My Identity:

I am a first generation, Latino immigrant from the small country of El Salvador. My own family lived through the 1970s civil war, immigrating to Worcester Massachusetts in 2002 and founds jobs within factories, to make ends meet for me and brother. The highest hourly wage my mom ever made remains less than today’s minimum wage even though her last job was only 2 years ago. Throughout my life, one of my mother’s biggest dreams was ensure me and my brother becoming U.S. Citizens. This meant I went through the process of being classified as an undocumented immigrant to becoming a US citizen in 2019, an intense process that many of my current and future students will need to face as well. Though the similarities do not end there, having spent over 22 years exclusively to the Main South neighborhood, there are many shared experiences between me and my students, witnessing the evolution of the community, both in its growth and struggles.

The Main South Community:

The Worcester Public School district is classified as a title 1, low-income, district. The community itself is comprised of many diverse cultures, experiences, and people as it holds regular festivals to celebrate it. However, it is still ultimately a marginalized community that struggles with violences, drugs, and homelessness that when I was in high school, some of my peers were facing their own struggles of homelessness. As I progress through my career, I will end up far exceeding the household income I had while growing up, but my own upbringing will be one I’ll carry with me as a part of my identity and as a form of trauma. Citing Yvette Jackson, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, “the experiences of African Americans and Latinos living in poverty is no different than the experience of those living through the great depression or major military conflicts.” and these struggles leave behind residue of trauma at an unproportionate rates, to the point that “as many as one-third of children living in our country’s urban neighborhoods have PTSD- nearly twice the rate reported for troops returning from war zones in Iraq.” And when these urban neighborhoods are composed primarily of minorities, the story becomes telling. Unfortunately, this is the reality that me and my students will or have both lived through.

And my role as a teacher:

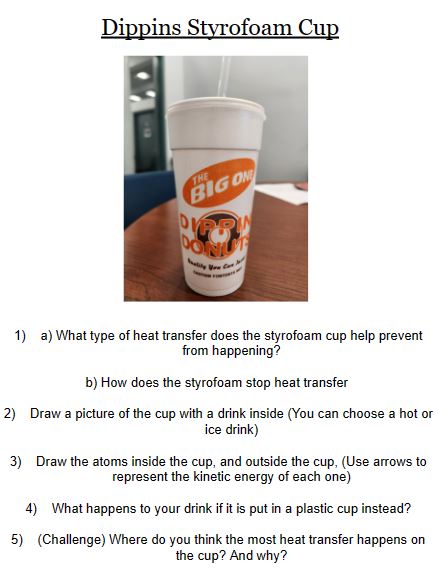

Thinking back to my own experiences as a student in high school, the lessons themselves, classes, or even AP credit would not be what I considered to have been the most valuable aspect of regularly attending school. The main value came in the many different hats that the teachers and administrators wore. For my family, they supported and helped us during the process of receiving our initial residency status. For myself, it was through having a source of consistency in life, being encouraged and supported through my passions of science. There were many more hats that my teachers wore that helped, and now it is my chance to provide those kinds of support as someone teaching in the same neighborhood I grew up in. Looking towards Christopher Emdin’s, who have educators walk the neighborhoods they teach in, learning how to embrace those shared experiences will only act as a strength, even if it’s as simple as creating a problem using the student’s favorite coffee shop. During one of my lessons, my identity and role as a teacher was brought up, where instead of using “standard” phrasing such as “super easy”, or “simple”, to describe a situation where gravity is doing work on a textbook to assist us in dropping it, I had stated that it was “mad easy.” The students had a whole discussion over these two words, with one student saying, “I’ve never heard a teacher say something is mad easy”, showing the common linguistical disconnect between teachers and students.

I decided to highlight my own background to create a sense of unity, to say that I shared similar experiences. I was then hit with the question. “Why do you want to stay here?”, with a tone of confusion as to why I am not trying to “escape the hood.” In that moment a section from Emdin’s book, for white folks who teach in the hood, surfaced in my mind, where there seems to be a general drive to “escape the hood” as if it was a path of gaining self-freedom, this is a phrase that I’ve heard my own student reiterate. Emdin instead argued that instead of dreaming to escape the hood, one should aim to improve it for the next generation. With this as my framework, I simply answered to my student, “to try and make it better”. And so, now as a teacher, I know that my role will lie beyond any notes, labs, or worksheets that I give, my role will become one of finding ways to give to the community, supporting it, and being part of a larger network of foundational support that the schools provide.

Remaining on Christopher Emdin’s teaching philosophy, he does name his book “the rest of yall too” as a way of reaching out to non-white teachers, reminding them that it is still possible to carry with them the harm that happens when white teachers do not provide appropriate culturally responsive teaching methods. That was also something I had needed to think about.