Invasion Ecology

Invasion Ecology: the impact of Aedes albopictus on native or resident mosquito populations

As Aedes albopictus occupies more and more habitat in the United States, it has potential impact on native container breeding species, such as the treehole mosquito Ochlerotatus triseriatus and the introduced Aedes aegypti in the gulf coast region and peninsular Florida. The impact of this invasion on Aedes aegypti was rapid and drastic– so sudden that there was no opportunity to study it carefully. We hoped that an analogous situation in Bermuda might enable us to look at the albopictus-aegypti interaction in more detail.

North America

in 1993, graduate student Mark Berman and I performed a sampling survey along the east coast of Florida, collecting mosquito larvae in discarded tires (among other container habitats) from the center of each county. Along with the records obtained by mosquito control workers throughout Florida, we were able to see that Aedes aegypti abundance declined in relation to the time since Ae. albopictus had first been reportede. Data for six counties in which Ae. albopictus was reported are shown below, ranging from 7 years (Duval Co.) to 0 years (Broward Co.) are shown below, for urban and rural sampling locations near the center of each county (Bergman and Livdahl, Unpublished).

This result was not unique; similar findings were reported of the takeover of areas, by albopictus, previously dominated by aegypti, throughout Florida and the gulf region.

These data also supported the hypothesis that Ae. albopictus was fluctuating about an equilibrium density in the most established populations in the northern counties. No significant differences were found among the densities at rural sites in counties colonized during or before 1990. In urban sites, Ae. albopictus appeared to have taken longer to reach an equilibrium density; no significant differences were found for counties colonized during or before 1988 (Duval and Alachua).

Bermuda and the Gulf Coast region

Aedes aegypti occupied Bermuda during the slave trade, and thrived in cisterns under houses for centuries, until an intensive control effort eliminated this species in 1960. At least, it was not seen on the island until its reappearance (reintroduction?) in 1998. Concerns over the potential resurgence of aegypt prompted the Bermuda Health Department to establish an island-wide network of egg traps for surveillance and targeted control measures. Shortly thereafter, in 2002, Aedes albopictus was found.

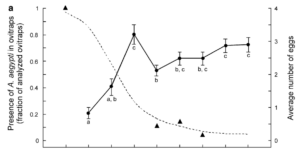

The existence and continued monitoring of egg traps by Bermuda Health Department staff, combined with the identification of eggs by graduate students at Clark (Laran Kaplan and Camilo Khatchikian), provides the unusual opportunity to trace the progress of the albopictus invasion with considerable detail. A spatial and temporal analysis of this invasion revealed that the establishment of A. albopictus occurred simultaneously with the disappearance of A. aegypti. Based on the speed of extinction for A. aegypti, we suspected factors in addition to resource competition, and began to explore alternative mechanisms.

A group at the University of Florida led by Phil Lounibos was also exploring alternatives to competition, including a form of reproductive interference, termed styrization, in which males of one species mate with females of the other, resulting in infertile eggs produced by the female. In this particular case, albopictus was found to have a permanent sterilizing effect on female aegypti (Tripet et al. 2011), and this effect may account for much of the success of albopictus and the decline of aegypti in both Bermuda and the gulf coast region. The same has not been seen in South America, which has been colonized by a tropical strain of albopictus rather than the temperate strain that arrived in North America and Bermuda from Japan (Kotsakiozi et al. 2017). That group has also shown that aegypti has responded to this reproductive interference by evolving resistance to matings by albopictus males (Bargielowski et al. 2013).

References

Bargielowski, IE, LP Lounibos, MC Carrasquilla. 2013. Evolution of resistance to satyrization through reproductive character displacement in populations of invasive dengue vectors. PNAS 110 :2888-2892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121959911

Birungi, J and LE Muntermann. 2002. Genetic structure of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) populations based on mitochondrial ND5 sequences: evidence for an independent invasion into Brazil and United States. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 95(1): 125-132.

Kaplan, L., Kendell, D., Robertson, D., Livdahl, T. and C. Khatchikian. 2010. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Bermuda: extinction, invasion, invasion and extinction. Biological Invasions 12:3277-3288.

Kotsakiozi, P, JB Richardson, V Pichler, G Favia, AJ Martins, S Urbanelli, PA Armbruster, A Caccone. 2017. Population genomics of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus: insights into the recent worldwide invasion. Ecol. Evol. 24:10143-10157. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3514.

Tripet, F et al., Competitive reduction by satyrization? Evidence for interspecific mating in nature and asymmetric reproductive competition between invasive mosquito vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85, 265–270 (2011).