Hugo Ball, Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, 1916. He has nothing to do with Melville’s Civil War poetry. He just kind of became the class mascot after we spent an entire session on the recitation of “Gadji Beri Bimba.”

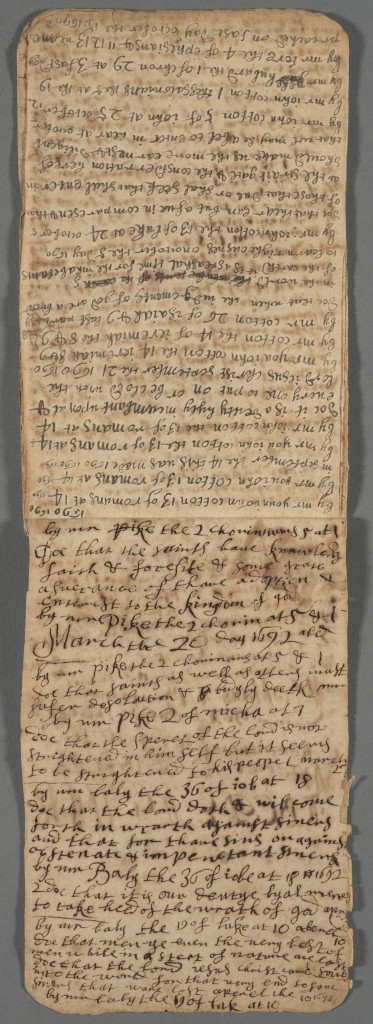

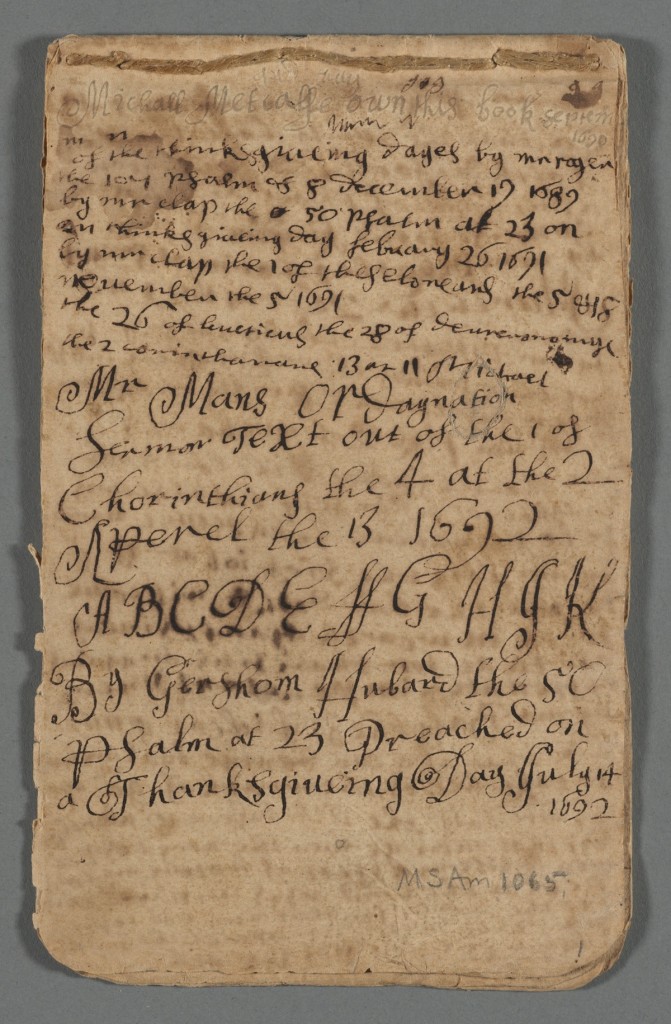

In fall 2012, students in my American Poetry class recorded an audio book of Herman Melville’s civil war poems for LibriVox.org, a wonderful organization that provides free audio books of works in the public domain. Here is just a little information about our project.

The class divided into three recording teams, and each student had at least one designated role in the process. Roles included directors, primary readers, historical dramaturgs, and sound technicians. A single project manager helped to coordinate the work of all three teams.

Each team read through Battle-Pieces and decided which poems they would like to record. Sometimes an individual reader would feel a strong connection and want to read a particular poem. Jon Brien, for example, was eager to kick off the the whole collection with his reading of “The Portent.”

In some cases, an entire team would have a concept for the poem, as in this interpretation of “Donelson,” the only poem in the collection to make use of multiple voices. Their choice works well to convey the many points of view which make up this poem.

In quite a few cases, more than one team wanted a particular poem. We decided to audition competing claimants, and the class as a whole decided which interpretations and which voices best suited some of the most popular poems. Jason DeMartini eventually won the most hotly contested poem in the collection, “The House-top,” but the competition was fierce from Laura Mathew and My Bui (who was kicking it old school, reciting from memory!). We even recorded the “The Battle for Battle-Pieces,” our very own competition reality show:

you gotta fight

for your right

to recite