I like to think of myself as a teacher and student. I am, just as my students are, constantly learning how to be better at what I do.

I arrived to Claremont completely unaware of what a “heterogeneous classroom” would look like. During our summer institute classes, I kept hearing about all the different levels of students and their capabilities. I learned about Individualized Education Programs, 504 Plans, English Language Learner support, and other important facets of what I was about to experience in my new role.

To give an idea of how heterogeneous my classes were…in the 9th grade group I had 20 students; 14 were ELLs, 4 had an IEP, and 2 had a 504 plan; students came from Worcester, Vietnam, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, and Mexico. In the 11th grade group I had 20 students; about the same number were ELLs, 2 had an IEP, and 1 had a 504 plan; my juniors came from similar countries.

When I began teaching my freshman group, which was my first ever opportunity to be at the helm of a classroom (Pete gave me teaching responsibilities after the second week, much earlier than is typical in the M.A.T. program), I felt overwhelmed for the first couple weeks. I often just handed out the same work to everybody and graded homework using the same standards for all students.

I recall my first two weeks of teaching being very rich with learning opportunities. My second week’s second lesson on the novella “Herman and Alice” was a bit sparse and did not yet show my thinking about heterogeneous learning in the heterogeneous classroom:

But I evolved with my students. I got to know them in and out of the classroom, by talking with them about sports, by attending school events, and by closely reading IEPs and talking with school support staff. I feel that my lessons developed to better address the unique needs of my classroom. Here is a late unit lesson (this one took two days) from Of Mice and Men, which I feel better shows my thinking of all students:

As the year went by with the freshmen, I grew to learn that differentiation was as important for me as it was for my students. I better scaffolded my curriculum. For example, I used different rubrics for my students on IEPs. I built in low-stakes writing for the whole class before beginning bigger assignments; in fact, one of the biggest lessons I learned was that my efforts to assist students on IEPs could be applied to all students.

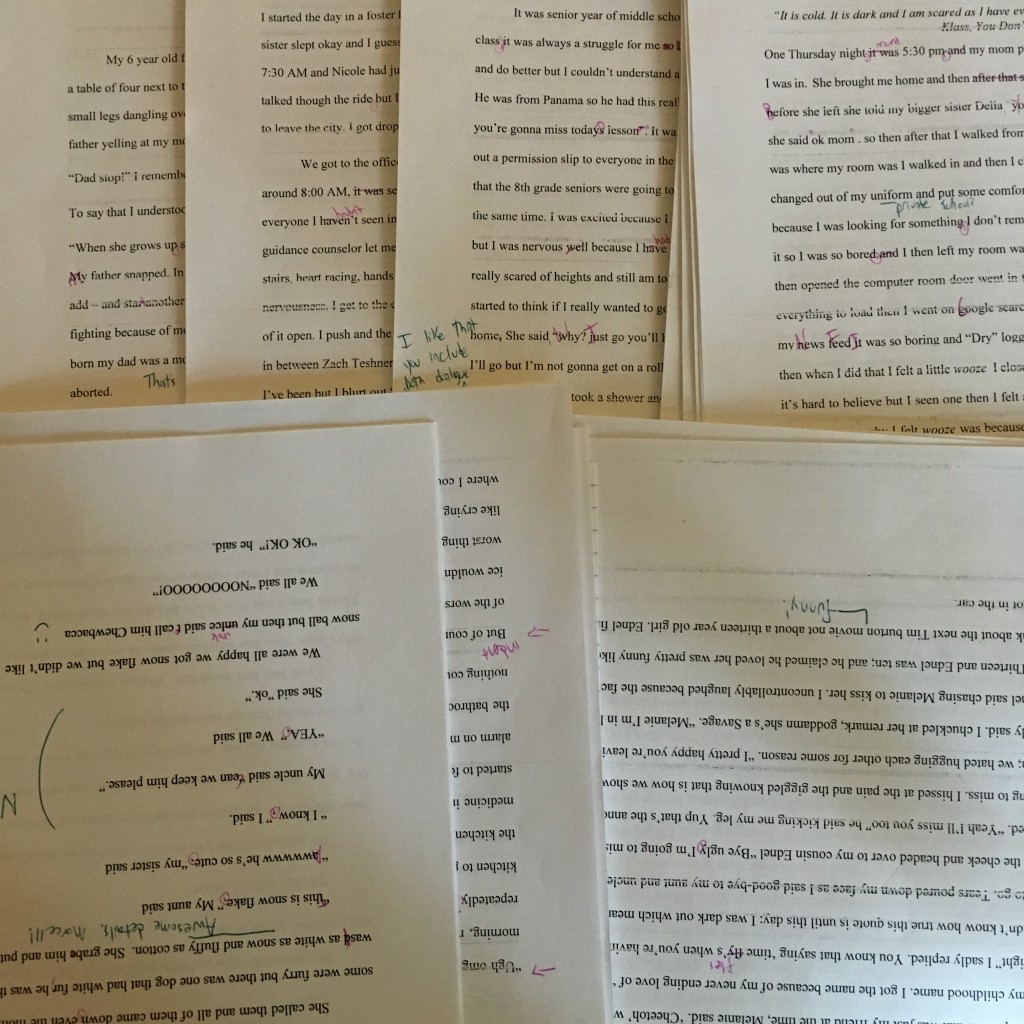

For example, my freshmen were tasked with writing several memoir chapters throughout the year. The first, in October, was a mixed bag (check some of them out on Let Us See). Many students did not include dialogue, imagery, or more than one scene. When I taught some memoir lessons in February, I included guided scene writing where students could flesh out their ideas. I found that students included more dialogue and imagery when we workshopped these things. Additionally, better peer revising and more structured computer lab time lead to increased participation in class.

I also transferred my learning to my juniors when I began teaching them in December. I better brought all the initial learning I had done into that room, while I also explored student interests and strengths in that room. One more LAP, this time from discussion of The Kite Runner.

With the juniors, I had to adapt more quickly, since the material was more complex. I noticed in the first two weeks teaching the juniors that they seemed more reserved. For one, fewer students spoke in class. I started off with lessons that aimed to ask deep questions, giving a lot of effort to posing questions and giving wait time in class. I adapted, though, to the group. After those two weeks, I began coming up with activities that asked students to work in small groups first, and then share out their work. One day while reviewing an important chapter in Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, I gave students assigned groups of 3 students apiece, and I gave each group 2 discussion questions–different for each group. The students were tasked with discussing the questions in groups and reporting the answers out to the class. After, each group had a “first responder” group who had to talk about an agreement or disagreement with what they heard. The activity went phenomenally; all the groups were engaging with each other, and in several cases tertiary groups responded to the others.

“I had a good week with the juniors. […] I have been working more consciously to challenge students through deep conversation and insightful commentary. The way we reached this Thursday was with a layered discussion. I broke students up into heterogeneous groups of 3-4 students each. Then, I let each group pick from a hat, at random, two discussion questions. The pile had ten completely different questions, so that each group could have 2 for themselves. Students had some time to formulate responses and talk, writing their main ideas down to give me at the end. When time was up, groups shared out a response to one question each. Then the group to their left became a first responder and had to offer agreement, disagreement, or a new insight to the topic. I felt this built speaking and listening skills as well as required students to re-enter the text. […] Commentary from each group was strong, including groups who hypothesized on why Amir felt like a tourist in Afghanistan and why Baba never told Amir about Hassan. This style of conversation worked so well for the group that I am hoping to try it again soon. I heard from more than twelve of the eighteen students in class that day.”

This carried through to A Streetcar Named Desire, too. Check out that Portrait Overview.