A new paper was recently accepted at Environment and Planning: A. In it I pick up on an emerging debate over the explosion of city-to-city policy parnterships (C40 Cities, the Cities Alliance, etc): scholars have descibed this phenomenon as an ‘oligarchic diffusion’ of public policy between city elites, as city halls develop their own forms of ‘diplomatic entrepreneurship’, and urban policies become transnationally ‘mobile’ between cities via various consulting/knowledge/political networks. Benjamin Barber’s recent TED talk on ‘why mayors ruled the world’ provides a good — but problematically uncritical — summary of this explosion in globally-focused urban-based governance.

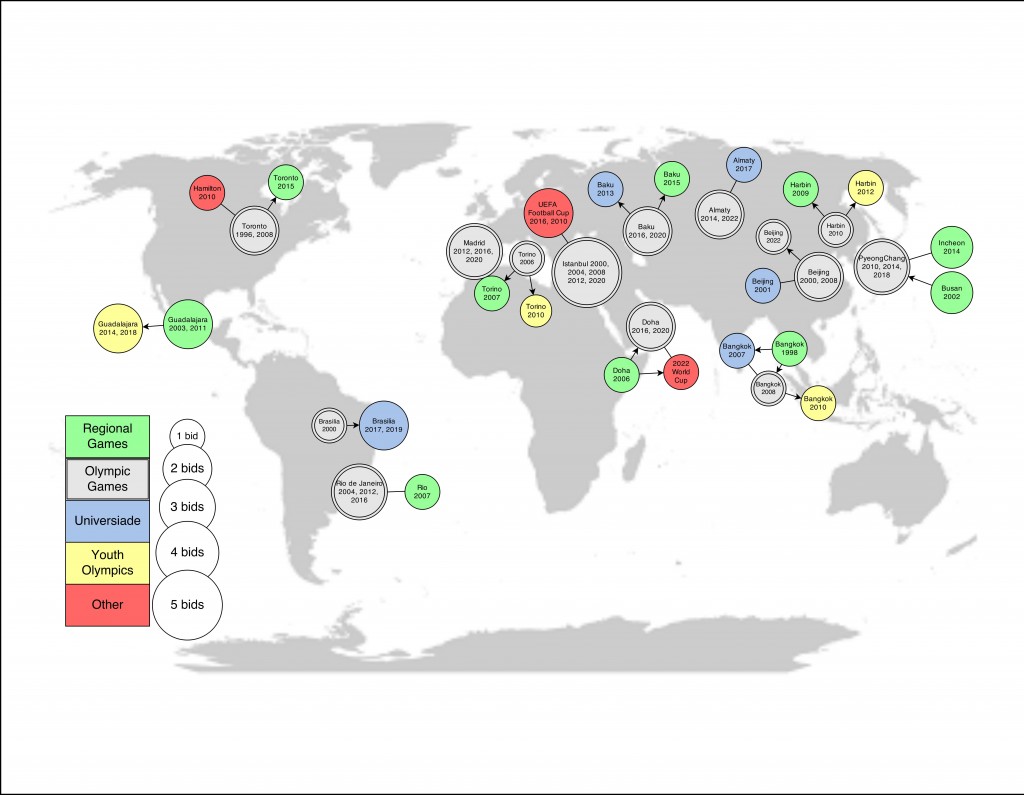

The core argument of this paper is that these various forms of sharing policy between cities need to be reconsidered. They are not simply about sharing and learning, but also about selling and branding: there is a deeper entrepreneurial logic behind cities’ decision to build policy partnerships with other cities. Olympic bid cities are a case in point: they extensively network amongst each other, sharing expertise on everything from consultant lists to technical standards. Yet very little of this ‘sharing’ is altruistic: many cities are instead using transnational knowledge networks as a means to build legitimacy for local projects.

The paper is forthcoming at Environment & Planning A. The final version is available on my Academia.edu page.

Title: Competition through inter-urban policymaking: bidding to host mega-events and entrepreneurial networking

Keywords: entrepreneurial city, networked entrepreneurialism, urban policy, bidding, mega-events

Abstract: Recent scholarship on policy mobility, globally-active municipal governments, and transnational city-to-city policymaking suggest a new dynamic in entrepreneurial cities: entrepreneurialism based not only on place competition, but also based on practices of inter-urban networking. This paper argues that cross-city initiatives to share planning expertise can function both as policymaking networks and as markets for policy knowledge, as urban governance stakeholders strategically leverage inter-city initiatives for sharing urban planning knowledge. Bidding to host sporting ‘megaevents’ highlights these networked entrepreneurial strategies. A comparative study of bids to host the Olympic Games over a twenty year period shows that policymaking knowledge (templates, models, and best practices) shared between cities is both necessary for competing to host events, and represent ‘policy commodities’ that planning coalitions can use as part of their entrepreneurial portfolios. While much commentary on inter-urban policymaking focuses on how policy practices are received by cities or mobilized by international businesses or policymakers, this paper signals to a multi-directional entrepreneurial strategy: although megaevents federations and sponsors developed megaevents knowledge networks to leverage urban planning for profit, many local development coalitions have incorporated these same networks into their competitive strategies.