Wednesday, September 7, 2011

From This week in Sociology

Bread and Roses: Dignity and Respect in Working Class Struggles

by Robert J. S. Ross, Clark University, Professor of Sociology

On January 11, 1912 a group of Polish women textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts discovered that their employer had cut their total wages as a consequence of a Massachusetts law which had cut the legal work week from 56 to 54 hours. The next day, January 12, workers in the American Woolen Company Mills also found that their wages had been cut. Prepared for the events by weeks of discussion and debate, they walked out. Upon their exit began an iconic American strike.

Thus states one of the 97,600 websites that Google reports joining the phrases “bread and roses strike” with women. 1.9 million sites join bread and roses with Lawrence.

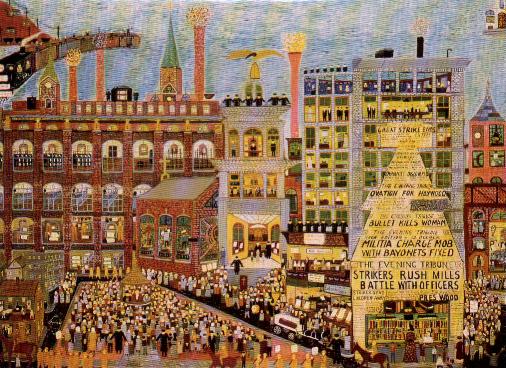

The strike involved about 25,000 workers – almost all of them immigrants and many of them women. Working conditions and life in the mills and neighborhoods of Lawrence were grinding and miserable. From January to March the workers endured repression and hardship. Martial law and militias were arrayed against them, including the use of armed Harvard University students. In the end they won wage and other concessions that would last for a few years, though were not permanent. And eventually most mills left New England and moved to non-union states in the South (1920s and 1930s) before moving again overseas in search of even cheaper labor and fewer environmental and other restrictions.

A poem by the radical writer James Oppenheim is often cited as having been inspired by the Lawrence strike. It includes the lines:

“Our lives shall not be sweated, from birth until life closes; Hearts starve as well as bodies; Give us bread and give us roses.”

And

“Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for — but we fight for roses, too!”

But scholar Jim Zwick has shown that the poem was published in 1911 – before the strike, and was probably inspired by Chicago events.(Zwick 2002, 2003) In 1996 Gerald Sider found that no photo of strikers, their marches or pickets showed the “bread and roses” phrase on a picket sign. No pamphlet in the Lawrence public library files has the phrase. No real time news article reports the phrase being used.

Some of the labor historians confronted with Sider’s work argued that perhaps the phrase was from the Italian radical poet Arturo Giovannitti, a Lawrence strike leader, and that it appeared in Italian. But a young history student showed years ago that Giovannitti never used the phrase “pan e rose” in his published work during or after the strike.

A reasonable conclusion, bearing in mind the difficulty in proving something didn’t happen, is that the slogan does not stem from the strike, but rather is a constructed memory. From the troubadour Utah Phillips through to the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities to many trade union publications, and on tens of thousands of websites, the Roses of the Bread and Roses Strike stand for those dimensions of labor and working class aspirations that embrace needs that are aided but not summarized by the ascent toward material decency.

Through the years sweatshop workers’ complaints are instructive. They complain of abusive language, sexual harassment, and of miserable sanitary facilities.(See inter alia Ross 2004, Chapter One) They complain of being called dogs and being treated like dogs. When workers resist this treatment they almost always articulate the twinning of material demands with claims to dignity and respect. The picket signs carried by the striking sanitation workers in Memphis, in 1968, just before Martin Luther King was killed, said simply “I AM a man”.

The memory of the 1912 strike is constructed of our hopes and aspirations. The historian Ardis Cameron suggests that the idea of the Lawrence strike as a fight for bread and roses is as Harney put it “an example of a “wrong” story which communicates a “right” message.” One definition of a myth is, “a traditional tale with … partial reference to something of collective importance”. (Burkert 1982:23) A view of legend includes “a symbolic representation of folk belief and collective experiences and serving as a reaffirmation of commonly held values of the group to whose tradition it belongs.”(Tangherlini 1990:85)

Our effort today is to reveal just how important dignity and respect are in labor movements and working class struggles. So important, that we construct legendary histories to instruct ourselves and those who come after us.

References

- Burkert, Walter 1982. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. University of California Press.

- Ross, Robert J.S. 2004. Slaves to Fashion: poverty and abuse in the new sweatshops. Ann Arbor. University of Michigan Press.

- Sider, Gerald M. “Cleansing History: Lawrence, Massachusetts, the Strike for Four Loaves of Bread and No Roses, and the Anthropology of Working-class Consciousness,” Radical History Review, No. 65 (1996): 48-83, and comments by Paul Buhle (pp. 84-90), Ardis Cameron (pp. 91-97), David Montgomery (pp. 98-102), and Christine Stansell (pp. 103-107), and a reply to the comments by Sider (pp. 108-117).

- Tangherlini, Timothy. 1990. “‘It Happened Not Too Far from Here…’: A Survey of Legend Theory and Characterization” Western Folklore 49.4:371-390.

- Zwick, Jim. 2002. “Bread and Roses: The Lost Histories of a Slogan and a Poem.” Originally published online at http://www.boondocksnet.com/labor/history/index.html but the site, created by Zwick ended after his death (2008). I have a cached copy and will send it to scholars upon request. Similar material is available in Zwick., 2003.

- Zwick, Jim. 2003. “Behind the Song: Bread and Roses.” Sing Out! 46 (Winter 2003): 92-93.