In my last post, about my research on the Perkins family, I promised to reveal what I believe is the link between Camden and Worcester–the connection that brought about the migration not only of the Perkinses but also likely influenced other Camdenites, such as the Brevard,, Rhodes, Carlos, and Boykin families, to come to Worcester in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like the migration links between New Bern and Worcester (see my book, First Fruits of Freedom), the Camden-Worcester connection was also forged in the Civil War. In this case, the initial connection between South Carolina and Worcester came about through the personal relationship between a sympathetic white minister and two freedpeople, Mary and Jacob Stroyer

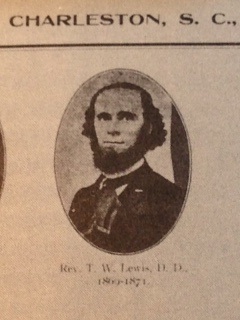

In 1862, the Rev. T. Willard Lewis, pastor of Worcester’s Laurel Street Methodist Church, departed for Beaufort, South Carolina, as a missionary to newly liberated African Americans. (Some sources claim he was the first Northern missionary among black Carolinians.) When Charleston fell to Union forces in 1865, Lewis moved to that city to organize black Methodists under the auspices of the Methodist Episcopal Church, North. As early as 1867, Mary Stroyer, Celia Perkins’ sister (see previous post), worked for Lewis as a cook and laundress. That year, she opened an account at the Freedmen’s Bank in Charleston. Her application notes her employment with the Rev. Lewis, who signed her application and to whom she gave the right to deposit and withdraw money from her account. Mary’s application also lists her birthplace as Camden; Celia Perkins and Kitty Hudson as her sisters; June McCray as her father (with the designation “sold away”) and Pleasant as her mother.

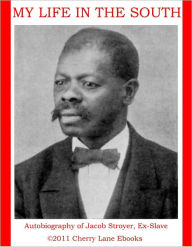

By the time Mary worked for the Rev. Willard, she was married to Jacob Stroyer. Jacob had been a slave of Col. M.R. Singleton, and raised on his large plantation 28 miles southeast of Columbia, South Carolina. In 1879, Stroyer published a narrative of his life as a slave, My Life in the South, that historians have cited extensively. [You can read it at http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/stroyer85/stroyer85.html. For more on Stroyer and the other Worcester Slave Narratives, see McCarthy and Doughton, From Bondage to Freedom: The Worcester Slave Narratives (2007).]

Mary and Jacob Stroyer built a close and trusting relationship with the Rev. Willard. The minister seems to have been especially impressed with the couple and likely used his Worcester connections to help further Jacob’s education. In 1870, Jacob arrived in Worcester and after attending evening classes for several years enrolled at Worcester Academy where he completed a two-year course in 1874. (McCarthy and Doughton, From Bondage to Freedom, pp. 176-77). Mary probably arrived in Worcester sometime in this period.

According to the 1880 census, Mary and Jacob Stroyer lived at 3 Lilly Street. Jacob listed his occupation as “book agent” and Mary worked as a domestic servant. But by that time, Jacob had been ordained a minister and founded and pastored the Colored Mission in Salem. Moreover, in 1878, Mary commenced legal proceedings against Jacob, accusing him of desertion. Jacob continued to be listed in the Worcester City Directory until 1881 and by 1883 Mary had a separate listing.

In 1880, Mary purchased a house at 3 Bath Street in Worcester. Edward and Celia Perkins lived with Mary in 1882 and then moved nearby, living at 36 Abbott and 1 Winfield Street. Mary was active in the AME Zion Church and Good Samaritan Lodge until her death, at age 35, in 1888. In her will she left the Bath Street property to her sisters, Celia Perkins and Kitty Hudson. Celia appears to have purchased Kitty’s half of the property and she and Edward lived there until their deaths in the 1920s. The Bath Street property remained in the Perkins family for approximately twenty more years. The family had photographer Bullard photograph the house around 1900 and the property served as backdrop for numerous Perkins photos in the Bullard collection.

As for the Rev. Lewis, the minister died of yellow fever in 1871 in Charleston, still ministering among the freedpeople. His tombstone on Sullivan’s Island describes him as “The Freedman’s Champion, Counselor, and Friend.” Little did he know that his support of one couple–Mary and Jacob Stroyer– would help pave a path to Worcester for many South Carolina families seeking opportunities unavailable to them in the South.