My growth throughout this school year has felt like an up-and-down experience, but one that definitely trended upward greatly as time progressed. From the beginning of the year, I was still trying to find my footing and figure out what worked and what didn’t. One of the first days I had to cover for the geometry classes, the students were given a worksheet that put trigonometry questions into contexts that were intended for them to struggle productively with as they worked through their problem-solving skills. I hadn’t quite been familiar with the idea of productive struggle yet and felt that if the students weren’t getting it immediately, then something wasn’t working. I switched things up and gave them a super simplified plain worksheet that had no real problem-solving skills come into play, which I look back on and wince.

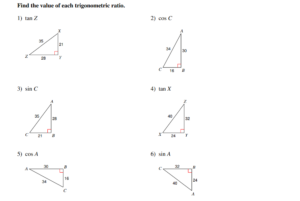

An example of a worksheet I used early on in my teaching year. Not a lot of space for students to do deeper thinking, nor a lot of guidance or scaffolding for students that may struggle getting into the work. Just simple practice.

Early in my takeover for geometry, a lot of my lessons were fairly light on the academic rigor. I hadn’t yet figured out how to properly provide a good challenge for my students that will push them to think critically while also being approachable to them. When my students would finish work, I typically wouldn’t have enough extensions for them to push their learning.

In the same way, I didn’t have enough scaffolds for the students that would need them. Figuring out what worked and didn’t work for my students was a challenge that took a lot of time to learn for me. I believe strongly in making learning approachable for all students and removing any and all barriers possible, but I struggled to make that happen. I would provide students one set worksheet and expect them to figure it out as they went, which left a few students feeling very lost and unsupported.

As time went on, I slowly worked on all three of these ideas. I found myself providing more challenges for students, pushing them to think more critically and work harder in the classroom. When students finished early, I often had more work available for them that pushed their learning and provided them a new challenge. I started creating worksheets that worked more in line with providing a challenge that students couldn’t blow through in 10 minutes, while providing necessary scaffolds and organizations that make it approachable for students.

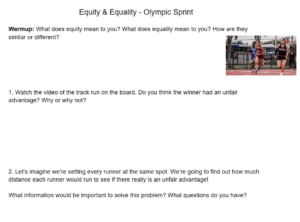

I found myself shifting in how I was approaching teaching, moving away from knowing how to solve a problem to focusing more on knowing how to approach a problem. Problem-solving skills are crucial in a math classroom and our everyday lives. It’s essential that I set students up with the ability to successfully solve problems through trying things out that make logical sense. This was where understanding productive struggle was huge for me. I started phrasing problems as a sort of puzzle for students. I would provide them one problem with minimal information and ask them to write down the information they know, they information they need, how they might go about solving it, and any questions they have. By putting the focus on understanding the problem and how to solve it, students were working on their problem-solving skills and logical thinking simultaneously with the content. Following problems like those, when the students were provided homework or practice, they would generally have a much stronger grasp on the material and feel much more confident in their answers.

A more recent worksheet of a lesson I ran which looked at the mathematics of a running track to determine whether or not lane 8 starting further ahead in the 400m sprint was fair. The sheet asked for students to ask questions and make predictions before tackling the actual math, getting them to think critically.

Through my growth, I also learned how to adapt the content and problems to more fun, real-world contexts. Putting the math in these contexts increased engagement from the students, which got more of them involved in the actual learning. As Kyle Pahigian always told me, engagement is the best classroom management. The students were buying in more to the content the more I was able to apply my lessons to real-world contexts that the students connected with. Classes were filled with discussions about the problems and how the math applies, and through this, students were building problem-solving skills.

My growth wasn’t a linear progression the whole year, however (pun fully intended). Some lessons were better than others, and the reflecting and adjustments didn’t stop after one lesson worked. I fell into a few dips at times in giving straight-forward worksheets and taking the thinking away from the students. However, when these started happening, I would pull myself back, reflect on how I can improve things going forward, and adjust accordingly to bounce back. Some of my biggest steps in growth came from big setbacks, but as Kate Sheppard would tell me after each rough day, it’s not about the fall, but rather the comeback. While I certainly didn’t feel hopeful after bad lesson, I would always try to push myself even harder to get my bearings back and think about how I can come back stronger than before.