Mark Davidson and I recently published a paper in Antipode: “Negotiating particularity in Neoliberalism Studies: tracing development strategies across neoliberal urban governance projects”. The journal has a paywall, so please email me for a copy if interested.

The Antipode Foundation also asked us to explain the paper in the following video abstract. This article is highly theoretical, though various empirical papers explaining our argument are forthcoming. The article tackles an vexing problem: The 2007-2008 global financial crisis also pushed neoliberal models of city management into intellectual crisis, as core arguments of the neoliberal political project (privatization of public goods, deregulation, and austerity policy) became increasingly difficult to justify. Critics of neoliberalism were subsequently flummoxed: neoliberal ideologies were empirically debunked, but remained deeply entrenched in Global North political systems (e.g. the evidence made clear that the combination of spending cuts and tax subsidies to the wealthy do not produce trickle-down growth, but austerity politics nonetheless became even more prominent after the crisis). These scholars began to speak about neoliberalism as entering a ‘dead but dominant’ phase, as ‘zombie’ economic policy in which the policies were still in place but had lost their ideological/intellectual staying power. Subsequent debates have continued parsing this dynamic, and it is here where our paper enters the fray.

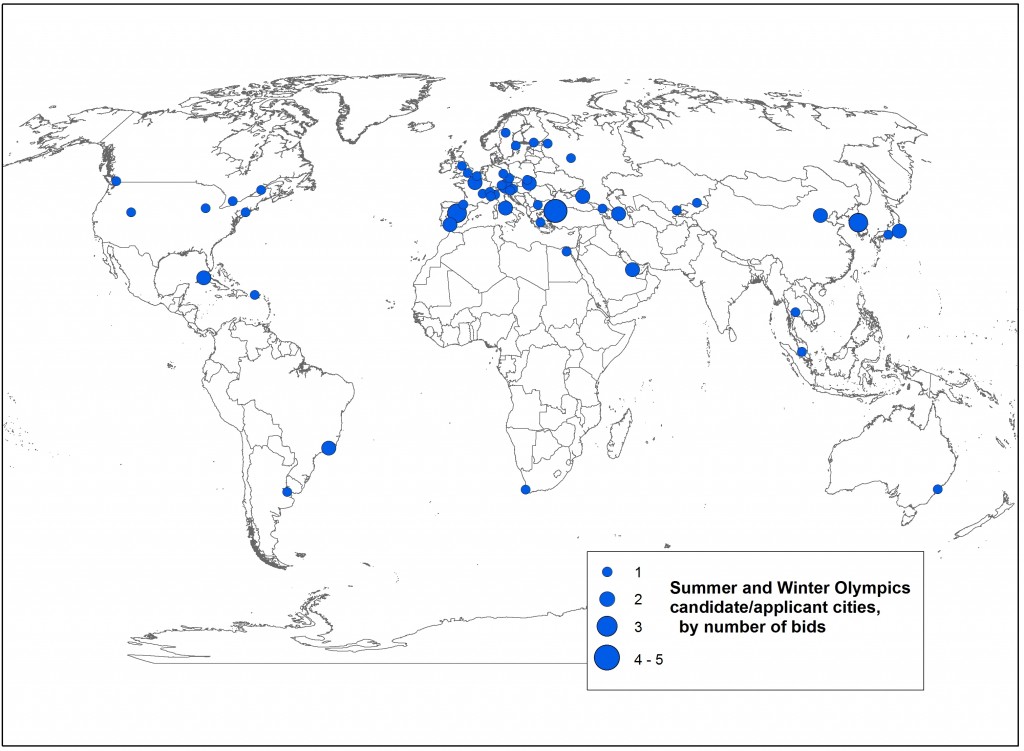

Our argument, briefly, is that to understand this breakdown, we need to trace out the links/divergences between individual neoliberal policy projects and broader intellectual/ideological projects. In the case of megaevents, this means mapping the dialectical relationships between individual/local megaevents planning projects and the transnational institutions/ideas about event-led development strategies. While this lays our a theoretical framework for doing so, forthcoming papers will trace this empirically (please feel free to email me for working papers).

The full post is available at the Antipode Foundation website, the video is also embedded below:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JQocPXoWVY