As six cities begin the early stages of bidding to host the 2022 Winter Olympics, it’s important to keep in mind that most of these bids are not happening in isolation. Cities rarely bid to host a single event; a much more common strategy is to develop a general sports development plan (what types of facilities, where to put them, how to pay for them, etc) and then recycle that plan in pursuit of a variety of sport megaevents.

The international sports megaevents calendar is dominated, unsurprisingly, by the Summer and Winter Olympics. (FIFA World Cups draw a comparable crowd and require similar levels of investment, but this post focuses on events that are hosted by cities…the World Cup is hosted by a national government and thus entails a different set of implications for planning and public policy.) Within the Olympic calendar, there are also a number of smaller ‘major events’. The planning implications of these events are qualitatively comparable to Olympics planning, but occur on a smaller scale: they involve a similar ‘multi-sport’ program that uses Olympic-specification facilities, they are planned on a two or four year cycle, and potential host cities participate in a formal, Olympics-style bid competition to host them. The Youth Olympic Games is one such event, and the Paralympics are another (Paralympics, however, are planned simultaneously with regular Olympics and hosted in the weeks preceding/following the formal Games). Regionally, several continental Olympic associations host smaller events: the Pan-American Sports Organization has the Pan-American Games, the Association of African National Olympic Committees runs the All-Africa Games, the Olympic Council of Asia maintains the Asian Games, and the European Olympic Committees will launch the first European Games in 2015. Moving beyond the Olympic franchises, the Commonwealth Games Federation imitates the Olympic planning system (and uses almost identical templates, benchmarks, and planning lifecycles). The World Student Games bill themselves as “only second to the Olympic Games”, and are another major player on the bidding circuit. These latter two events are functionally similar enough that Olympic bid committees can also compete to host these types of games.

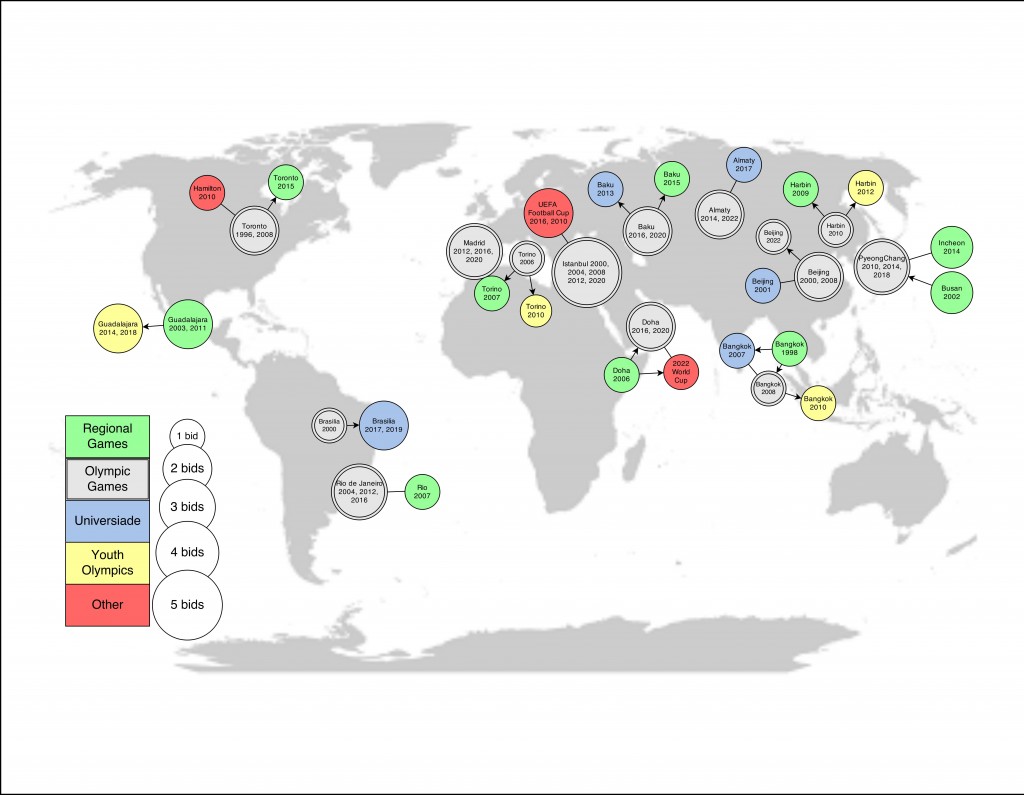

In total, over the past 20 years 114 cities have bid to host one or more of these mega/major events. Many have bid multiple times to host either the same event or to host different events. Within this group of ambitious cities, however, some planning coalitions are particularly ambitious and bid both widely and persistently. These are diagrammed below (a JPG is posted here, and an interactive XML available via request).

Since the early 1990s, 17 cities have been particularly active in bidding on megaevents, placing 56 different bids.

By bidding so prolifically, planning coalitions in these cities are speculating on a large scales: Olympic bids often have budgets of $3-5 million per bid, for instance. While bid committees are often able to recycle large parts of one bid for use in another, high-frequency bidding for megaevents represents a significant commitment of public (and/or public-private partnership) resources. Bidding itself certainly has benefits: even unsuccessful bids generate publicity for government planners and provide a catalyst for redevelopment projects that were in various states of ongoing planning before the bid. There is an ongoing, but hotly contested debate over whether the bid itself can contribute to national economic growth. There is, however, a pressing need to consider the public policy implications of high-frequency bidding. More of my research on the topic is forthcoming…so please feel free to contact me with questions!