The Remarkable Story of Stephen Bates

On October 3, 2021, the state of Vermont and the town of Vergennes honored Stephen Bates with a historic marker dedicated to the state’s earliest known Black sheriff. Born enslaved in 1842 on the Shirley Plantation in Virginia, Bates escaped to the Union Army in August 1862 as McClellan withdrew his troops in the Peninisula Campaign. Bates made his way to Washington, DC, where Vermont Congressman Frederick E. Woodbridge hired him as a coachman. When Woodbridge left Congress in 1869, Bates accompanied him back to Vergennes. In 1879, Bates was elected Sheriff, an office he held for all but six of the next 29 years, until his death in 1907. He also often served as the appointed Chief of Police of Vergennes. Bates appeared in newspaper accounts as the arresting officer in numerous cases that included murder, check forgery, and grand larceny. His obituary described him as “almost an entirely self-taught man,” known for his “cool and self-restraint, rarely if ever acting hastily.”

(for more information on Stephen Bates’s life, see https://vermonthistory.org/catalog?folder=56d15100-b0bc-11ea-8b9c-2d3a225c104e)

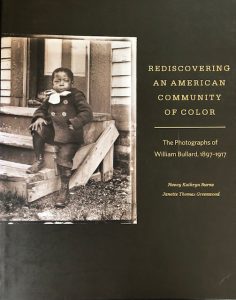

The Bullard Connection

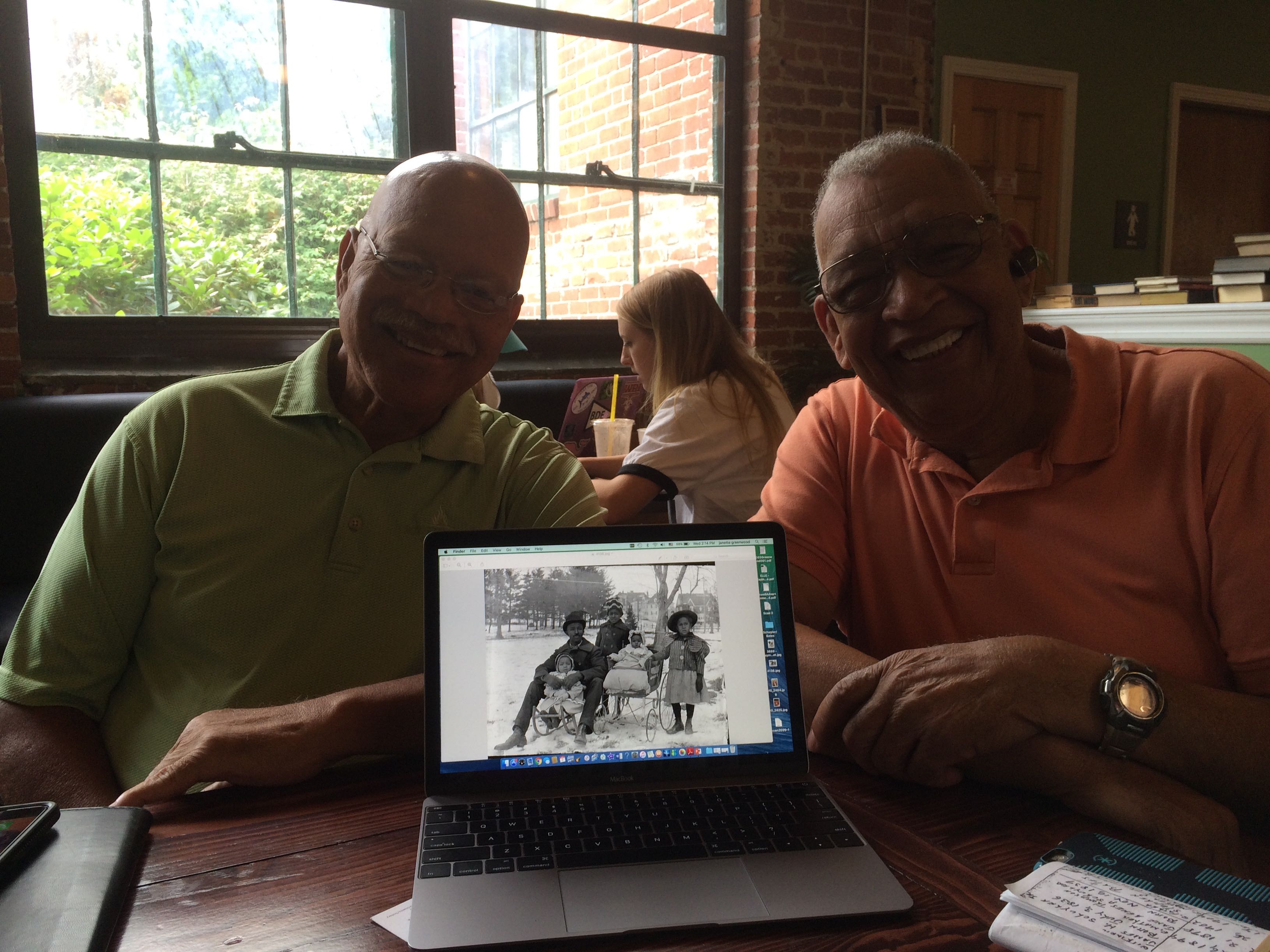

The spark for research that led to the rediscovery of Stephen Bates resulted from a meeting with brothers Larry and Nick Schuyler in September 2016 as we researched the Bullard portraits in preparation for the upcoming exhibition. While sharing this beautiful portrait with them of their grandfather, Raymond Schuyler, and four of his children and learning more about this family from Nick and Larry, I mentioned that in my research I had come across information regarding Stephen Bates as Sheriff in Vergennes beginning in 1879. Bates was the grandfather of these children and the father-in-law of Raymond. (Raymond was married to Rose Bates, the daughter of Stephen Bates.)

I passed along several newspaper articles to the brothers about their great-grandfather’s career as sheriff. This information lit a fire in Larry and jogged his memory: as a young man he had heard family elders talk about Sheriff Bates.

In pursuit of more information, he and his wife, Lynn, made their way to Vergennes in August 2019. Not only did Larry discover more about Stephen Bates in the archives of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where the Bates’s were members, but he and Lynn also found themselves embraced by dedicated community members intent on telling Bates’s story.

A team effort

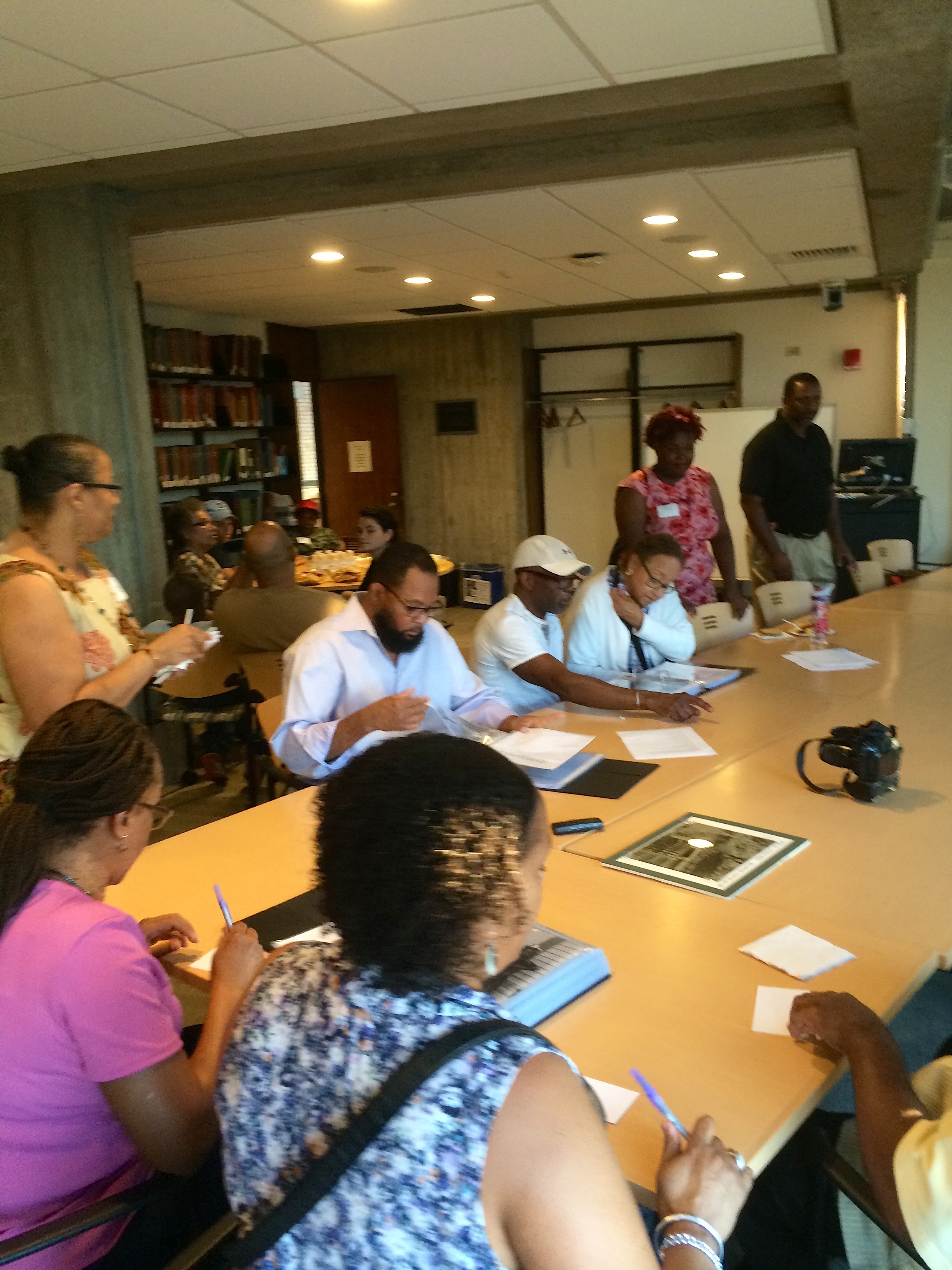

Along with Larry, Bo Price of St. Paul’s Church began researching Stephen Bates and wrote an extensive article documenting his life for the St Paul’s blog. Soon after George Floyd’s murder and as Black Lives Matter protests erupted around the country, Brian Peete was appointed as Chief of Police in Montpelier. News sources stated that he was the state’s first Black police chief. But Bo knew otherwise. She and a team of Vergennes community members, committed themselves to telling the story of Stephen Bates. The team included local historians, Voices in the Parks members, librarians, educators, and others intent on incorporating Bates’s story into local, state, and national history. Digging deeply, they soon referred to Bates’s story not as a discovery but as a “rediscovery.” Their research revealed that his career and contributions had been acknowledged as late as the 1930s and had even been taught in local schools.

To guarantee that Bates’s story would not be lost again, the team applied for a historic marker, which was quickly approved in the summer of 2021. The unveiling of the marker on October 3, 2021, is a testament to an extraordinary life. But it also attests to the power of a dedicated team of community members intent on telling a more inclusive story– not only of their town but of the nation. As Larry Schuyler says of his great-grandfather’s life, “It’s an American story, emphasis on American.”