While editing our team’s document, “The Twentieth epistle of Horace to his book, modernized by the author of Female conduct, and applied to his own book,” I was expecting to read mostly about how females should behave. Instead, I was shocked to find that the author spent the whole article defending his writing against critics. His defense of his own writing and unusual style of the preface helped me gain a deeper understanding of how important reputation and masculinity were for male writers in the eighteenth century.

Reputation was everything in the eighteenth century. If someone did not have a good reputation, they were seen as less than other men, and could even be viewed as having undesirable female characteristics, “As a result of these caveats and observations, changing notions of honor and civility have added several layers of complexity to the story of an incredibly sharply defined set of masculine identities” (English Masculinities, 15). To criticize a man’s reputation was to question how masculine he was, a cruel insult in an era of strict gender roles. This is captured in action in Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s poem, “The Reasons that Induced Dr. S to write a Poem call’d the Lady’s Dressing room,” Lady Montagu destroyed Jonathan Swift by discrediting his reputation as an honorable man. She knew that insinuating that Swift went to a prostitute and had sexual troubles was the best revenge there could be.

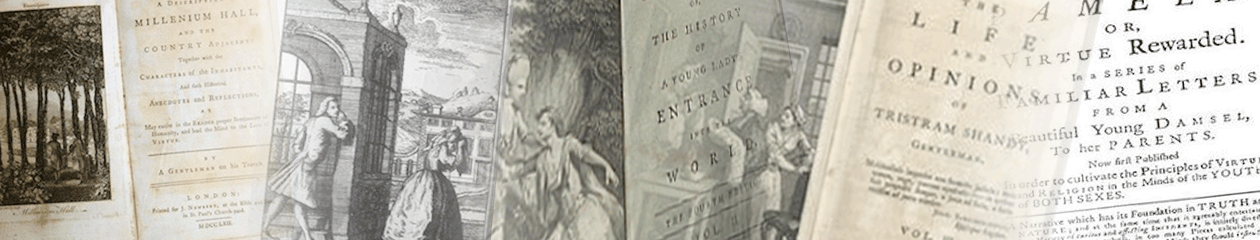

As we’ve learned in class, the title and preface often reveal a lot about how the author wants his audience to read the text. In “The Twentieth epistle of Horace,” the preface captures how delicate male reputations were in the eighteenth century. Under the title are the words “Intended as an Answer to the Remarks on his Book, made by the Writer of the Critical Review, and by the Writer of the Monthly Review” (1). Instead of using this introduction to focus on the idea of a conduct book, the author chooses to let the audience know that he’s focusing instead on the criticism he’s received and to protect his reputation from further insult. While the insults his critics use against him are never directly stated, this aggressive defense of his reputation could likely stem from his masculinity being questioned after writing a female conduct novel (Female Conduct, .the third edition). As Hitchcock points out in English Masculinities 1660-1800, women were viewed as both physically and mentally weaker than men, so being compared to one would be the ultimate insult to an author, “The implications of this transition are usually taken to mean that ‘woman’ was constructed in difference from ‘man’, not only sexually passive but physically weaker than men and because of the presumed homology between body and mind, mentally weaker as well” (8). Accusing a man of acting in a feminine manner is to insult his mind, his body, and his sexual history, three things eighteenth century men value highly.

The structure of the piece is very different from what we’ve seen in previous eighteenth-century texts. Instead of the traditional linear form we’ve seen in novels and essays, the author continues to go back to what he states in the introduction. There is very little content that relates to the actual topic of the piece, which are instructions for how women should behave. Each time it seems as if he is going to begin talking about proper etiquette for ladies, he returns to what he says in the introduction. In other texts, the preface is used by the author as a disclaimer to mold the way the readers read the book. For example, the preface in Roxana tells the readers that if they see anything improper in the text, it’s the dirty mind of the reader and not the fault of the writer, “And all without raising a single idea throughout the whole, that shall shock the exacts purity, even in the warmest of those instances where Purity would be most apprehensible” (31). This way, the writer frees himself from any criticism by assuring the audience that it was written with good intentions. He then continues with the novel without restating the thesis as obviously. The author of The Twentieth epistle takes a different route, and instead spends the entire text referring back to his preface. Even halfway through the novel, he continues to refer back to his preface, “By this we see, how detestable and contemptible these two Roman Scriblers had rendered themselves to all Men of Candor and Genius, by their arrogance” (17). This intense focus on the preface shows how desperate the author is to restore his reputation and reclaim his masculinity.

Editing “The Twentieth epistle of Horace to his book, modernized by the author of Female conduct, and applied to his own book” helped me understand how different the writing style and structure was in the eighteenth century compared to today, but the most important thing I took from this document was an understanding of how a man’s masculinity depended heavily on his reputation, and that honor was so important that they would rather defend their honor than write about the subject of their book.

Bibliography

Hitchcock, T. “English Masculinities.” (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 26 Apr. 2016.

Marriott, T. “The Twentieth Epistle of Horace to His Book, Modernized by the Author of Female Conduct, and Applied to His Own Book. And Intended as an Answer to the Remarks on His Book, Made by the Writer of the Critical Review, and by the Writer of the Monthly Review.” (35) Published by W. Owen, at Homer’s Head, near Temple-Bar, 1759.