Who is He?

Barnett Newman was born in the early 1900’s and worked steadily as a colorfield painter in the first major avant-garde art movement known as abstract expressionism, a period of postwar art. Newman’s art often investigates the symbols of Jewish mysticism while playing with the use of color and investigating how it changes. His signature device and artistic trademark can be defined as a “zip”, what he defines as a vertical line of color that represents a single ray of light and divine action.

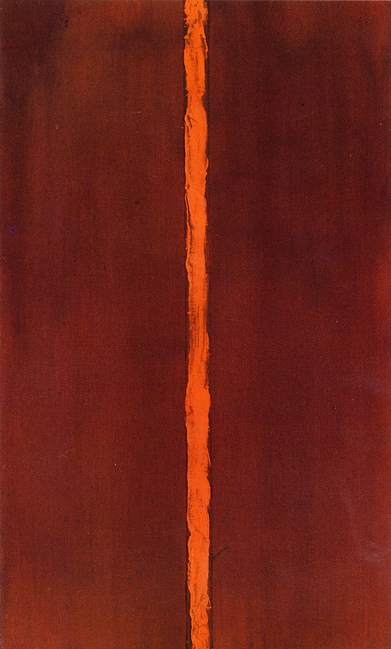

Onement

For Newman, Onement is viewed as a breakthrough that would carry through to much of his later work. This work features the first use of the “zip”, a vertical line of orange that both separates and unites either red side of this piece. The title, Onement, is said to have been influenced by the medieval term which means ’to unite’. Later this term evolved into religious contexts known as “atonement”, interpreted as the act of amends for sin and/or the Atonement of God and man through Jesus. Defining this term makes creates two clear ideas that stem directly Newman’s from intentions and artistic statements. Firstly, Newman expresses that these “zips” do not divide the canvas, but merge outer sides – this reasoning stands as the interpretation for the antiquated term that is “onement”. Additionally, when we interpret the modern use of the word, “atonement”, we can clearly delineate the religious context of Newman’s exploration of Jewish mysticism.

Newman’s canvas seems to be both united and divided by the centered ‘zip’; the compositional arrangement of color and line could be read as a diptych in this particular piece. It is clear that Newman had intended to united the outer sides with the ‘zip’. In like manner, The Garden of Earthly Delights has various compositional readings. Though Bosch’s work was indeed intended to be in a polytych format, the mixed interpretations convey a message similar to that of Newman especially when contemplating concepts of morality and religion.

“I hope that my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality, and at the same time of his connection to others, who are also separate, . . .I think you can only feel others if you have some sense of your own being” (Newman, p. 257-58).

Newman on ‘Onement I’ and Content

The Sublime is Now

Barnett Newman described himself as “an intuitive painter… concerned with the immediate and particular forms of ‘primitive’ art”. In addition to his very prominent role in the art world, Newman was a writer and theorist of the sublime. In The Sublime, by Phillip Shaw, it is evident that chapter six, “The Sublime is Now” , was heavily influenced by the work of Barnett Newman, as Newman’s landmark essay in 1948 was also titled, ‘The Sublime is Now’ with regard to the desire to destroy beauty in modern art in accordance with the Critique of Judgement by Immanuel Kant. This chapter by Shaw is also backed by the philosophical accounts of the postmodern critiques of culture by both Lyotard and Derrida which also hinge on the Kantian sublime.

Lyotard on Newman: The Instant

The intersection of Newman and the postmodern sublime is situated within what Lyotard calls the ‘postmodern condition’. Philip Shaw defines this condition in chapter six ‘The Sublime is Now’ as “the inability of art of reason to bring the vast and the unlimited to account” (Shaw, p. 115). Shaw further explicates this ‘condition’ as affirming nothing beyond its own failure, and yet, searchingly, pushes forward the unattainable representation of ‘the now’. Lyotard examines the work of Newman in his essay ‘Newman: The Instant’ stating that “there is almost nothing to consume [within his work]” (Shaw, p.121). Shaw turns to highlight Newman’s essay ‘The Sublime is Now’ by observing a quotation with intentions to “reassert…man’s natural desire for the exalted, for a concern with our relationship to the absolute emotions” (Shaw, p.121). Although at first glance, the large blocks of simple color presented by Newman are deceptively uncomplicated, after being engulfed by intense massiveness and consumed by vast and vivid colors, the viewer becomes transfixed, overwhelmed, and essentially transformed into a part of the painting itself.

Lyotard interprets Newman’s abstractions in observing that ‘something happens’ though we are unable to decide what that something is. In ‘Newman: The Instant’, Lyotard addresses Newman’s subject matter describing its paradox. He states,

“The paradox is that of performance, or occurrence. Occurrence is the instant which ‘happens’ , which ‘comes’ unexpectedly but which, once it is there, takes its place in the network of what has happened. Any instant can be the beginning, provided that it is grasped in terms of its quod rather than its quid. Without this flash, there would be nothing, or there would be chaos. The flash (like the instant) is always there, and never there. The world never stops beginning. For Newman, creation is not an act performed by someone; it is what happens (this) in the midst of the indeterminate. If, then, there is any ‘subject-matter’, it is immediacy. It happens here and now. What [quid] happens comes later. The beginning is that there is… [quod]; the world, what there is” (Lyotard, p. 82).

Newman wrote in his essay ‘The Sublime is Now’, “The concern with space bores me. I insist on my experiences of sensations in time – not the sense of time, but the physical sensation of time” (Newman, p. 175). According to Simon Malpas, “The sublimity of Newman’s paintings consists, therefore, in the perception of an instant in which something happens to which we are called to respond without knowing in advance… [how] to respond” (Shaw, p.123). This distinction is important when facing a potential sublime event. If we, the viewers, decide what is happening in a work such as Onement, we aid the the object with a concept and interrupt the possibilities of creating a sublime event. However, by declaring ‘that something happens’ while remaining open to what that ‘something’ may be, we can perceive Onement, as Malpas explains, ‘in the perception of an instant’. This notion of ‘perception in an instant’ radiates Lyotard’s description of postmodernism as an event – the emergence of the ‘now’, a clear theme in Onement by Newman.

Vir Heroicus Sublimis

Vir Heroicus Sublimis hangs at the MOMA in New York City. The title, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, translates to “man heroic and sublime”.