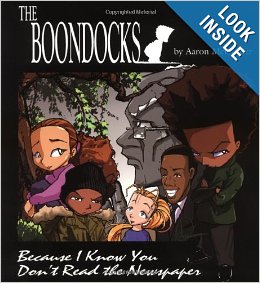

Jazmine Dubois

Character: Jazmine Dubois

Source Text: McGruder, Aaron. Boondocks: Because I Know You Don’t Read Yhe Newspaper

Entry Author: David Lwamugira

Aaron McGruder’s highly intelligent and racially charged comic strip, the Boondocks, provides readers some insight into the thinking of a pair of African American youths named, Huey and Riley, who must navigate their way through a mostly white society. The neighbor of these characters , Jazmine, acts a literal bridge between the two worlds because she has a black father and a white mother. During Jazmine’s first interaction with Huey, Huey tells her, much to her despair, that “it’s good to have more black people around.” Jazmine disputes the fact she is black and asks Huey why he would assume what race she was. Huey responds by saying, “Well first of all, Mariah, your afro is bigger than mine.” When she responds with, “I don’t have an afro – my hair is just a little frizzy today,” Huey retorts: “Angela Davis’ hair was ‘a little frizzy.’ you have an afro.” Jazmine then screams in protest, “I DO NOT and who is Angela Davis?” Huey compares Jazmine to Angela Davis, an African American political activist who took part in the Civil Rights movement and she fails to catch the reference. This shows that Jazmine has the physical appearance of an African American but does not fully identify herself as a member of the community, as well as the gap in historical knowledge between Huey, an African American, and Jazmine, a member of both the White and African American communities.

Jazmine’s identity is constantly being determined by others. When asked by a school questionnaire what race or ethnicity Jazmine belongs to, Jazmine leaves the field blank. The elementary school principal calls Jazmine’s mother in order to get a straight answer and she says it’s up to Jazmine to construct her own identity: “We don’t want anyone doing that for her. Is that clear? If she must be called anything, use the term ‘multiracial.’ Never ‘white,’ never ‘black.’ Ok?” Immediately after this speech, the principal decides to ignore her mother’s advice and identify Jazmine as an African American. So many people in this world ignore the fact Jazmine is a mixture of races. By defining her as one or the other, they limit her growth as a person.

In a moment of desperation, Jazmine expresses her feelings in a very open and honest manner that captures the experience of being biracial:Most people don’t understand what its like being different. Like…I once saw a yellow flower right in the middle of a bunch of red roses…everything around it was either green or red, and here was this yellow flower. It looked lonely. That’s what it’s like being biracial. I’m different from everyone else. My mom and dad say that makes me special, but i just think it’s lonely. (McGruder 27)

Her soliloquy shows the reader she is just a young girl trying to find acceptance in a world where defining someone’s race can still mean defining their character. Jazmine wants to live her life free of judgment or the pressure to choose which race she shall identify with. Yet the notion of belonging to one race or another matters much more to her peers than it does to her. Like any human being, Jazmine wants to be treated with decency and respect.

Roxana

Character: Roxana

Source Text: Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson and those Extraordinary Twins (1894)

Entry Author:

Roxana is a slave woman. Over many years of racial mixing in her ancestry, she no

longer appears black, the 1/16 portion remaining no longer expressing itself. To

outside observers she is white, “of majestic form and stature, her attitudes were

imposing and statuesque, and her gestures and movements distinguished by a noble

and stately grace.”(9) It is interesting to note that her white skin allows her the

agency to switch her children, an act that would denied to a black skinned black

person. Black skinned characters do not appear to have the ability to exercise

agency in any meaningful way of their own. It is only when she is heard speaking

that those who do not know her understand that she is a slave and is black. She

considers herself to be black as well, and does not find that particularly odd. She is a

nurse maid to the children of Mr. Driscoll, as well as having a child herself. She

switches her child with the child of the Driscoll’s so that he may grow up to be a free

man. Other slaves around her recognize her to be a black person. They react to her

easily as a member of their community. (9) Although Roxy is unable to pass for white

because of her speech habits, which mark her as a member of the slave caste, she

recognizes that because her master is unable to distinguish between the two

children, that she would be able to free her son from a lifetime of bondage by

exchanging him with the son of her master. This demonstrates that Roxana

understands that race is only skin deep. She doesn’t see a reason that her son

couldn’t take the place of a white boy if he looks the same. The conventions of black

inferiority do not seem to have worked themselves into her head completely. If she is

able to switch the roles of her children by switching their places, they should be able

to function in their new positions well. Unfortunately this belief that the character of

whites and blacks is fundamentally the same is untrue for her, and her child behaves

very poorly. But this is not because he is black, but because he is a product of his

environment. Like Roxy, who is white in appearance but raised and acts black, her

child raised as a spoiled white boy acts like one. Roxy is unable to take great

measures to enact her own freedom, like running for her life, she does find a way to

reclaim some power through the exchange of her child. Ultimately, Roxana

demonstrates that the character of a person is determined by their upbringing and

social status, not by the genes which they carry. Although the nature and nurture

debate is cast into a strange new realm today, where genetics are beginning to be

found to be responsible for some elements of a persons behavior, at least

pathologically, Roxana is a representative of a train of though which states that all

human behavior is rooted in nurture.

The Sheep Man

Character: The Sheep Man

Source Text: Murakami, Haruki. A Wild Sheep Chase. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1989. Print.

Entry Author: Mike Steigman

A WILD SHEEP CHASE

The Sheep Man is believed to be part sheep and part human, he appears out of the blue as an apparition to the main character searching for his friend in the mountains north of the Junitaki township. Interestingly, his mixed identity is quite literally all he has to his name. The “sheep” in “Sheep Man” comes before “man” insinuating he is more animal-like than human. Upon his entrance, Murakami states, “The Sheep Man wore a full sheepskin pulled over his head. The arms and legs were fake and patched on, but his stocky body fit the costume perfectly. The hood was also fake, but the two horned that curled from his crown were absolutely real (251).

He loses his temper with the main character after being questioned too much, but quickly regains his composure. The sheep man then apologizes to the main character because “sometimes it’s like the sheep in him and the human in him are at odds so he gets like that” (254).

He speaks human language, yet all of his sentences in the narrative are void of any spaces or capitalization, so it’s difficult to distinguish one word from another. One can say his words sound like animal noises in this sense. His basic qualities are reminiscent of a Neanderthal. He is attentive to polite behavior, yet flees at the first sign of violence, even metaphorical like when the protagonist raises his voice. The main character goes further to say, “The sheep man was just like an animal. Approach him and he’d retreat, move away and he’d come closer. As long as I wasn’t going anywhere, there was no hurry” (254). By being part-animal, the Sheep Man is unable to form any emotional ties with the protagonist, therefore further isolating both the main character as well as himself.

Murakami deliberately chooses to blend this man with a sheep in order to extract some of his humanity and highlight his weaknesses. The Sheep Man reveals the reason he hides out in the wilderness is because he didn’t want to go off to war, because members of the Junitaki Township went off to fight in the Russo-Japanese war. He claims he didn’t know who he would be fighting, he just knows he didn’t want to go. And “that’s why he’s a sheep.”

However, there’s a distinct binary evident in partially being a sheep. Sheep are herded by one person, with all their choices made for them by the shepherd. Once divided from the flock, a sheep is left with little direction. Animals are also typically perceived as strong, unstable, wild creatures. Centaurs and lycanthropes, part human and part animal, are mystical creatures, wise and fierce beyond human capabilities. Murakami plays with this notion while simultaneously categorizing, in his name, a mixed-race/species character, arguing that a double identity can weaken one’s abilities just as it can fortify them.

Lastly, The Sheep Man tells the protagonist, who had originally traveled to the Junitaki Township with his girlfriend had forced her to return to the Dolphin Hotel. He assures the protagonist that she didn’t want to be there and she doesn’t belong. The Sheep Man disappears as quickly as he entered in the novel, without explanation.

DANCE, DANCE, DANCE

The Sheep Man reappears in this novel, along with the main character. His mask has become grungy, his horns dilapidated, and he looks significantly older. This time, the Sheep Man appears where he had supposedly sent the main character’s girlfriend in A Wild Sheep Chase, the Dolphin Hotel. The main character presses a button in the elevator, and suddenly it opens its doors on a floor, pitch-black. The elevator refuses to move, so the main character exits to the floor and finds The Sheep Man sitting behind a desk. The Sheep Man speaks in the second person, constantly asking the narrator to tell “us” what’s going on outside as “we” want to know.

The Sheep Man’s costume appears more dingy than “last time”, his stature shorter and his breathing heavier. He advises the main character that he has to dance and keep on dancing, that is the only way to not lose direction.

Toward the end of the novel, the main character visits The Sheep Man together with Yumiyoshi, his girlfriend, but The Sheep Man has vanished. Reminiscent of A Wild Sheep Chase, The Sheep Man appears unable to exist alongside a partner of the protagonist. All that remains are clippings and yellowing pages about sheep that The Sheep Man had been guarding. They are now abandoned with no one to care for them. Having lived away from war and civilization, The Sheep Man grows older and older until he disappears into irrelevance, with any hope of peace from future wars disappearing along with him.

Tom Driscoll (Valet de Chambre)

Character: Tom Driscoll (Valet de Chambre)

Source Text: Mark Twain, The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894)

Entry Author: Adam Kelley

The character known throughout the text of Puddn’head Wilson as Tom Driscoll, a white southern aristocrat, was actually born Valet de Chambre, a mixed race child born a slave, but was switched at birth by his slave mother Roxana, “Roxy”. Chambers, hereafter referred to as Tom, ‘passes’ as the son of Judge Driscoll, descended from the “First Families” of aristocratic “Old Virginia” lineage. Tom’s real identity is later revealed using forensic evidence that proves his birth, but his appearance and success as an imposter challenge 19th century notions of racial identity. Tom, is born a ‘black’ slave by the ‘one drop’ rule, lives half his life as free white man of a locally respected family, and is ultimately revealed and sold back into slavery. The irony of his fate draws out the arbitrary nature of socially and legally constructed racial identity.

The imposter Tom’s race is known through his mixed race mother Roxy. The narrator describes her as “white as anybody, but the one sixteenth of her which was black out voted the other fifteen parts and made her a negro” (Twain 9). Twain’s matter-of-fact tone parodies the absurd nature of 19th century legal definitions of race. He presses this point farther when he describes of Roxy’s son that “he was thirty-one parts white, and he, too, was a slave, and by a fiction of law and custom a negro” (9). Both Roxy’s and her child’s racial status is defined legally in terms of the “one drop rule” that defines them as slaves by descent.

Physically, Roxy’s son ‘Chambers’ and the child Tom Driscoll appear identical. Twain describes of Chambers that “he had blue eyes and flaxen curls, like his white comrade” (9). The only discernable marker between the two infants is their clothing: the Driscoll child dressed in the finest garb and ornament, and Chambers stuffed into a “course” shirt that “barely reached his knees” (9). This further links the racial identity of the children to social cues imbedded in status symbols, and not in anything inherent in the children themselves.

Later in life the imposter Tom is informed by his mother that he was switched at birth and this has a devastating effect on his sense of self. After the revelation he wakes in the morning to exclaim the infamous lines “‘A nigger!—I am a nigger!—oh, I wish I was dead!’” (48). Profoundly disturbed by the news of his origin, Tom’s personality is shattered and he immediately begins to internalize the racial stereotypes he once cast on others. He feels “the curse of Ham upon him” (49) and “the ‘nigger’ in him was ashamed to sit at the white folks table” (49). He becomes deeply aware of his vulnerability under the law, and lives his life in constant fear of being found out.

All of Tom’s social relationships become inverted: his mother, once his slave, now lords her secret knowledge of his identity over him, and his perception of his relationship to his Uncle and his community alters drastically from entitlement to suspicion. His drastic shift in mood draws out the effects of racial prejudice on the marginalized of society. Tom is unwittingly forced into the position of ‘passing’ as white, and grows up oblivious of his origin. But, once he learns his true origin, he immediately begins to question his own identity and alters his personality and behavior. Nevertheless, Tom is consistently a despicable character: callous, cruel, and manipulative, but his punishment of being “sold down the river” feels unjust even for such an unlikable person. Tom, although being guilty of multiple counts of theft and even a murder, is ultimately punished merely for being a fraction ‘negro’.

Armand Aubigny

Source Text: Chopin, Kate. The Awakening: With a Selection of Short Stories. 1899. Reprint. New York City: Bantam Dell, 1981. 177-182. Print.

Entry Author: Emma Baker

In Kate Chopin’s short story, “Desiree’s Baby,” Armand Aubigny is the father of the titular child and the husband of Desiree. Belonging to a well-known, respectable Creole family, he owns a plantation called L’Abri that he inherited from his father. He spent his childhood in Paris until his mother’s death, and returned home to the United States with his father. Presumably, he lived with his mother when she was still alive. His role in the short story focuses on falling in love with Desiree, the adopted daughter of the Valmondés, another well-known creole family. Although Desiree comes from an ‘obscure origin,’ as the Valmondés found her around the ‘toddling age’ near the gateway to their home, Armand initially finds that no obstacle to marriage instead asserting, “What did it matter about a name when he could give her one of the oldest and proudest in Louisiana?” However, while his father treated the slaves under his ownership with kindness, “Young Aubigny’s rule was a strict one, too, and under it his negroes had forgotten how to be gay.” (Chopin, 177)

As such, Chopin positions Armand Aubigny as the character with the most power in his societal context. He is male, wealthy, and at the start of the story, both the reader and the surrounding characters believe he is white. One can see evidence of his exercise of this power in the treatment of his slaves as well as evidence of prejudice and racism. He seems reasonable in his acceptance of a nameless wife whose origins are unknown at the start of the novel, but after the birth of their child one perceives changes in his behavior. Others notice the child’s skin tone before he does but he begins to absent “himself from home; and when there, avoided [Desiree’s] presence and that of her child, without excuse.” (Chopin, 179) After Desiree herself realizes the similarity to one of the quadroon boys of La Blanche, a mulatto slave, she pleads with Armand to tell her what it means. He only responds, “it means…that the child is not white; it means that you are not white.” (Chopin, 180) Armand is not suspected to be the reason for the child’s quadroon appearance, as Desiree’s origin is unknown. As she attempts to defend herself by naming her features, he cruelly responds, “As white as La Blanche,” (Chopin, 180) demonstrating that the physical appearance of whiteness holds no power when one carries ‘black blood.’ Following this, he draws further away from his wife, begins to treat his slaves with a greater cruelty than before and does not prevent his wife from walking unprotected into the bayou with her child never to return. His position in a place of power demonstrates how influential his actions and decisions are on the lives of others around him, as well as highlight the discrepancy between an unknown origin or namelessness and the possibility of having black ancestry.

Chopin does not reveal his parentage until the last lines of the story. As he burns all of Desiree’s belongings he finds a letter sent from his mother to his father saying, “I thank the good God for having so arranged our lives that our dear Armand will never know that his mother, who adores him, belongs to the race that is cursed with the brand of slavery.” (Chopin, 182) The reader then retroactively remembers various mentions throughout the story of “Armand’s dark, handsome face,” (Chopin, 179) and when Desiree pleads, “look at my hand; whiter than yours, Armand.” (Chopin, 180) As such, Chopin constructs Armand as a mixed race character who passes for white and maintains, if not enforces, the status quo in order to demonstrate the hypocrisy of the Louisiana culture. In the revelation of his mixed race as the final and pivotal plot-point, Chopin upsets the status quo by suggesting a complete lack of adherence throughout the piece, as well as emphasizing the dire consequences that resulted from adherence to those conventions.

Lila Mae Watson

Source Text: Whitehead, Colson. The Intuitionist. New York: Anchor Books, 2000. Print.

Entry Author: James Tyler

It is unclear at the outset as to whether Lila Mae Watson is half-black, or as to whether her skin tone enables her to obtain a greater form of acceptance from her white colleagues, or to “pass.” Colson Whitehead chooses to focus marginally on Lila Mae’s relations with her father, who was black and who taught her “white folks can turn on you any minute,” but little mention is made of her mother (Whitehead 23). Although it is made clear that they occupied the same house, when Lila Mae recalls her elevator repairman father showing her and her mother his uniform, it is never made clear as to whether her mother might have been half-black. Aesthetically, Lila Mae exemplifies a “mixed-race” paradigm by her acceptance within a political minority, “the Intuitionists.” Within this political minority, she holds the unique and isolated status as the only black woman “Intuitionist.”

Watson finds herself within a racial identity equation of James Fulton and Pompey, both African American characters who choose to “pass” within white society, although Fulton’s identity is not made clear until well into the novel’s climax. As such, Lila Mae leads a lonely existence in the dark, with few African American role models other than Pompey, who is a conformist, and who appeases the white community, because success as an elevator inspector will ensure a better life for his family. Lila Mae is more determined and more of an individual, even if she has the capacity to be self-centered. She remains focused in the face of obstacles, and openly questions her culpability in the failed elevator inspection, rightfully insistent that there is something more to this situation and embarking on a “quest” to uncover the details in relation to the accident, and, in effect, finds herself discovering more about her own racial identity in the process. Effectively, Colson Whitehead inserts Lila Mae within the context of one of the oldest literary traditions, the “Quest” narrative, a narrative also ascribed to Danny in Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat and Lila Mae’s literary ancestor, Janie Mae Crawford, in Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

On this “quest,” Lila Mae is undeterred and un-intimidated when thugs invade her apartment, when she uncovers the deception of Natchez’s, and certainly when Chancre’s cohorts kidnap her. Still, Watson is compliant to a degree. She calmly accepts her Inspectors Academy room, a converted janitor’s closet. She is excruciatingly polite, even when under pressure, and she dresses conservatively and neatly, clearly invested in not doing anything to offend the sensibilities of a predominately white environment, and fully aware of the significance of her role as a black woman elevator inspector. Like Conrad’s Jewel in Lord Jim, Lila Mae is objectified by those around her; but while Jewel is objectified in a conventional sense, Lila Mae is utilized shamelessly by the Intuitionists for political gain, as proof of their diverse credentials, in contrast with the more conservative Empiricists. Lila Mae is an invaluable political tool as the only female, black elevator inspector, who just happens to be an Intuitionist. As such, whether or not she is willing to admit it or assume kinship with Pompey, she, in effect, is “passing” to a degree, as well.This is where her resemblance to James Fulton, the figurative father of Intuitionism, is most crucial. Both Lila Mae and James Fulton emerge as essential to the novel’s message, and are intrinsically linked to the novel’s theme of social advancement in the context of identity politics. Both hail from a period in which the only African Americans allowed in the department store were employees, although Fulton had more direct experience. James Fulton, a light-skinned black man, plagued by the necessity of “passing” racially, singles out Lila Mae Watson out in his private journals for a significant role within the Intuitionists. This leads one to wonder exactly to what degree he empathized with Lila Mae Watson. “He notices he has written Lila Mae is the one in the margins of his notebook,” Whitehead writes. “That’s right… She doesn’t know what she’s in for, he thinks, dismissing her from his mind” (Whitehead 253).

Hiro Protagonist

Source Text: Stephenson, Neal. Snow Crash. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print.

Entry Author: Erin O’Kelly

While his ability to deal with the plot twists leading up to the final showdown is not predicated on his race, the course of the story makes several turns that do rely on racially charged events to get from plot point A to plot point B to plot point Z.Hiro’s role in the novel covers everything from gathering information to protecting himself and others to chopping people up with swords and, interestingly, his mixed heritage makes subtle but important contributions in all of those areas. He uses his heritage as an American Black to make get the social results he wants in some situations, like when he forces a confrontation with a Japanese pop star to make sure that a concert he organized goes on as planned: “What the hell. This is America, Hiro is American, and there’s no reason to take this politeness thing to an unhealthy extreme” (Stephenson 132). Similarly, in the novel’s world of racially-specific closed-gate communities, a type of franchise called “burbclaves”, his Korean ancestry gives him an in to the city-franchise Mr. Lee’s Greater Hong Kong. Without that access to the refuge of a Greater Hong Kong that his citizenship affords him, he and one of the other main characters, YT, would have likely been taken out of commission in the first hundred pages by a bunch of angry taxi drivers; later on, his ability to access the Asian-centric franchise saves him from getting shot by a bunch of Russian gunmen. His ability to bring YT into this otherwise off-limits sphere of influence also advances the plot by setting the stage for a later karmatic payback for an act of kindness performed during her stay.

The attention his mixed heritage attracts is not entirely benign, however, and also singles him out as a target for curiosity and animosity. Many people are unable to peg his ethnic background, and others’ misinterpretations spark conflict. One Japanese businessman who thinks his black heritage should deny him the use of his inherited Japanese swords challenges his honor and right to hold the weapons (Stephenson 85). A later scene makes him a target for racists who aren’t sure what his heritage is, exactly, but know they don’t like it and can’t figure out which epithet to call him (Stephenson 301). Despite this, a majority of the attention paid to Hiro’s heritage is narrative, not part of any dialogue. Although the reader is up-to-date on the matter, Hiro doesn’t usually bother to correct the person doing the mislabeling. He simply continues doing what he always does: making effective uses of both sides of his heritage to accomplish what he wants or needs to do, and saving a good chunk of the world in the process.

Golden Gray (2nd exhibit)

Source Text: Morrison, Toni. Jazz. New York: Vintage International, 2004.

Entry Author:

Superficial aspects of his appearance create a thin veil hiding his identity. His mother would have regretted him just as she did her affair and given him away if not for his “golden” aspect.

“When [they] bathed him they sometimes passed anxious looks at the palms of his hand, the texture of his drying hair. … True Belle just smiled, and now he knew what she was smiling about, the nigger. But so was he. He had always thought there was only one kind – True Belle’s kind. Black and nothing. Like Henry LesTroy. Like the filthy woman snoring on the cot. But there was another kind – like himself,” (149).

When Gray confronts his father, he seems to project on him all the anxieties and the cognitive dissonance and desires that his newfound knowledge burdens him with. Lestroy narrows in on his fears and confronts him by saying, “‘I know what you came for. To see how black I was. You thought you was white, didn’t you?’” Lestroy offers him ways to be comfortable with his identity and Gray retorts, “’I don’t want to be a free nigger; I want to be a free man.’” He is sensitive to the psychological impact of the categorization even though the reality is the same for him. Lestroy replies, “‘Be what you want – white or black. Choose. But if you choose black, you got to act black, meaning draw your manhood up – quicklike, and don’t bring me no whiteboy sass,’” (173).

Morrison takes care to note that Gray’s torn identity comes not only from the mix of his race alone, but from the way it locates him in between classes and races, making his full membership/authenticity in either group contested.

“What was I thinking of? How could I have imagined him so poorly? Not noticed the hurt that was not linked to the color of his skin, or the blood that beat beneath it. But to some other thing that longed for authenticity, for a right to be in this place, effortlessly without needing to acquire a false face, a laughless grin, a talking posture,” (160).

The reality is that he can choose which race he performs, but the knowledge of his parentage has made him confront the reality that race is a performance. Gray’s crisis results from having become a self-conscious actor in this broadened playing field of racial identity. Being aware of his choice and the fiction of race, but still afloat in the world of identity politics, he no longer feels naturalized in the choice of either identity.

Georges

Character: Georges

Character: Georges

Source Text: Séjour, Victor. “The Mulatto.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. Ed. Henry L. Gates Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. Second ed. N.p.: Penguin Classics, 2003. Print.

Entry Author: Crystal Carpenter

The tragic mulatto/a is normally characterized as a mixed-race figure who finds him- or herself depressed, suicidal, fratricidal, and/or patricidal due either to a lack of identity or to an innate, biological corruption. According to the stereotype, these individuals do not know whether they fit into white society or into black society and are often made to choose between their dual identities, passing either into whiteness (the most familiar trope) or into blackness (Daut 2).

The tragic mulatto, based on gender, is depicted differently. Both have similar aspects but men usually have an oedipal complex. The plot for a male tragic mulatto usually goes through a pattern of identity confliction, loss, power reversal, revenge and rebellion (and sometimes death). Georges use his revenge on Alfred as a way to reverse Alfred’s power over him, and rebelling against his father in an emblematic way. Any slave born out of “the violation of identity caused by miscegenation” (Daut 12) becomes more intense in their revenge and need to kill – as a way to sever the ties between the absent father. Once Georges has reversed the power roles and now holds Alfred’s fate in his grasp, he will seek justice for his mother, wife, and himself by making Alfred the victim. After Georges has discovered that Alfred is his father he commits his final act as the tragic mulatto, taking his own life. Georges as the tragic mulatto stirs mixed emotions within the reader, because his fictional story as a mixed race slave becomes real to the reader. The motivation of his actions was not to kill for the sake of it, but to right the wrong Alfred would not. If Georges had known Alfred was his father he would not have killed him so readily. This is what makes Georges so tragic he became entwined in a false identity of passionate revenge, and never had the chance to mend his own identity.

Work Cited

Daut, Marlene L. “”Sons of White Fathers”: Mulatto Vengeance and the Haitian Revolution in

Victor Séjour’s “The Mulatto”.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 65.1 (2010): 1-37. JSTOR.

Web. 8 Nov. 2013.

Squeak/Mary Agnes

Character: Squeak/Mary Agnes

Character: Squeak/Mary Agnes

Source Text: Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. The United States of America: Harcourt, 1982. Print.

Entry Author: Claire Tierney

Squeak’s character is shaped largely by her relativity to the other women in the novel. Readers are introduced to her as Harpo’s new girl, where she is slightly villainized as she is seen as Sophia’s replacement. This is evidenced when Squeak’s teeth are knocked out by Sophia during a confrontation. By the end of the novel, Mary Agnes’s character is as dependable and competent as any of the other female characters, and this forces the characters and readers to respect her. This transformation and this sense of separation from the other characters is evident in her song,

They calls me yellow,

like yellow be my name

They calls me yellow

like yellow be my name

But if yellow is a name

Why ain’t black the same

Well, if I say hey black girl

Lord, she try to ruin my game

(99).

Squeak stands strong with the other women in the novel, while also claiming her own independence and identity as a woman of mixed race, as an outsider looking in. This separateness becomes a point of independence for Mary Agnes. At the novel’s beginning Squeak is an outsider in her world. She stood pale in comparison to strong characters like Shug and Sophia. By the end of the novel, she proves that she is not to be compared to other women, that she stands alone.