I recently presented a paper at a conference on Transformative Possibilities in the Global South, a sociology of development conference hosted by Brown University’s Department of Sociology and Watson Institute for International Studies. My paper on Upscaling Development? Urban Governance as Developmental Politics argued that urban is increasingly adopting the practices of ‘developmental states‘. I show a qualitative distinction in how policy stakeholders understand the scalar relationships at play in urban development planning. A rich scholarship has explored how policy is ‘downscaled’ from (inter)national institutions into the city by ‘rescaling the state’ through ‘state spatial strategies’. However, I argue that urban development planning also – and increasingly – involves processes of ‘upscaling’ development policy from urban places for use in other cities, in national debates, or in partnership with international institutions. I use urban enclave planning in Doha, Qatar as an example: Like other peers in the Gulf, the Qatari state’s initiatives are often managed through state-owned real estate ventures. I demonstrate how these state-owned enclaves are used as policymaking ‘laboratories’ for experimenting with urban development (technology and design, policy templates, best practice guidelines, etc).

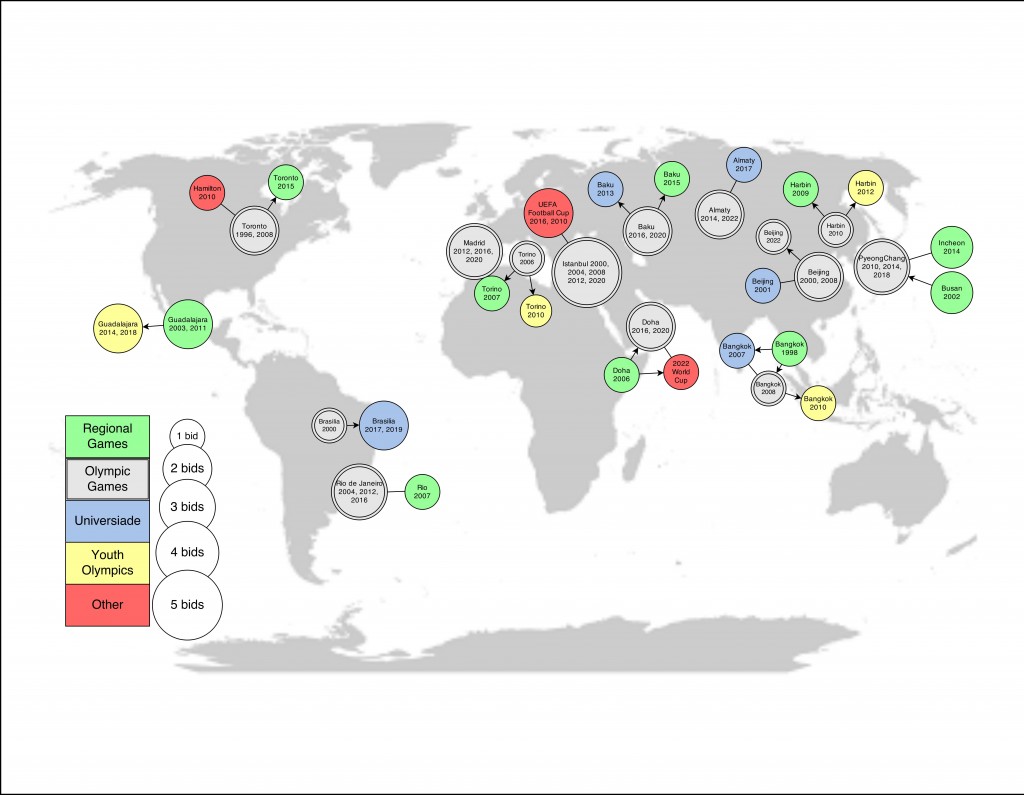

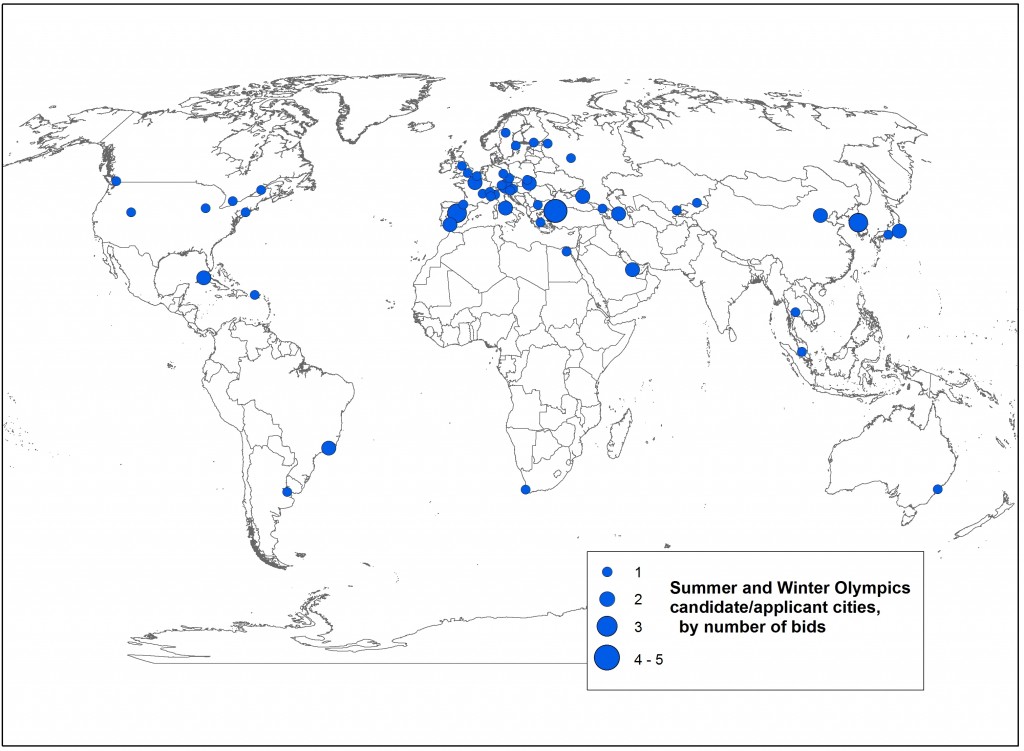

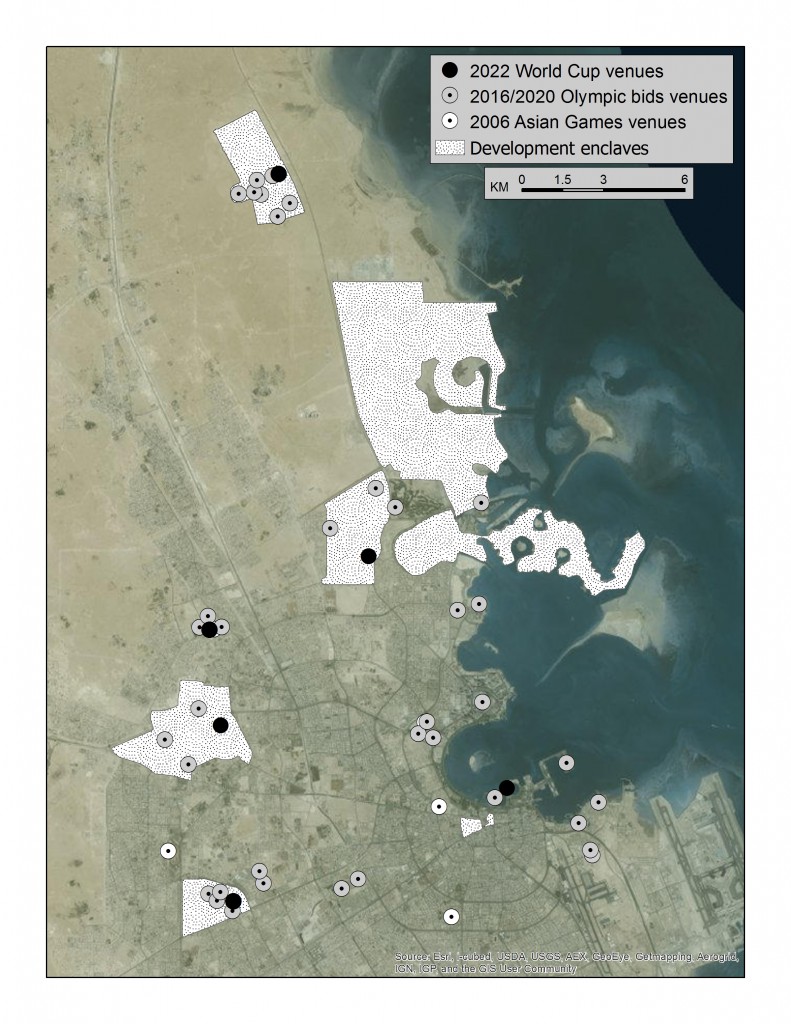

State-owned or parastatal master planned enclave initiatives, compared with mega-event investment plans.

The laboratories aim to export lessons learned in the enclaves to (inter)national policy projects. For example, the former site of the 2006 Asian Games has evolved into a key site for sports science research and elite sport training; institutions based there play a leading role in designing policy and providing training for Qatar’s various ‘sport for development’ foreign aid programs.

The ‘Sport City’ enclave, recently renamed the Aspire Zone, hosted most of the 2006 Asian Games events and now plays a prominent international role in sports science and training.

Please feel free to email me for a copy of the working paper.

Title: Upscaling Development? Urban Governance as Developmental Politics

Abstract: Urban governance is becoming increasingly ‘developmental’, as urban planning practices are viewed as a means for actively defining and intervening in development using state-led models. That is, there has been a shift in the role of ‘the city’ as a space for development intervention and in the role of states as urban developmental agents. This is evidenced by a proliferation of city-to-city policy networks, by partnerships between municipal states and international development institutions, and by increasingly prevalent narratives which signal to the need for global-urban development planning. These shifts signal to increasingly proactive municipal governments which experiment with urban planning tools in order to pursue a diverse set of development agendas, and have prompted debates over the opportunities and challenges of democratic governance in urban state-led development planning. I argue that these shifts also mark a qualitative distinction in how policy stakeholders understand the scalar relationships at play in urban development governance. A rich scholarship has explored how policy is ‘downscaled’ from (inter)national institutions into the city. However, I argue that urban development planning also – and increasingly – involves processes of ‘upscaling’ development policy from the city for use in other cities, in national debates, and in partnership with international institutions. I demonstrate this upscaling with a case study of developmental real estate planning in Doha, Qatar. I demonstrate how the Qatari state’s real estate ventures are used as policymaking laboratories for experimenting with development policy. The laboratories aim to export lessons learned in the enclaves to international policy projects, especially though Qatar’s foreign aid programs. This study contributes to broader debates over the role of urban governance in international development policymaking, and the agency of urban-scale governments in the process.