Danny Lopez

Character: Danny Lopez

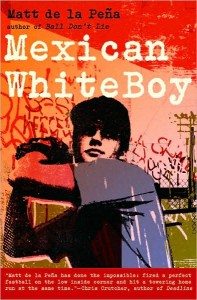

Source Text: De La Pena, Matt. Mexican White Boy. New York: Delacorte Press, 2008. Print.

Entry Author: James Tyler

Sixteen-year-old Danny Lopez is half-Mexican and lives in comfortable San Diego county; the son of a white mother and an absent father, who walked out on the family when he was a child. Confused over the concept of his own identity, he wonders why his father left the family for Mexico and whether the motivation involved embarrassment over having a biracial son. The novel follows Danny’s experiences on a visit to National City, Mexico, in search of his biological father in Ensenada.

The only other Hispanics Danny has any familiarity with are Mexican people who “do under-the-table yard work and hide out in the hills because they’re in San Diego illegally” (De La Pena, 2). As much as Danny feels like an outsider being a biracial American in San Diego, he feels equally out of sorts in National City, if not more, because he is not fluent in the Spanish language. And, what’s more, not only is he described as “a shade darker than all the white kids at his private school,” but whenever he comes to National City, “where his dad grew up, where all his aunts and uncles and cousins still live – he feels pale. A full shade lighter. Albino almost” (De La Pena, 3).

Hispanics/Latinos are the fastest growing minority within the United States and are expected to constitute a sound majority within several generations, so much so that political scientists have labeled the demographic, “the sleeping giant.” As such, it is almost impossible to define such a demographically diverse population within one subgroup. Class, Nationality, Ethnicity, Biological Race, Politics, and Culture/Language all factor into the definition of what it means to be a Hispanic/Latino. As such, the identity crisis experience by Danny is not at all surprising or unusual.

The literary device De La Pena employs which symbolically unites such a diverse group is Basebal. A skilled pitcher, Danny has a proportionately difficult time succeeding in his favorite sport, as much as he has trouble straightening out his identity conflict, because despite his talent, he is cut from the Baseball team over his lack of focus. But, his first moment of true belonging in Mexico comes while observing the Mexican kids playing Baseball. “He’d give anything to be out there playing instead of standing here watching,” De La Pena writes. “Nobody plays stickball in Leucadia. Why don’t the white kids play stickball? He wonders. Maybe because they have real baseball fields…Or maybe they’ve just never thought of it.” This moment is also how he comes into contact with his first close Mexican friend, the half-black “negrito,” Uno, even if his first contact with Uno is by getting knocked out.

As a Hispanic-American who was raised in a predominantly white suburban environment, the individual obstacles presented to Danny Lopez, in terms of identity exploration, were so readily identifiable to me that at times it was frightening. De La Pena very well could have gone the traditional route of making Danny the stereotypical “angry half-breed” full of a frustration he can only express in brute violence. On the contrary, Danny Lopez is not only a sensitive character, but a startlingly troubled one, who takes his frustration out on himself. From the beginning the near-mute Danny is struggling with a form of Depression, which he copes with by cutting his wrists. While I have never reached this level of emotional depravity, the conveyed feeling of being “between worlds,” due to language barriers, skin color, or class differences, is such a familiar, relatable emotion that someone being led to that form of self-abuse by it is almost unsurprising to me. With any luck, novels such as this will encourage a greater dialogue and discourse regarding teens with mixed identities and the challenges they face, so that such heartbreaking self-harm will be a thing of the past.