1916, where he was taken into an orphanage, and it is there that he spent his childhood years. In 1925, he enrolled in the Zımmar (Bzemmar) Catholic Monastery-School, and, after graduating from Beirut’s St. Joseph University in the early 1930s, he went to Rome, to the Levonian Academy, with the intention of continuing his theological education and becoming a monk, an ambition that was fulfilled in 1937, when he earned the right to become a Catholic monk. During the same year, Father Krikor decided to pursue a doctorate on the subject of the Armenian Genocide, but he would never complete it, despite working on it for the rest of his life. Krikor Guerguerian later moved to United States, where he lived in New York until he passed away in 1988.

Reverend Father Krikor Guerguerian

Born, May 12, 1911 – Gurin, Sebastia

Ordained, November 1, 1937 – Rome

Died, May 7, 1988 – New York

The archive is truly the product of his life’s work. Father Krikor’s meeting with a former Ottoman judge would become a turning point in his life, as well as for his archive.

Before the genocide, Krikor’s eldest brother, Bedros, had gone to Cairo and settled there. After he became a monk, Krikor settled there himself. While continuing his research in Cairo, he met Kürt [“Kurdish”] Mustafa Pasha around 1952. The latter, who was also known as Nemrut Mustafa Pasha, had been one of the presiding judges in Istanbul’s First Military Tribunal/Court-Martial (Divan-i Harb-i Örfi) that heard the cases against the Union and Progress officials between 1919 and 1921. While serving in this capacity, Mustafa Pasha had been arrested in October 1920 on the charge of having intentionally forged documents in one of the trials, that of the Bayburt County Executive (kaymakam) Nusret, so as to be able to sentence him to death. Mustafa Pasha was convicted but later pardoned by the Sultan. Fearing that he might be rearrested when Istanbul was captured by the Turkish Nationalist Forces in 1922, he fled to Cairo.

In a brief note, he wrote that he and Mustafa met numerous times and held lengthy discussions and debates. For his part, Mustafa provided important information to the young Guerguerian. According to Mustafa’s account, the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul was an intervenor in the trials of the former Unionist officials and, in this capacity, it had (and exercised) the right to have a copy made of the papers contained in the various case files. When the Turkish Nationalist forces took control of Istanbul, the patriarchate decided to send all of the documents in its possession to Marseilles, France, for safe-keeping. One of the reasons for sending them to Marseilles was the presence there of Father Grigoris Balakian. Later on, these documents would be sent to Manchester, eventually making their way to the final destination, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Krikor Guerguerian would thus make his way to the Jerusalem Armenian Patriarchate. Years later, he would tell his nephew, Dr. Edmund Guerguerian, that “[he] photographed everything [he] saw there.” Even though there are some materials that he could not film, we can confirm that he was telling the truth.

Over the years, the Guerguerian Archive waited, almost untouched, to be used. Even though the Armenian Assembly in Washington had microfilmed the entire archive and made it available for scholars in 1983, not many scholars were aware of these materials’ existence and thus they largely remained unused.