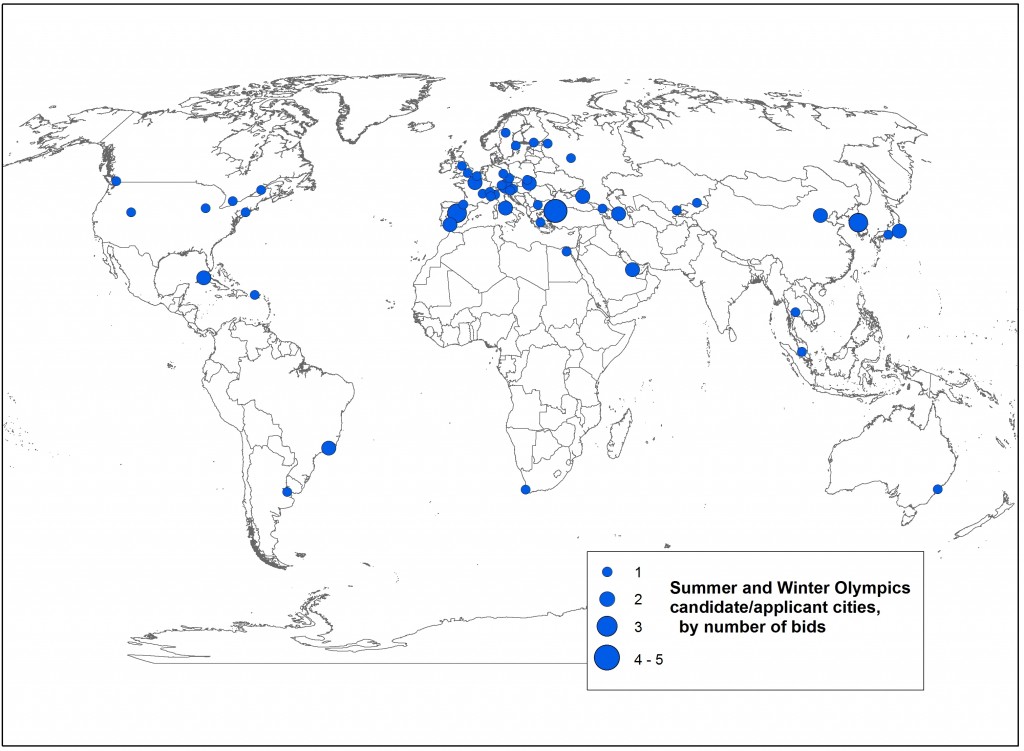

Over the past 20-25 years, bidding to host Olympic Games has become an integral part of global urban policymaking. In fact, committees in 56 cities have prepared bids to host Summer or Winter Games between 2000 and 2020 (the bids date from 1991 to 2013). Likewise, 14 of these cities have bid to host multiple Games, incorporating Olympic bidding into their long-term planning strategies in the process. Bids to host a ‘mega-event’ like an Olympic Games require large amounts of capital; the design and implementation of strategies for fundamentally redeveloping a city’s landscape; and extensive coalition-building across urban, national, and international institutions. Even though only a handful of these cities have been ultimately successful in hosting an Olympic Games, designing a bid to host is a complex, large-scale urban planning project in itself.

Bids to host a Summer or Winter Games, 2000-2020 (bids date from 1991-2013) Assembled from a variety of archival sources; cartography by the author

Likewise, many cities bidding to host Olympics simultaneously pursue other hosting opportunities. The bids for one type of megaevent rely often on the same plans as those proposed in other megaevent bids, and thus even unsuccessful bids to host the Olympics may help with a successful bid to host a Commonwealth Games, significant components of a FIFA World Cup, or various regional sporting events. Some examples of these institutional connections between bids include links between: the Manchester 1996 and 2000 Olympic bids and the Manchester 2002 Commonwealth Games, the Cape Town 2004 Olympic bid and the South Africa 2010 World Cup, the Doha 2016 and 2020 Olympic bids and the Qatar 2022 World Cup, the Rio de Janeiro 2004 and 2012 Olympic bids and the Brazil 2014 World Cup and Rio 2016 Olympics.

This matters because event-planning can distort a city’s long-term planning objectives (or vice versa). Megaevents require highly specialized investments, which may crowd out spending on other forms of infrastructure in a city’s master plan. The International Olympic Committee itself has expressed concerns about this: in a recently published evaluation of the 2020 bid cities (Istanbul, Madrid, and Tokyo), the commission expresses concerns that:

Throughout recent bid processes, the IOC has witnessed a growing tendency by cities to try to go above and beyond IOC requirements. Whilst such offers may appeal to a certain client group or represent “nice to haves”, the future OCOG [Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games] inevitably finds itself facing additional costs to deliver services that have not been requested by the IOC. Throughout the 2020 bid process, the IOC has underlined the efforts it is making to manage the cost, size and complexity of organising the Olympic Games. The Candidate Cities were reminded that IOC requirements are actual requirements and should not be interpreted as minimum requirements. Cities were instructed that should proposals be made which go beyond requirements a clear case would have to be made demonstrating the rationale for this – operational reasons, legacy considerations, etc. (19 April 2013, p 6)

In short, helping cities develop reasonable plans which make sustainable contributions to urban development during the bidding process is a significant concern for all involved. Sustainable bidding is important for successful host cities because planning trajectories will already be ‘locked in’ by the time a city wins a bid. This project can also identify sustainable development practices for unsuccessful candidate cities: bids are themselves complex planning projects that can leave institutional and physical legacies on a city’s urban master plan.